|

When the phrase "sculpture for the community" is mentioned in Britain we tend to think immediately of the extension of public sculpture in the post war period to municipal housing estates, New Towns and schools, the sort of sculpture which was show-cased at the Festival of Britain in 1951. The messages of national and family solidarity and mutual assistance put across in much of the public sculpture of this period seem to echo the sentiment behind the proposals for social assistance to be found in the Beveridge Report, which Clement Attlee's Labour government set out to implement. For this reason they have recently been christened "Welfare State Monuments". Some of the sculptors contributing to these schemes were British. They include Henry Moore, Robert Clatworthy, Ralph Brown and Sydney Harpley. But Margaret Garlake, who has written much on this subject has stressed the contribution of immigrants from Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia and Hungary. She finds that their background peculiarly suited them to putting over the sort of communitarian messages favoured by the commissioning bodies. She writes, "They brought to bear on their work in England their immersion in a long and flourishing tradition of figurative sculpture, with the result that it retained strong echoes both of their earlier public commissions and of practices that had been centrally concerned with old European themes of the mother and child, the family, of the male body as a signifier of heroism, suffering and survival". My talk can only reinforce her point, firstly by looking back at the world from which some of these sculptors came, and secondly by drawing attention to a significant earlier point of contact, which may have provided a model for the post-War planners.

|

|

I should begin by saying that the dates of my title ought really to have been 1923 to 1960. The date 1930 occurred to me in relation to Arthur Fleischmann's relatively late contribution to the Viennese socialist municipal housing project between the wars. Fleischmann only completed his sculpture studies at the Vienna Academy in 1928, and the first architectural sculpture of his that we are able to date was put up in 1931, at a point only three years before Anton Dollfuss organised the putsch which

brought an end to the socialist regime in Vienna. It is about the housing projects initiated by this regime that I want to talk, and principally from the rather specialist angle of architectural and decorative sculpture. I think that it will be useful, in this context to give an airing to Arthur Fleischmann's recorded works for these projects. Although we have photographs and even reviews of these works, we have not been able to establish where some of them were, let alone whether they still survive today. Possibly the simple process of giving them a showing here may lead to them being tracked down. Then, since several Viennese sculptors of this generation, including Fleischmann, emigrated, either before or after the war, to London, I thought that it might be relevant to look at one almost immediate repercussion of the Viennese initiatives in the London of the interwar period, before the Viennese sculptors arrived. This was a slum-clearance and redevelopment scheme which took place simultaneously with the Viennese experiment, in the area North of Saint Pancras called Somers Town. Part of the inspiration for this came from Vienna, and it shared with the housing estates of the New Vienna the credit for incorporating sculpted decoration into low cost housing. The sculptor Gilbert Bayes who was chiefly responsible for the décor in Somers Town, had his studio in the same part of northern St John's Wood where Arthur and Joy Fleischmann lived, and where Joy still lives. A sort of celebrity guest appearance will be made in this story by Edward Prince of Wales, who was a share-holder in the Saint Pancras House Improvement Society. He visited the Viennese estates just after the socialists were forced out of office, in 1935. Whilst in Vienna he behaved in a way which conflicts with the rather commonly held view that he was Hitler's closest ally in Britain.

|

|

If we are looking for the antecedents of the experiment of bringing sculpture to the people, we may have to go back to England in the 19th century. Clearly the whole phenomenon of art for the people can be traced back to William Morris's socialist arts and crafts vision, but Morris had little time for sculpture as such. The largest exposure of the greatest number to sculpture must have taken place at the international exhibitions, starting with the Great Exhibition of 1851. When relocated to Sydenham, where it opened in 1854, the Crystal Palace took the form of a universal museum. A very large part of the exhibit was made up of sculpture both ancient and modern. Alongside the fine art sculptures were the natural historical models, such as the famous dinosaurs, which were intended more for instruction than aesthetic delight. Elsewhere in the gardens stood mythological and allegorical figures, some of them possessing special relevance, but little adapted to the tastes of the average viewer. The Crystal Palace soon acquired the reputation of being a "Palace of the People", but the implication of this was simply that the average visitor might feel gratified at finding himself in such grand surroundings, with ornaments akin to those adorning a gentleman's park. It was even observed that people were not at ease amongst these things and that they tended to retreat to the restaurants and stuff themselves with food, whilst awaiting the evening's firework display.

|

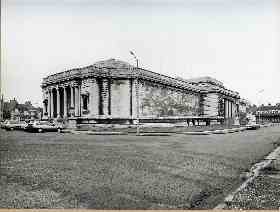

Until the Viennese experiment, which I have to insist was something of a first, the aesthetic element in public housing projects was limited to purely architectural invention. It is generally recognised that the breakthrough into a more comely style of public housing was achieved by the LCC, in its slum clearance projects of the 1890s. The first of these was the Boundary Street Estate, which replaced a particularly frightening and squalid area called the Old Nichol in the western part of Bethnal Green, not far from Shoreditch. On the LCC estates, the oppressive effect of the necessarily very tall blocks was offset by the variety of brick patterns, decorative ironwork, and the charm of some of the entrance porches. These estates are sculpture free. A closer approach to the Viennese example was the provision of art in privately financed garden cities. At Port Sunlight, the Lever family made over its art collection for enjoyment by the community, which consisted of operatives in the Sunlight Soap factory. The collection was housed in a rather grand building on the central avenue of this garden city. It contains quite a lot of sculpture. A monument to First Lord Leverhulme was placed outside the gallery much later, but after World War 1, Port Sunlight got a very large War Memorial, which celebrates family values and the cohesion of the community in the hour of peril. Another turn of the century Garden City, Whiteley Village in Surrey has at its centre, in the style of old almshouses an allegorical memorial commemorating the founder. This memorial was the work of George Frampton, the sculptor whose studio Arthur Fleischmann occupied from 1958 to 1990.

Until the Viennese experiment, which I have to insist was something of a first, the aesthetic element in public housing projects was limited to purely architectural invention. It is generally recognised that the breakthrough into a more comely style of public housing was achieved by the LCC, in its slum clearance projects of the 1890s. The first of these was the Boundary Street Estate, which replaced a particularly frightening and squalid area called the Old Nichol in the western part of Bethnal Green, not far from Shoreditch. On the LCC estates, the oppressive effect of the necessarily very tall blocks was offset by the variety of brick patterns, decorative ironwork, and the charm of some of the entrance porches. These estates are sculpture free. A closer approach to the Viennese example was the provision of art in privately financed garden cities. At Port Sunlight, the Lever family made over its art collection for enjoyment by the community, which consisted of operatives in the Sunlight Soap factory. The collection was housed in a rather grand building on the central avenue of this garden city. It contains quite a lot of sculpture. A monument to First Lord Leverhulme was placed outside the gallery much later, but after World War 1, Port Sunlight got a very large War Memorial, which celebrates family values and the cohesion of the community in the hour of peril. Another turn of the century Garden City, Whiteley Village in Surrey has at its centre, in the style of old almshouses an allegorical memorial commemorating the founder. This memorial was the work of George Frampton, the sculptor whose studio Arthur Fleischmann occupied from 1958 to 1990.

|

Little attention has been given to the interwar experiments with community sculpture. One of the reasons for this is that, after the 2nd World War the main architectural histories excluded the Viennese housing projects from the record. Their monumentalism and failure to exploit modern methods of mass-production consigned them to an artistic limbo. The main advances in the period were seen as having taken place in Berlin, Stuttgart and North West Holland. Under the influence of Bauhaus teaching and De Stijl theory, the German and Dutch estates were characterised by clean-lined functional minimalism. Not only were they devoid of any architectural ornament, but the neighbourhoods were mainly free of sculpture. Amsterdam was the only exception acknowledged in these histories. There, an expressionist brick idiom, originated in the immediate post-War years by the group called Wendingen, continued unabated. This brick architecture was accompanied on major public and commercial building by idiosyncratic, and often bizarre, sculptural features. However, these did not reach the very large housing estates built in the Amsterdam suburbs in this period.

Little attention has been given to the interwar experiments with community sculpture. One of the reasons for this is that, after the 2nd World War the main architectural histories excluded the Viennese housing projects from the record. Their monumentalism and failure to exploit modern methods of mass-production consigned them to an artistic limbo. The main advances in the period were seen as having taken place in Berlin, Stuttgart and North West Holland. Under the influence of Bauhaus teaching and De Stijl theory, the German and Dutch estates were characterised by clean-lined functional minimalism. Not only were they devoid of any architectural ornament, but the neighbourhoods were mainly free of sculpture. Amsterdam was the only exception acknowledged in these histories. There, an expressionist brick idiom, originated in the immediate post-War years by the group called Wendingen, continued unabated. This brick architecture was accompanied on major public and commercial building by idiosyncratic, and often bizarre, sculptural features. However, these did not reach the very large housing estates built in the Amsterdam suburbs in this period.

|

|

|

|

Only in the late 1960s and 1970s, in the prelude to post-modernism did people begin to look again at what had been done in Vienna, in a period which had originally been seen as a trough, a decline from the great standards set by Adolf Loos and Otto Wagner after the turn of the century. Even in the more artistically accommodating climate of 1970, the sculptural adornments of the Viennese estates continued to be overlooked, despite the fact that they had been made much of in the promotional literature of the interwar years. This neglect of the phenomenon in architectural literature does not mean that the social benefits of the schemes went unregarded. Both in England and in America, official bodies concerned with public housing consulted Viennese architects and planners. On the strength of his experience of low-cost housing, the Viennese architect Michael Rosenauer was invited to England in 1927 to advise the LCC and the Ministry of Health on questions of slum-clearance. In the early 1930s, Charles Oscar Hardy was commissioned by the City Institute of Economics in Washington to produce a study of the Viennese housing programme, which appeared in 1934.

|

|

It may seem a bit like taking coals to Newcastle for an English art-historian, whose German has never been very good, to come to Vienna to tell the story of Red Vienna's public housing, but for the benefit of English listeners, I will have to give a brief account. After the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy at the end of the First World War, Austria found itself in dire straits. It had inherited a huge administrative machinery from its time as capital of the Empire, but it was completely cut off from the regions which had once supplied raw materials for industry. Financially crippled and with a colossal unemployment and housing problem, the country was threatened with revolution. This was avoided partly through the activities of the progressivist left-wing group called the Social Democratic Workers Party, which favoured the peaceful path to socialism. This party never enjoyed wide support outside the main cities of Austria, and once the immediate threat of revolution had passed, it fell back on Vienna, the constituency in which it felt most confident, determined to make the city a model of municipal socialism.

|

|

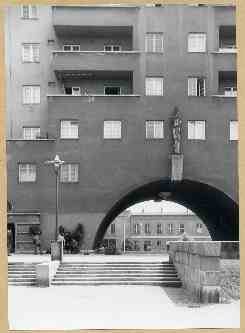

The first socialist mayor of Vienna was elected in May 1919. In 1922 Vienna became a federal province, so that its mayor was also a provincial governor. It was hence able to benefit from both city and national financial support. The new socialist local government inherited a huge housing problem, with large shanty-towns on the periphery. Before it had come to power, some self-help groups, such as the Disabled Veterans Association, and other housing co-operatives had set about building more permanent accommodation, but after 1923 a huge programme was initiated by the Social Democrats. They took a rather different line on re-housing, one for which they were to come in for much criticism. One of the conditions of the acquisition of provincial status was that Vienna's boundaries were fixed, limiting the degree of suburban development. The response to this was to go for high density inner city development. The predominant form this took was the Hof-Haus, a traditional Austrian building type, which can be translated as a perimeter block. This was an almost fortress-like structure, built around a central court or courts, with access through an often gigantic arch. Amongst the 190 architects employed, a large proportion were not municipal employees. Quite a number of them were pupils of Otto Wagner, who had imbibed from him a respect for Viennese city-scape. Nonetheless, the emphasis was on massive powerful forms, occasionally contrasted with jagged angular projections, similar to those found in some of the Czech so-called cubist architecture of the 1920s. Anybody who knows these buildings will be aware that this is a simplified description. The most famous of the estates, the Karl Marx Hof, consists of an asymmetrical series of courts, dominated at its centre by a very high and long central block, punctuated with towers and massive arched openings, overlooking a formal garden.. The flats within these Wohnhäuser were small. They contained no bathrooms. Bathing and laundry facilities were communal. Libraries, shops and kindergartens were included within the larger complexes. In some, paddling pools were provided, which in winter could be converted into skating rinks.

|

|

|

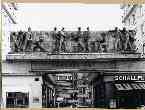

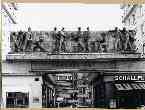

In the promotional literature of the time, it was stated that the approach was designed to be expressive, rather than merely functional, that this was a response to a deep-seated need of the Viennese people for something more than machines for living. A publication put out in 1931 pronounced that "Life is short and art is long. Very soon people will have had enough of functionalism, and the Viennese can congratulate themselves in not having perpetuated it in their home-town". The provision of sculpture and ornament, it was claimed, was a response to this "Schmuckbedürfnis des Wiener Volkes", roughly translatable as the Viennese thirst for ornament. It was also perhaps a bit of a forced concession to the challenge of the historical environment, the need to maintain traditions. The old Vienna had been dominated by the court, the new Vienna was the Vienna of the People. The architecture of the court had often been florid. There was no reason why the people should be given less. So very often it appears merely as punctuation to the architecture, or as a reminiscence of the baroque décor of Old Vienna, as in these romping children at the bottom of the staircases of the Reumannhof, which hark back to the world of Fischer von Erlach and Hildebrand. But occasionally monuments to socialist administrators and martyrs were built into the schemes. Some of the sculpture was clearly designed to amuse the residents, like these images of children from a play area, or Hanna Gärdtner's charming Bear Fountain in the Matteotihof. Something more like earnest social realism begins to appear around 1930, perhaps because the socialist regime felt itself increasingly threatened by the political opposition. This we can see in the very ambitious frieze of heroic workers, executed in ceramic by Siegfried Charoux for the Zürcher-Hof in 1930.

|

|

Now I think we should look at the three works which Arthur Fleischmann contributed to these schemes. The first I am showing you is the only one which we have actually been able to locate. It is the frieze on the Hickelgasse Wohnhaus, which the plaque inside the entrance arch informs us was erected in 1931. It consists of sturdy babies flanked by reclining male and female figures, presumably the parents of the babies, who on one side are conspicuously nude, whilst on the other they are preponderantly draped. Over the doorway and under the projecting oriel, these adult figures are seen tangling with the fruit of the vine, so the frieze should maybe be read from left to right as the progress from innocence to experience, via a period of debauch. In and amongst all this are birds and flowers. The work spans the entire Hickelgasse front above the ground floor windows, and is executed in reddish terracotta. The moral message, if there is one, is easy enough to overlook, and the frieze presents an idyllic contrast to the dusty austerity of the urban scene.

|

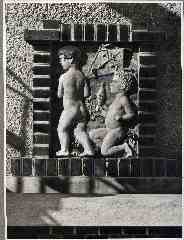

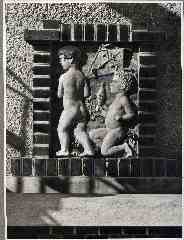

Another series of photographs in the Fleischmann archive are identified in handwritten descriptions on their backs, as representing a Gemeinde Wien bathing establishment, and the name of an architect is given, unfortunately illegibly. The relief panel provided by Arthur Fleischmann is clearly in high toned, coloured terracotta, and represents two naked children, one holding a kite, and the other the ball of kite string. It was one of the chief claims to success of the socialist regime, that it had procured the opportunity for health-giving exercise to a population, which had been suffering all the ill effects of malnutrition and overcrowding during and after the First World War. Bathing and paddling pools were a major feature of this therapeutic programme. The third piece is especially interesting, since it is symbolic of the home-building activities themselves. It is in the form of a triptych, with in one side panel an architect, in the other a bricklayer, and in the centre a monumental group of a mother and two children. The relief is illustrated in Forum, an art periodical of the time. The magazine states that the work symbolizes the genesis of the house, that it was for one of the Wiener Arbeiterhäuser, and goes on to praise Fleischmann's work for the originality of the thought behind it and the clarity of the composition. An article on Fleischmann's work in a later number of Forum, which appeared after the downfall of the socialist local government in Vienna, refers back to the work which Fleischmann had done for the Viennese workers' dwellings. The article mentions the progress which Fleischmann's work had made from the rather cool anatomical accuracy of his earliest pieces, which reflected his training in medicine, towards a greater stylisation. It also pointed out that the architectural sculpture episode had given him the chance to investigate the peculiar qualities of materials, in this case, one imagines, the effect and durability of different sorts of architectural ceramic. The Genesis of the House triptych as we can call it, certainly reflects the tendency to stylisation, with the hieratic gestures of the architect and builder, and the almost geometrical arrangement of the limbs of the central family group.

Another series of photographs in the Fleischmann archive are identified in handwritten descriptions on their backs, as representing a Gemeinde Wien bathing establishment, and the name of an architect is given, unfortunately illegibly. The relief panel provided by Arthur Fleischmann is clearly in high toned, coloured terracotta, and represents two naked children, one holding a kite, and the other the ball of kite string. It was one of the chief claims to success of the socialist regime, that it had procured the opportunity for health-giving exercise to a population, which had been suffering all the ill effects of malnutrition and overcrowding during and after the First World War. Bathing and paddling pools were a major feature of this therapeutic programme. The third piece is especially interesting, since it is symbolic of the home-building activities themselves. It is in the form of a triptych, with in one side panel an architect, in the other a bricklayer, and in the centre a monumental group of a mother and two children. The relief is illustrated in Forum, an art periodical of the time. The magazine states that the work symbolizes the genesis of the house, that it was for one of the Wiener Arbeiterhäuser, and goes on to praise Fleischmann's work for the originality of the thought behind it and the clarity of the composition. An article on Fleischmann's work in a later number of Forum, which appeared after the downfall of the socialist local government in Vienna, refers back to the work which Fleischmann had done for the Viennese workers' dwellings. The article mentions the progress which Fleischmann's work had made from the rather cool anatomical accuracy of his earliest pieces, which reflected his training in medicine, towards a greater stylisation. It also pointed out that the architectural sculpture episode had given him the chance to investigate the peculiar qualities of materials, in this case, one imagines, the effect and durability of different sorts of architectural ceramic. The Genesis of the House triptych as we can call it, certainly reflects the tendency to stylisation, with the hieratic gestures of the architect and builder, and the almost geometrical arrangement of the limbs of the central family group.

|

|

|

Fleischmann's relief may well be a response to an earlier communitarian sculpture. Over the entrance arch of the Siedlung Starchant in Vienna XVI there is a similarly composed relief.. This siedlung was a cottage estate, put up in 1921, before the social democrats' housing project got under way, by a Christian Socialist housing co-operative called "Heim". The relief is in a tripartite panel arrangement, obviously reminiscent of church altarpieces. Since the estate in question is of a more landscaped, garden city type, the side panels appear to contain an architect and a gardener, whilst in the centre are two families flanking a head of Christ and what appears to be a church, but may simply be a stylised house. This estate had a church at its centre, and clearly the provision of spiritual support was seen here as a vital ingredient. Whereas we know that Arthur Fleischmann was already achieving some renown as a sculptor of religious subjects, and that he would later definitely convert to Catholicism, it does look as though, at this stage, he was obliged to submit to the requirements of the municipal government. It is possible that in his triptych he was knowingly twitching the earlier composition to fit the Social Democratic agenda, and giving it, at the same time, a considerably more virile inflection.

|

|

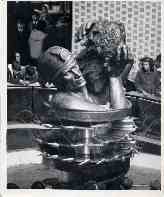

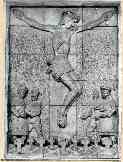

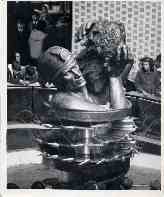

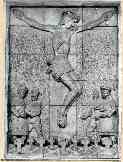

The rather forceful and heroic tone of this triptych relief does reappear in the fountain which Fleischmann designed and modelled for the National Coal Board's offices at Lowton, near Manchester, in 1964, but this particular note is somewhat atypical of his work as a whole. Certainly after his short stay in the island of Bali, a stay whose brevity was in inverse proportion to its long term effect on his artistic imagination, his inclination would be away from such heroics and towards a dreamy or playful sensualism. The secularism of the housing project sculptures could already be contrasted during his Vienna period with the memorial he executed for the Russian church to Austro-Hungarian soldiers who died in captivity during the 1914-18 War. This, as the commentator in Forum wrote, was "no hymn to war, but was intended to promote harmony amongst peoples". A very large crucifix dominates, with an almost byzantine subjectivity of scale, the Austro-Hungarian, Russian, Italian and Serbian soldiers fraternising behind a row of war graves.

|

|

|

The supression of the socialist regime in Vienna in 1934 must have meant that an important source of commissions dried up for sculptors like Arthur Fleischmann. The 1936 Forum article mentions no further major public commissions, and three out of four works illustrating it are intimate portrait studies. The positive recollection of the work on the arbeiterhäuser by the author, Kálmán Brogyányi must reflect Fleischmann's own feelings about the episode. In the immediate aftermath of the war, the American historian Charles Gulick wrote movingly enough of the symbolic charge of what he referred to as the Viennese "city houses". He wrote "The cannons of Austrian fascism brought death and destruction into dwellings destined for life and happiness. But it was in vain. Probably more than anything else the 'city houses' had made the Viennese worker realise that he was not a propertyless stranger in a society that was not his. In looking at their massive contours he experienced the same pride which the medieval baron felt when he looked at the walls of his castle………….In the days when a brutal dictatorship ordered and commanded, when liberty and peace were trodden under foot, the stone witnesses of a ten-year building policy reminded men and women of Vienna of the peaceful forces of democracy which created through the people and for the people. They helped to keep aglow the longing for a freedom which has come again."

|

|

In one of the newsletters of the Saint Pancras Houes Improvement Society, the architect of the society referred to the reciprocal influences between London and Vienna in the interwar period as an inspirational boomerang. People who have written about the Viennese estates have had to take into account their inevitable dependance on what had already gone on in London. The extent of the influence of Vienna's housing projects in London has received rather less attention. Somers Town, the area on which I shall concentrate is not the only example, but it is, as far as I know the most conspicuous. Even the LCC estates in the area, which were also put up in the 1920s and 30s have a strong Viennese inflection to them. From early photographs of the LCC's Ossulston Street housing scheme, one could well believe oneself to be in Vienna. However, the ones that interest me most are those put up by the Saint Pancras House Improvement Society. This was a religiously inspired charitable endeavour, which grew out of the Mission of Magdalen College, Oxford, which was already situated in the area. The Society was set up in 1924 by Father Basil Jellicoe, an Anglo-Catholic priest, who had taken up the post of Magdalen Missioner in 1921. The present-day Saint Pancras and Humanist Housing Association rather plays down the original crusading impulse, but the pre-war editions of the Society's newsletter, Housing Happenings, were a sort of pulpit for Father Jellicoe, who saw slums as the work of the devil, and who was concerned even that the local pubs should be reclaimed, so that there should at last be "room for Him in the inn". Nothing could have been further from the secular spirit of the Viennese project. At any opening of a new block or laying of a foundation stone, a bishop, or even the archbishop was likely to be present to give his blessing. When setting up the society, one of Father Jellicoe's most pressing requirements was to find an architect. The man he came up with was obviously "a gem", the perfect man for the job. His name was Ian Hamilton. Hamilton was evidently extraordinarily committed to the objectives of the society, and at the same time highly astute about planning regulations and the financial aspects of what was at all times an economically-challenged project. Basil Jellicoe's oft-heard rallying cry was "Housing is not enough". For him that meant not only reclaiming slums, but reclaiming the souls of the slum-dwellers, with the slight implication, though he would never have put it like that, that cleanliness is next to godliness. With Ian Hamilton this urge to go beyond the immediate physical requirements took a more artistic form.

|

The society's largest development within the Somers Town area was the Sidney Street Estate, which Hamilton explained was based on the Viennese model, and on recollections of English collegiate buildings and almshouses. In some of the earlier buildings of the society, rather minimal sculpted features had been included; some della Robbia plaques, and a figure of the Virgin on a conspicuous corner of one of the first blocks. The figure of the Virgin was sculpted, we are told, by "the mother of the architect". In drawing up the designs for the Sidney Street estate, Hamilton included a number of features in coloured ceramic modelled by the already well-established sculptor, Gilbert Bayes, and made by the Doulton company. At Sidney Street these consisted of lunettes over the first floor windows, with roundels illustrating Hans Andersen's fairy stories, and washing post finials, many of them based on nursery rhymes. There was also a statue of St. Anthony and his donkey for the St. Anthony block and a relief of the Four Seasons around the clock on the central courtyard. Hamilton hoped that sponsors would come forward for other features, such as an ornamental fountain. To this end the Treasurer of the society set up a fund called "Gardens, Sculpture and Gates", in the hope that these things could be "provided more nobly than the society is able to do from its own resources". This initiative is now recognised to have been a first in Britain, and it must be the model for the policy adopted in the post-War period for LCC estates and New Towns. Although Vienna is much talked about in the society newsletter, it is not mentioned specifically in relation to the sculpture issue, but I do feel that it must have played a part in inspiring this new development. Fairy stories and nursery rhymes were often illustrated in the painted decoration of Vienna's municipal blocks. My view is further supported by the fact that courses in painting, introduced for the benefit of the children on the Somers-Town estate in the early thirties, and intended to develop their powers of creative self-expression, followed principles advocated by a Professor Cizek of Vienna.

The society's largest development within the Somers Town area was the Sidney Street Estate, which Hamilton explained was based on the Viennese model, and on recollections of English collegiate buildings and almshouses. In some of the earlier buildings of the society, rather minimal sculpted features had been included; some della Robbia plaques, and a figure of the Virgin on a conspicuous corner of one of the first blocks. The figure of the Virgin was sculpted, we are told, by "the mother of the architect". In drawing up the designs for the Sidney Street estate, Hamilton included a number of features in coloured ceramic modelled by the already well-established sculptor, Gilbert Bayes, and made by the Doulton company. At Sidney Street these consisted of lunettes over the first floor windows, with roundels illustrating Hans Andersen's fairy stories, and washing post finials, many of them based on nursery rhymes. There was also a statue of St. Anthony and his donkey for the St. Anthony block and a relief of the Four Seasons around the clock on the central courtyard. Hamilton hoped that sponsors would come forward for other features, such as an ornamental fountain. To this end the Treasurer of the society set up a fund called "Gardens, Sculpture and Gates", in the hope that these things could be "provided more nobly than the society is able to do from its own resources". This initiative is now recognised to have been a first in Britain, and it must be the model for the policy adopted in the post-War period for LCC estates and New Towns. Although Vienna is much talked about in the society newsletter, it is not mentioned specifically in relation to the sculpture issue, but I do feel that it must have played a part in inspiring this new development. Fairy stories and nursery rhymes were often illustrated in the painted decoration of Vienna's municipal blocks. My view is further supported by the fact that courses in painting, introduced for the benefit of the children on the Somers-Town estate in the early thirties, and intended to develop their powers of creative self-expression, followed principles advocated by a Professor Cizek of Vienna.

|

|

Vienna's specialists were also the pretext for visits to the city by Edward Prince of Wales in 1935 and 1936. After the second of these visits, his ear specialist, Dr Neumann was able to reassure the readers of The Times that his Majesty's ears were "in the same excellent condition as last year". The Prince of Wales was a shareholder in the Saint Pancras House Improvement Society. He had a general charitable interest in these things, but also probably hoped to learn about urban housing in order to improve his own Duchy of Cornwall Estates. 1935 was the year following the repression of the Viennese socialist local government, and the Prince made something of a stir in Vienna by declining to visit the Rathaus, but making a special request to be taken to the workers' housing about which the world had heard so much. According to the left wing American journalist G.E.R. Gedye, the Prince announced his intentions to his barber at the Hotel Bristol. When the barber expressed surprise, the Prince of Wales answered "Rathaus? - Good God no! What on earth would my workers think of me in London if I went to that place which the Fascists took away from the Socialists?" He was taken to the Karl Marx Hof and the Goethehof. Gedye, who tagged along, claimed that the officials accompanying the Prince mercilessly pumped Heimwehr propaganda into him as he did his rounds. Philip Ziegler, the Prince's official biographer has warned us that we should take Gedye's anecdotes with a pinch of salt, but a letter from a Viennese resident in London to a member of Edward's staff, confirms that "it really made an impression in Vienna when the King visited the workmen's blocks of flats with such interest". This is one of the revealing documents presented by Susan Williams in her recent book, The People's King.

|

This little diversion has in itself nothing to do with sculpture, but I would like to end by briefly considering the epilogue to the tale. As I said at the outset, Britain became the beneficiary of a huge exodus of talent from Central Europe in many cultural and professional fields, in the years around the 2nd World War. The sculptors who came from Vienna did not all come to escape Nazi persecution. A relatively early arrival was Willi Soukop, who accepted an invitation to Dartington Hall in 1934. Siegfried Charoux, who had been very active in left wing politics in Vienna, left in 1935 after the Dollfuss putsch. Arthur Fleischmann, probably sensing the direction of events, accompanied the Viennese ice-hockey team to S.Africa as their official doctor in 1937. From there he went to Bali and to Australia, before arriving in England in 1949. Georg Ehrlich also left in 1937, coming directly to Britain. Along with contemporaries from other parts of Europe, Peter Peri from Budapest, Franta Belsky and Karel Vogel from Czechoslovakia, they made a major impact on the British scene, less with cutting edge modernism than with their cultured figure styles, incorporating varying degrees of stylisation and expressive distortion. Having said this, their individual contributions are extraordinarily varied. Perhaps the largest gesture was Charoux' colossal group The Islanders, which was one of the most conspicuous features of the Festival of Britain. This, Margaret Garlake has argued, is indistinguishable from totalitarian sculpture, only the circumstances of the commission revealing that it is about something else entirely. It seems to me that this impression results only from its size. The homespun family group is much too soft in its contours to be mistaken for a Nazi or Stalinist work. At the opposite extreme are the introverted and frail creations of Georg Ehrlich, whose style was taken to epitomise wartime suffering, whilst it was in fact shaped much earlier under the influence of Viennese expressionism. These things Arthur Fleischmann reserved for his religious works. His more public statements are more ebullient, less inclined to dwell on the past. His collaboration on housing projects in the Vienna of the 1930s found little echo in his post-War work. Unlike Siegfried Charoux and Willi Soukop, he did no work for new housing estates in England. The interludes of Bali and Australia had intervened, bringing a positive note. The perspex figure of Lot's Wife, which Fleischmann showed at the 1957 Holland Park exhibition maybe says something about the paralysing effects of looking back. At the same time, The Miranda which he had earlier sculpted for the Festival of Britain of 1951, shows a quite commendable indifference to British cultural values and bardolatry, by not representing the Miranda of The Tempest, but a fantasy figure from a now almost forgotten film, starring Britain's chief screen idol, Glynnis Johns.

This little diversion has in itself nothing to do with sculpture, but I would like to end by briefly considering the epilogue to the tale. As I said at the outset, Britain became the beneficiary of a huge exodus of talent from Central Europe in many cultural and professional fields, in the years around the 2nd World War. The sculptors who came from Vienna did not all come to escape Nazi persecution. A relatively early arrival was Willi Soukop, who accepted an invitation to Dartington Hall in 1934. Siegfried Charoux, who had been very active in left wing politics in Vienna, left in 1935 after the Dollfuss putsch. Arthur Fleischmann, probably sensing the direction of events, accompanied the Viennese ice-hockey team to S.Africa as their official doctor in 1937. From there he went to Bali and to Australia, before arriving in England in 1949. Georg Ehrlich also left in 1937, coming directly to Britain. Along with contemporaries from other parts of Europe, Peter Peri from Budapest, Franta Belsky and Karel Vogel from Czechoslovakia, they made a major impact on the British scene, less with cutting edge modernism than with their cultured figure styles, incorporating varying degrees of stylisation and expressive distortion. Having said this, their individual contributions are extraordinarily varied. Perhaps the largest gesture was Charoux' colossal group The Islanders, which was one of the most conspicuous features of the Festival of Britain. This, Margaret Garlake has argued, is indistinguishable from totalitarian sculpture, only the circumstances of the commission revealing that it is about something else entirely. It seems to me that this impression results only from its size. The homespun family group is much too soft in its contours to be mistaken for a Nazi or Stalinist work. At the opposite extreme are the introverted and frail creations of Georg Ehrlich, whose style was taken to epitomise wartime suffering, whilst it was in fact shaped much earlier under the influence of Viennese expressionism. These things Arthur Fleischmann reserved for his religious works. His more public statements are more ebullient, less inclined to dwell on the past. His collaboration on housing projects in the Vienna of the 1930s found little echo in his post-War work. Unlike Siegfried Charoux and Willi Soukop, he did no work for new housing estates in England. The interludes of Bali and Australia had intervened, bringing a positive note. The perspex figure of Lot's Wife, which Fleischmann showed at the 1957 Holland Park exhibition maybe says something about the paralysing effects of looking back. At the same time, The Miranda which he had earlier sculpted for the Festival of Britain of 1951, shows a quite commendable indifference to British cultural values and bardolatry, by not representing the Miranda of The Tempest, but a fantasy figure from a now almost forgotten film, starring Britain's chief screen idol, Glynnis Johns.

|

|

|

Photo Credits

|

|

Conway Library of the Courtauld Institute of Art

|

1-4, 7, 9-15, 20-22

|

|

T. Benton

|

5, 6, 8

|

|

Images from the A. Fleischmann Archive

|

16-19, 23-25

|

|

|

Until the Viennese experiment, which I have to insist was something of a first, the aesthetic element in public housing projects was limited to purely architectural invention. It is generally recognised that the breakthrough into a more comely style of public housing was achieved by the LCC, in its slum clearance projects of the 1890s. The first of these was the Boundary Street Estate, which replaced a particularly frightening and squalid area called the Old Nichol in the western part of Bethnal Green, not far from Shoreditch. On the LCC estates, the oppressive effect of the necessarily very tall blocks was offset by the variety of brick patterns, decorative ironwork, and the charm of some of the entrance porches. These estates are sculpture free. A closer approach to the Viennese example was the provision of art in privately financed garden cities. At Port Sunlight, the Lever family made over its art collection for enjoyment by the community, which consisted of operatives in the Sunlight Soap factory. The collection was housed in a rather grand building on the central avenue of this garden city. It contains quite a lot of sculpture. A monument to First Lord Leverhulme was placed outside the gallery much later, but after World War 1, Port Sunlight got a very large War Memorial, which celebrates family values and the cohesion of the community in the hour of peril. Another turn of the century Garden City, Whiteley Village in Surrey has at its centre, in the style of old almshouses an allegorical memorial commemorating the founder. This memorial was the work of George Frampton, the sculptor whose studio Arthur Fleischmann occupied from 1958 to 1990.

Until the Viennese experiment, which I have to insist was something of a first, the aesthetic element in public housing projects was limited to purely architectural invention. It is generally recognised that the breakthrough into a more comely style of public housing was achieved by the LCC, in its slum clearance projects of the 1890s. The first of these was the Boundary Street Estate, which replaced a particularly frightening and squalid area called the Old Nichol in the western part of Bethnal Green, not far from Shoreditch. On the LCC estates, the oppressive effect of the necessarily very tall blocks was offset by the variety of brick patterns, decorative ironwork, and the charm of some of the entrance porches. These estates are sculpture free. A closer approach to the Viennese example was the provision of art in privately financed garden cities. At Port Sunlight, the Lever family made over its art collection for enjoyment by the community, which consisted of operatives in the Sunlight Soap factory. The collection was housed in a rather grand building on the central avenue of this garden city. It contains quite a lot of sculpture. A monument to First Lord Leverhulme was placed outside the gallery much later, but after World War 1, Port Sunlight got a very large War Memorial, which celebrates family values and the cohesion of the community in the hour of peril. Another turn of the century Garden City, Whiteley Village in Surrey has at its centre, in the style of old almshouses an allegorical memorial commemorating the founder. This memorial was the work of George Frampton, the sculptor whose studio Arthur Fleischmann occupied from 1958 to 1990.

Little attention has been given to the interwar experiments with community sculpture. One of the reasons for this is that, after the 2nd World War the main architectural histories excluded the Viennese housing projects from the record. Their monumentalism and failure to exploit modern methods of mass-production consigned them to an artistic limbo. The main advances in the period were seen as having taken place in Berlin, Stuttgart and North West Holland. Under the influence of Bauhaus teaching and De Stijl theory, the German and Dutch estates were characterised by clean-lined functional minimalism. Not only were they devoid of any architectural ornament, but the neighbourhoods were mainly free of sculpture. Amsterdam was the only exception acknowledged in these histories. There, an expressionist brick idiom, originated in the immediate post-War years by the group called Wendingen, continued unabated. This brick architecture was accompanied on major public and commercial building by idiosyncratic, and often bizarre, sculptural features. However, these did not reach the very large housing estates built in the Amsterdam suburbs in this period.

Little attention has been given to the interwar experiments with community sculpture. One of the reasons for this is that, after the 2nd World War the main architectural histories excluded the Viennese housing projects from the record. Their monumentalism and failure to exploit modern methods of mass-production consigned them to an artistic limbo. The main advances in the period were seen as having taken place in Berlin, Stuttgart and North West Holland. Under the influence of Bauhaus teaching and De Stijl theory, the German and Dutch estates were characterised by clean-lined functional minimalism. Not only were they devoid of any architectural ornament, but the neighbourhoods were mainly free of sculpture. Amsterdam was the only exception acknowledged in these histories. There, an expressionist brick idiom, originated in the immediate post-War years by the group called Wendingen, continued unabated. This brick architecture was accompanied on major public and commercial building by idiosyncratic, and often bizarre, sculptural features. However, these did not reach the very large housing estates built in the Amsterdam suburbs in this period.

Another series of photographs in the Fleischmann archive are identified in handwritten descriptions on their backs, as representing a Gemeinde Wien bathing establishment, and the name of an architect is given, unfortunately illegibly. The relief panel provided by Arthur Fleischmann is clearly in high toned, coloured terracotta, and represents two naked children, one holding a kite, and the other the ball of kite string. It was one of the chief claims to success of the socialist regime, that it had procured the opportunity for health-giving exercise to a population, which had been suffering all the ill effects of malnutrition and overcrowding during and after the First World War. Bathing and paddling pools were a major feature of this therapeutic programme. The third piece is especially interesting, since it is symbolic of the home-building activities themselves. It is in the form of a triptych, with in one side panel an architect, in the other a bricklayer, and in the centre a monumental group of a mother and two children. The relief is illustrated in Forum, an art periodical of the time. The magazine states that the work symbolizes the genesis of the house, that it was for one of the Wiener Arbeiterhäuser, and goes on to praise Fleischmann's work for the originality of the thought behind it and the clarity of the composition. An article on Fleischmann's work in a later number of Forum, which appeared after the downfall of the socialist local government in Vienna, refers back to the work which Fleischmann had done for the Viennese workers' dwellings. The article mentions the progress which Fleischmann's work had made from the rather cool anatomical accuracy of his earliest pieces, which reflected his training in medicine, towards a greater stylisation. It also pointed out that the architectural sculpture episode had given him the chance to investigate the peculiar qualities of materials, in this case, one imagines, the effect and durability of different sorts of architectural ceramic. The Genesis of the House triptych as we can call it, certainly reflects the tendency to stylisation, with the hieratic gestures of the architect and builder, and the almost geometrical arrangement of the limbs of the central family group.

Another series of photographs in the Fleischmann archive are identified in handwritten descriptions on their backs, as representing a Gemeinde Wien bathing establishment, and the name of an architect is given, unfortunately illegibly. The relief panel provided by Arthur Fleischmann is clearly in high toned, coloured terracotta, and represents two naked children, one holding a kite, and the other the ball of kite string. It was one of the chief claims to success of the socialist regime, that it had procured the opportunity for health-giving exercise to a population, which had been suffering all the ill effects of malnutrition and overcrowding during and after the First World War. Bathing and paddling pools were a major feature of this therapeutic programme. The third piece is especially interesting, since it is symbolic of the home-building activities themselves. It is in the form of a triptych, with in one side panel an architect, in the other a bricklayer, and in the centre a monumental group of a mother and two children. The relief is illustrated in Forum, an art periodical of the time. The magazine states that the work symbolizes the genesis of the house, that it was for one of the Wiener Arbeiterhäuser, and goes on to praise Fleischmann's work for the originality of the thought behind it and the clarity of the composition. An article on Fleischmann's work in a later number of Forum, which appeared after the downfall of the socialist local government in Vienna, refers back to the work which Fleischmann had done for the Viennese workers' dwellings. The article mentions the progress which Fleischmann's work had made from the rather cool anatomical accuracy of his earliest pieces, which reflected his training in medicine, towards a greater stylisation. It also pointed out that the architectural sculpture episode had given him the chance to investigate the peculiar qualities of materials, in this case, one imagines, the effect and durability of different sorts of architectural ceramic. The Genesis of the House triptych as we can call it, certainly reflects the tendency to stylisation, with the hieratic gestures of the architect and builder, and the almost geometrical arrangement of the limbs of the central family group.

The society's largest development within the Somers Town area was the Sidney Street Estate, which Hamilton explained was based on the Viennese model, and on recollections of English collegiate buildings and almshouses. In some of the earlier buildings of the society, rather minimal sculpted features had been included; some della Robbia plaques, and a figure of the Virgin on a conspicuous corner of one of the first blocks. The figure of the Virgin was sculpted, we are told, by "the mother of the architect". In drawing up the designs for the Sidney Street estate, Hamilton included a number of features in coloured ceramic modelled by the already well-established sculptor, Gilbert Bayes, and made by the Doulton company. At Sidney Street these consisted of lunettes over the first floor windows, with roundels illustrating Hans Andersen's fairy stories, and washing post finials, many of them based on nursery rhymes. There was also a statue of St. Anthony and his donkey for the St. Anthony block and a relief of the Four Seasons around the clock on the central courtyard. Hamilton hoped that sponsors would come forward for other features, such as an ornamental fountain. To this end the Treasurer of the society set up a fund called "Gardens, Sculpture and Gates", in the hope that these things could be "provided more nobly than the society is able to do from its own resources". This initiative is now recognised to have been a first in Britain, and it must be the model for the policy adopted in the post-War period for LCC estates and New Towns. Although Vienna is much talked about in the society newsletter, it is not mentioned specifically in relation to the sculpture issue, but I do feel that it must have played a part in inspiring this new development. Fairy stories and nursery rhymes were often illustrated in the painted decoration of Vienna's municipal blocks. My view is further supported by the fact that courses in painting, introduced for the benefit of the children on the Somers-Town estate in the early thirties, and intended to develop their powers of creative self-expression, followed principles advocated by a Professor Cizek of Vienna.

The society's largest development within the Somers Town area was the Sidney Street Estate, which Hamilton explained was based on the Viennese model, and on recollections of English collegiate buildings and almshouses. In some of the earlier buildings of the society, rather minimal sculpted features had been included; some della Robbia plaques, and a figure of the Virgin on a conspicuous corner of one of the first blocks. The figure of the Virgin was sculpted, we are told, by "the mother of the architect". In drawing up the designs for the Sidney Street estate, Hamilton included a number of features in coloured ceramic modelled by the already well-established sculptor, Gilbert Bayes, and made by the Doulton company. At Sidney Street these consisted of lunettes over the first floor windows, with roundels illustrating Hans Andersen's fairy stories, and washing post finials, many of them based on nursery rhymes. There was also a statue of St. Anthony and his donkey for the St. Anthony block and a relief of the Four Seasons around the clock on the central courtyard. Hamilton hoped that sponsors would come forward for other features, such as an ornamental fountain. To this end the Treasurer of the society set up a fund called "Gardens, Sculpture and Gates", in the hope that these things could be "provided more nobly than the society is able to do from its own resources". This initiative is now recognised to have been a first in Britain, and it must be the model for the policy adopted in the post-War period for LCC estates and New Towns. Although Vienna is much talked about in the society newsletter, it is not mentioned specifically in relation to the sculpture issue, but I do feel that it must have played a part in inspiring this new development. Fairy stories and nursery rhymes were often illustrated in the painted decoration of Vienna's municipal blocks. My view is further supported by the fact that courses in painting, introduced for the benefit of the children on the Somers-Town estate in the early thirties, and intended to develop their powers of creative self-expression, followed principles advocated by a Professor Cizek of Vienna.

This little diversion has in itself nothing to do with sculpture, but I would like to end by briefly considering the epilogue to the tale. As I said at the outset, Britain became the beneficiary of a huge exodus of talent from Central Europe in many cultural and professional fields, in the years around the 2nd World War. The sculptors who came from Vienna did not all come to escape Nazi persecution. A relatively early arrival was Willi Soukop, who accepted an invitation to Dartington Hall in 1934. Siegfried Charoux, who had been very active in left wing politics in Vienna, left in 1935 after the Dollfuss putsch. Arthur Fleischmann, probably sensing the direction of events, accompanied the Viennese ice-hockey team to S.Africa as their official doctor in 1937. From there he went to Bali and to Australia, before arriving in England in 1949. Georg Ehrlich also left in 1937, coming directly to Britain. Along with contemporaries from other parts of Europe, Peter Peri from Budapest, Franta Belsky and Karel Vogel from Czechoslovakia, they made a major impact on the British scene, less with cutting edge modernism than with their cultured figure styles, incorporating varying degrees of stylisation and expressive distortion. Having said this, their individual contributions are extraordinarily varied. Perhaps the largest gesture was Charoux' colossal group The Islanders, which was one of the most conspicuous features of the Festival of Britain. This, Margaret Garlake has argued, is indistinguishable from totalitarian sculpture, only the circumstances of the commission revealing that it is about something else entirely. It seems to me that this impression results only from its size. The homespun family group is much too soft in its contours to be mistaken for a Nazi or Stalinist work. At the opposite extreme are the introverted and frail creations of Georg Ehrlich, whose style was taken to epitomise wartime suffering, whilst it was in fact shaped much earlier under the influence of Viennese expressionism. These things Arthur Fleischmann reserved for his religious works. His more public statements are more ebullient, less inclined to dwell on the past. His collaboration on housing projects in the Vienna of the 1930s found little echo in his post-War work. Unlike Siegfried Charoux and Willi Soukop, he did no work for new housing estates in England. The interludes of Bali and Australia had intervened, bringing a positive note. The perspex figure of Lot's Wife, which Fleischmann showed at the 1957 Holland Park exhibition maybe says something about the paralysing effects of looking back. At the same time, The Miranda which he had earlier sculpted for the Festival of Britain of 1951, shows a quite commendable indifference to British cultural values and bardolatry, by not representing the Miranda of The Tempest, but a fantasy figure from a now almost forgotten film, starring Britain's chief screen idol, Glynnis Johns.

This little diversion has in itself nothing to do with sculpture, but I would like to end by briefly considering the epilogue to the tale. As I said at the outset, Britain became the beneficiary of a huge exodus of talent from Central Europe in many cultural and professional fields, in the years around the 2nd World War. The sculptors who came from Vienna did not all come to escape Nazi persecution. A relatively early arrival was Willi Soukop, who accepted an invitation to Dartington Hall in 1934. Siegfried Charoux, who had been very active in left wing politics in Vienna, left in 1935 after the Dollfuss putsch. Arthur Fleischmann, probably sensing the direction of events, accompanied the Viennese ice-hockey team to S.Africa as their official doctor in 1937. From there he went to Bali and to Australia, before arriving in England in 1949. Georg Ehrlich also left in 1937, coming directly to Britain. Along with contemporaries from other parts of Europe, Peter Peri from Budapest, Franta Belsky and Karel Vogel from Czechoslovakia, they made a major impact on the British scene, less with cutting edge modernism than with their cultured figure styles, incorporating varying degrees of stylisation and expressive distortion. Having said this, their individual contributions are extraordinarily varied. Perhaps the largest gesture was Charoux' colossal group The Islanders, which was one of the most conspicuous features of the Festival of Britain. This, Margaret Garlake has argued, is indistinguishable from totalitarian sculpture, only the circumstances of the commission revealing that it is about something else entirely. It seems to me that this impression results only from its size. The homespun family group is much too soft in its contours to be mistaken for a Nazi or Stalinist work. At the opposite extreme are the introverted and frail creations of Georg Ehrlich, whose style was taken to epitomise wartime suffering, whilst it was in fact shaped much earlier under the influence of Viennese expressionism. These things Arthur Fleischmann reserved for his religious works. His more public statements are more ebullient, less inclined to dwell on the past. His collaboration on housing projects in the Vienna of the 1930s found little echo in his post-War work. Unlike Siegfried Charoux and Willi Soukop, he did no work for new housing estates in England. The interludes of Bali and Australia had intervened, bringing a positive note. The perspex figure of Lot's Wife, which Fleischmann showed at the 1957 Holland Park exhibition maybe says something about the paralysing effects of looking back. At the same time, The Miranda which he had earlier sculpted for the Festival of Britain of 1951, shows a quite commendable indifference to British cultural values and bardolatry, by not representing the Miranda of The Tempest, but a fantasy figure from a now almost forgotten film, starring Britain's chief screen idol, Glynnis Johns.