|

Most of what Margaret Garlake says about her artists applies also to the other two in my selection. My main claim for mine is that it has this firm biographical basis which comes accompanied by a certain amount of amusing anecdote. I would also claim that the odysseys of my artists demonstrates rather better the effects of the social and political upheaval in Central Europe in the 1930s and 40s. At the time of their births, all three of these sculptors were subjects of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Charoux was born in 1896 in Vienna itself, son of a dressmaker of Czech origins and an Austrian army officer. He grew into a big blond man, and with the name Siegfried, but it seems he was known familiarly in the 20s and 30s as Jud Rot Katz, which has been amusingly translated by someone called Guy Slatter, as the Jewish Ginger Tom. The proposal under the Nazis to remove his statue of Lessing was made on the grounds that it was by a Jewish sculptor. Whatever, he got married in 1926 to Margarethe Treibl, from a Jewish family with whom in general he enjoyed a very warm relationship. In addition he made two statues of Lessing, so it is clear where his sympathies lay. Arthur Fleischmann was born in the same year in Bratislava, of Jewish origin, and would be defined under the terms of the Dual Empire as a Hungarian. Friedrich Herkner, somewhat younger, was a Sudeten German, born in 1902 in Brux, what is now called Most in Bohemia, close to the German border. Before attending the Vienna Academy, he studied at the State School of Ceramic and Technical Industry in nearby Teplitz Schanau, now Teplice.

|

|

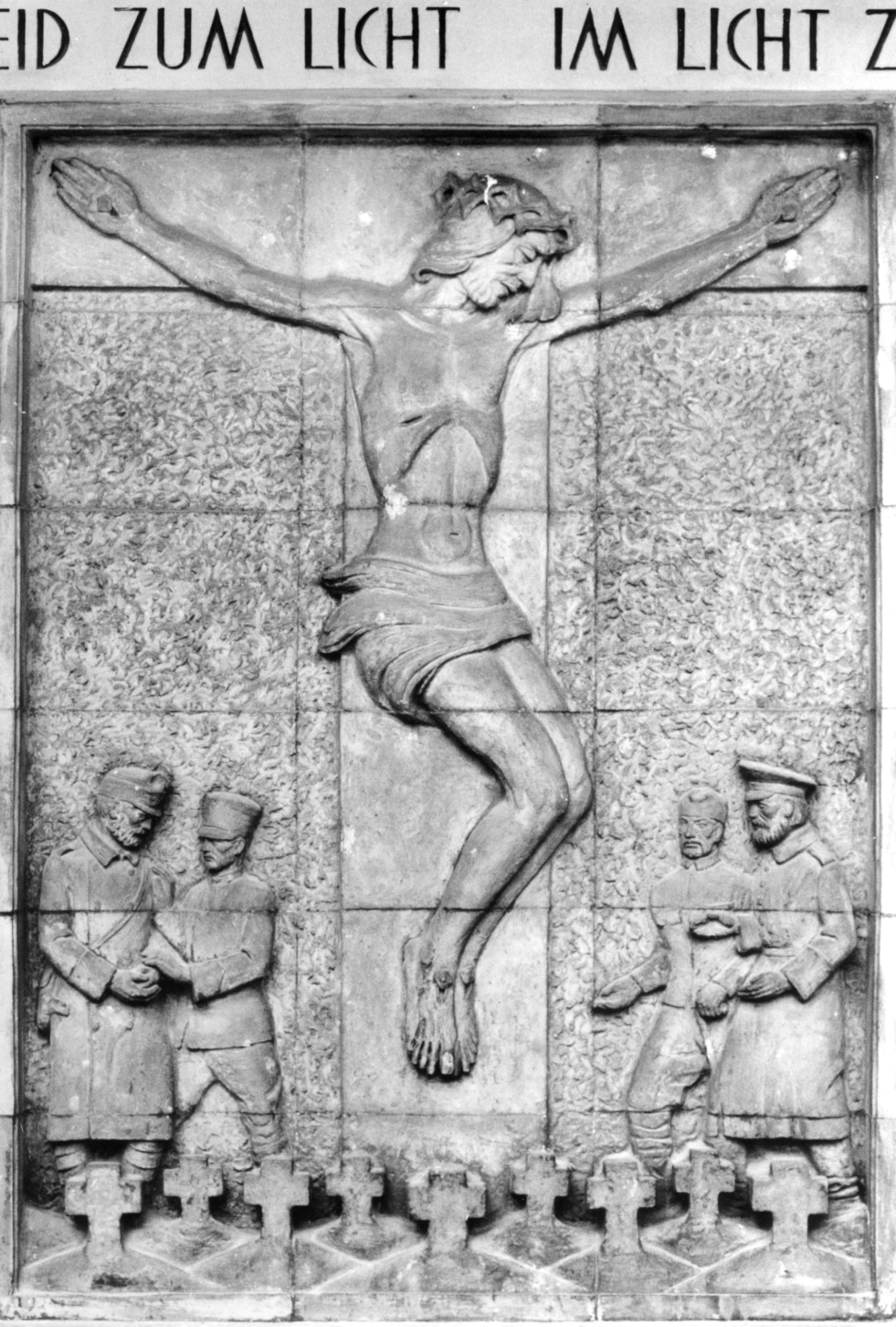

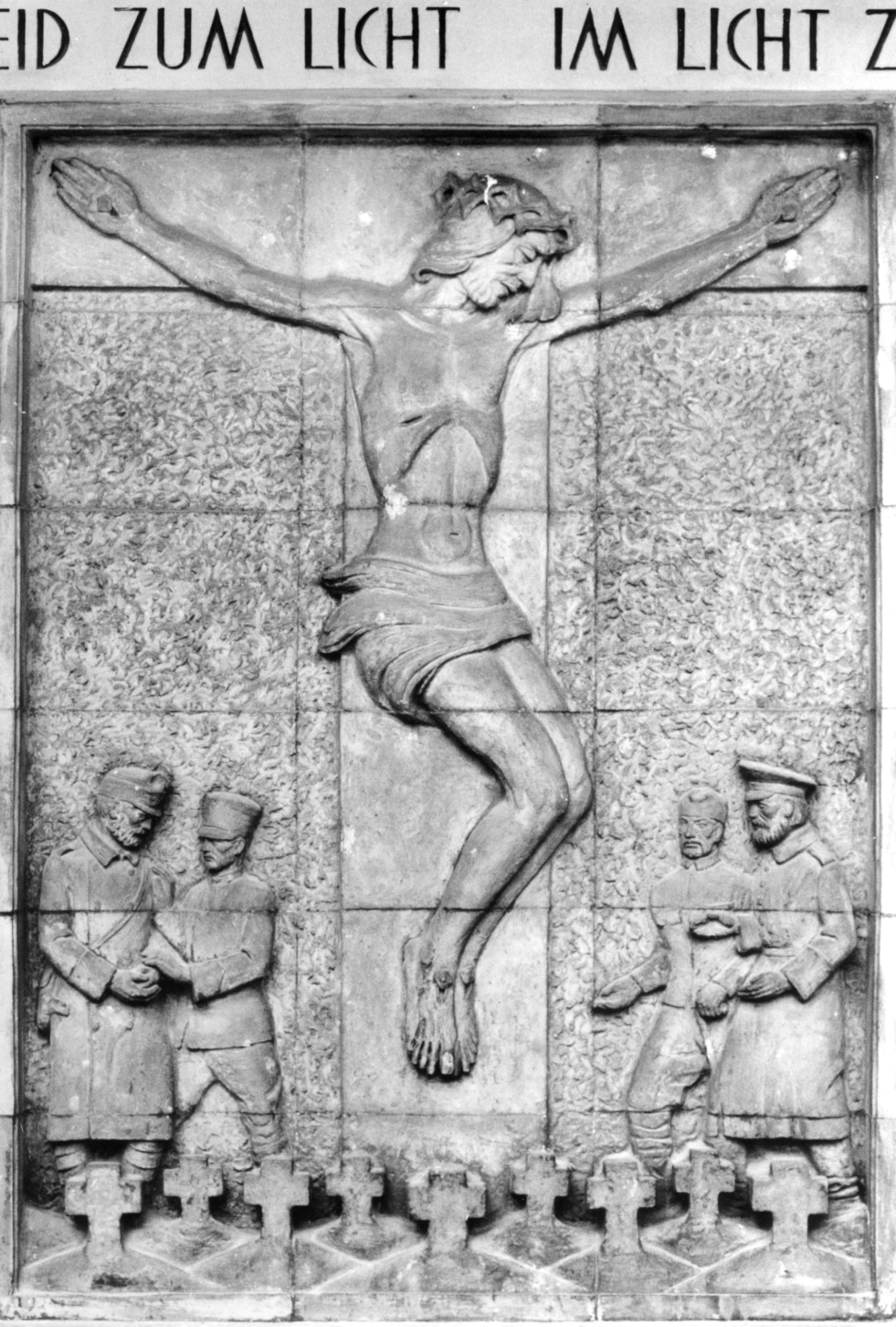

Herkner would have been too young, but both Charoux and Fleischmann served with the Austrian army in the 1914-18 war, Fleischmann as a medic with a cavalry regiment, whilst Charoux later claimed that his socialist convictions were offended by his finding himself in armed conflict with Russian peasants compelled to fight for their autocratic Tsar. Charoux was wounded and only got back the use of his right arm after an operation. Arthur Fleischmann would leave a memento to this conflict in his terracotta memorial to Austro-Hungarian prisoners who died in captivity during the war, This was erected much later, in 1933, on the Russian church in Wagramer Strasse in Vienna.

|

|

|

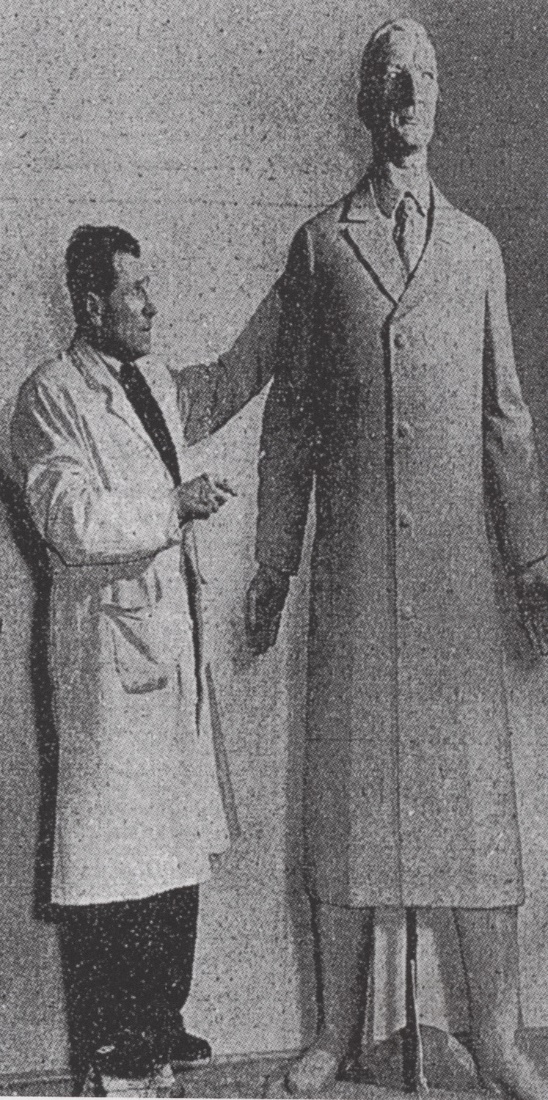

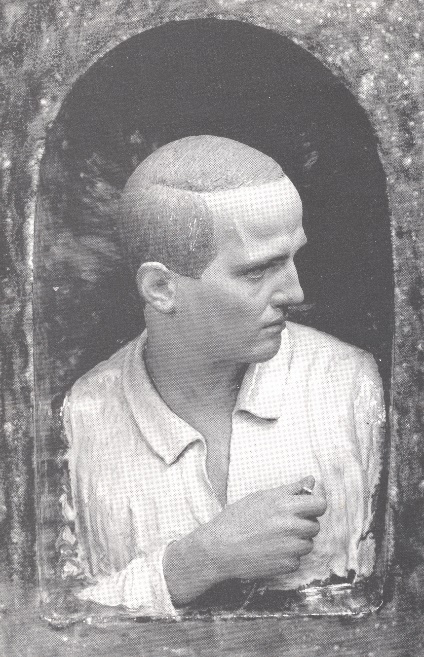

Siegfried Charoux, photograph (c1920).

|

|

|

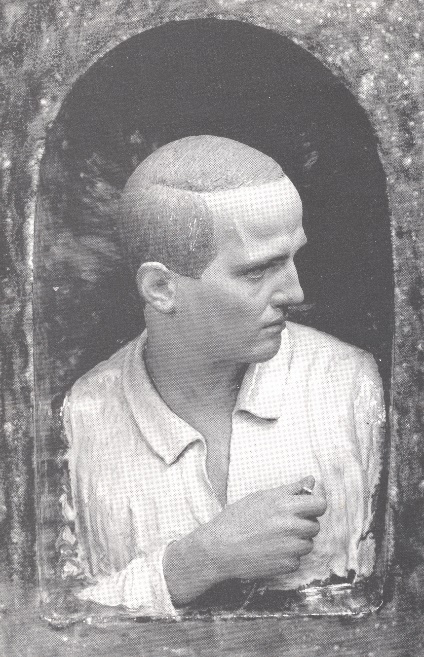

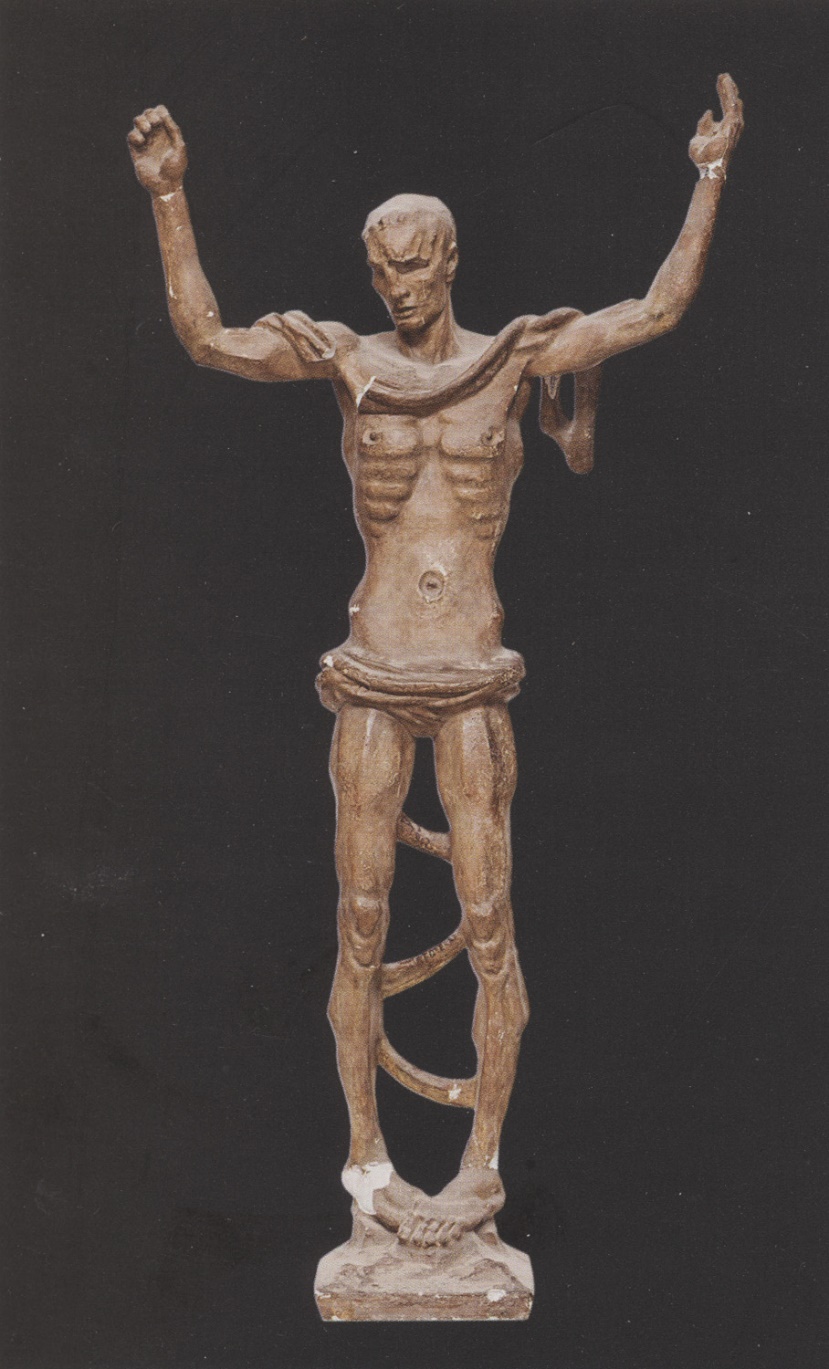

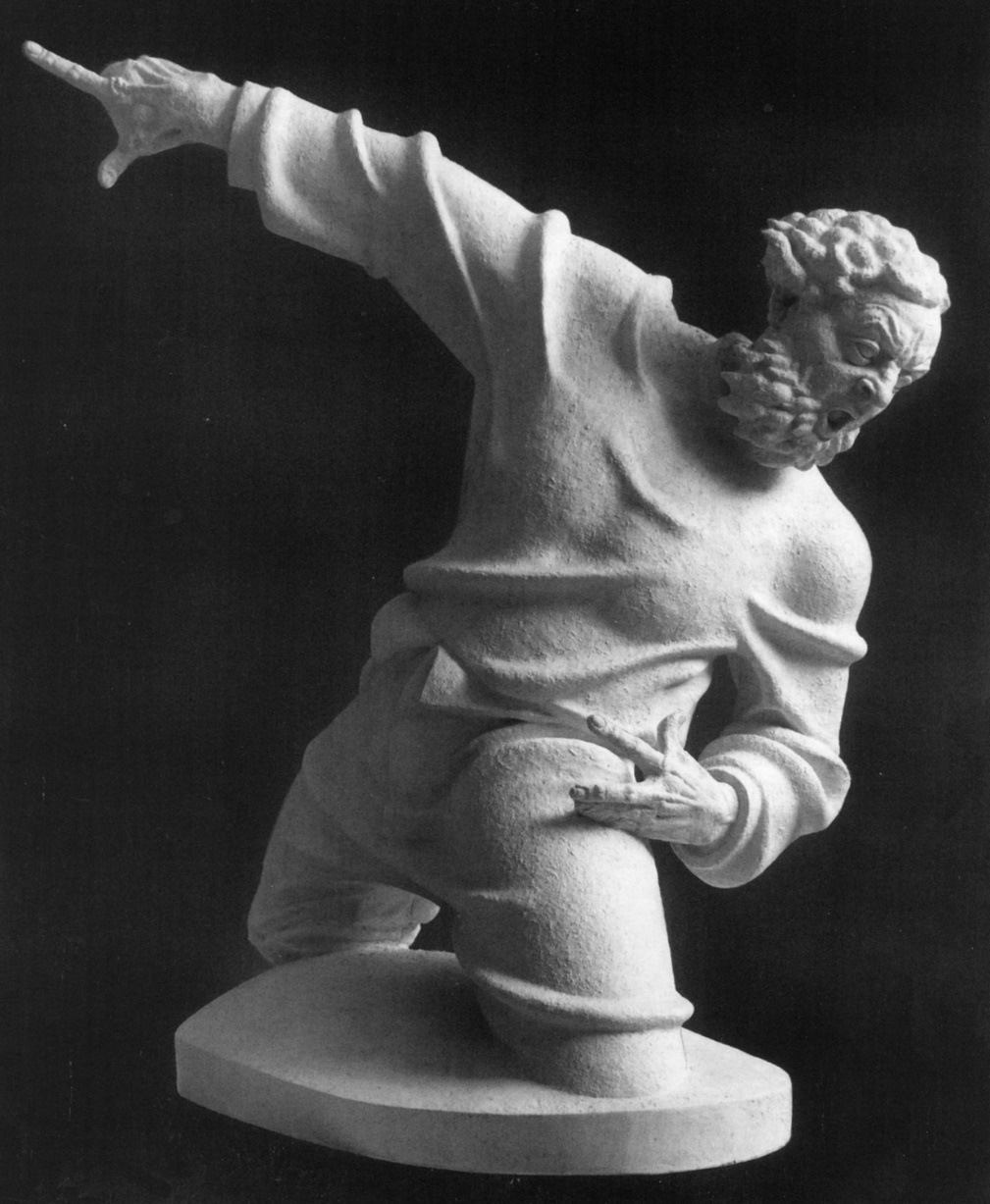

Fleischmann, Selfportrait (partially glazed terracotta), Arthur Fleischmann Museum, Bratislava.

|

|

|

Arthur Fleischmann, Memorial to Austrian soldiers who died in captivity in World War I (terracotta) 1933, Russian Church, Wagramerstrasse, Vienna.

|

|

|

Before becoming a sculptor, Arthur Fleischmann studied for a degree in medicine in Prague, a qualification which later, apparently entirely fortuitously, would take him away from a Europe threatened by Nazism. His first instruction in sculpture was also in Prague, under the Czech sculptor Jan Stursa. Charoux, on the other hand, had theatrical inclinations, wanting to be an actor, and later writing some unperformed plays. His friend David Astor tells us that during chaotic times following World War I, he crossed many frontiers of eastern Europe as a hobo, entering Russia illegally to see the revolutionary regime for himself. Judging by the flattering images he would project in the thirties of the Russian leaders, his impression was a positive one.

|

|

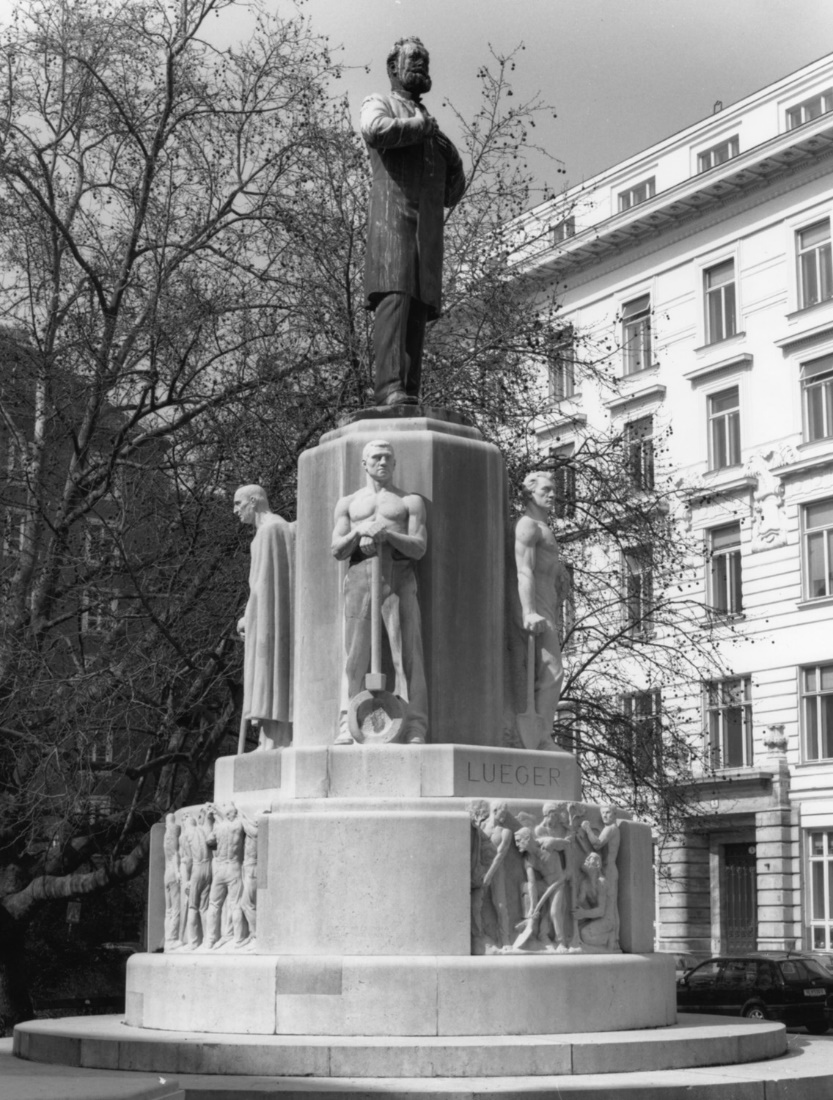

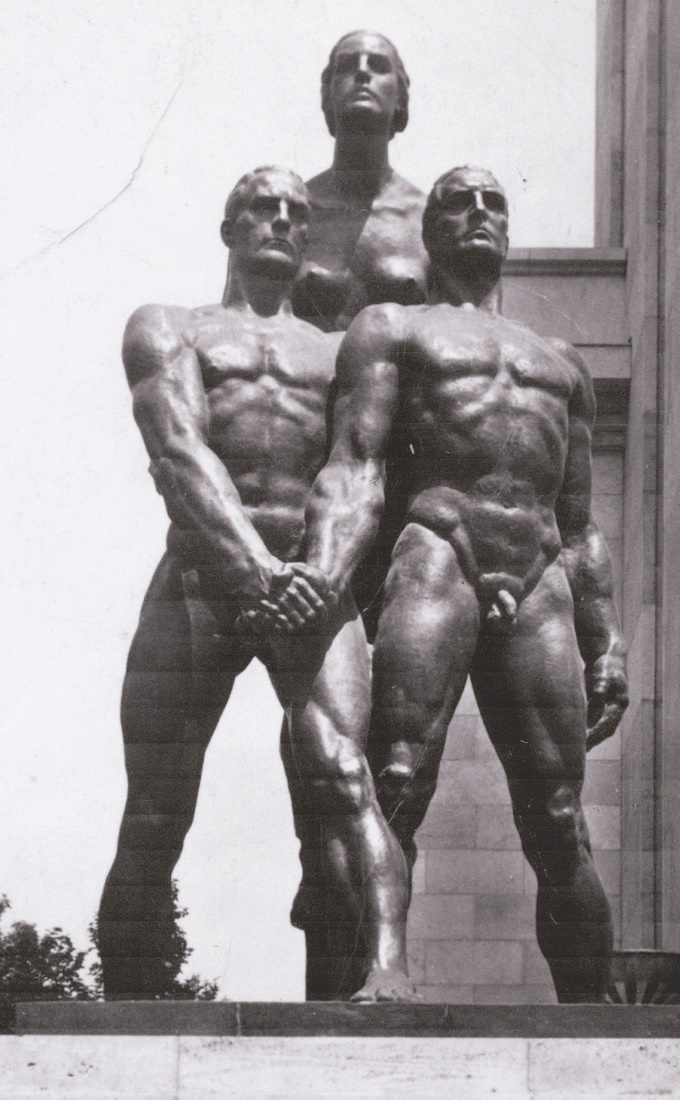

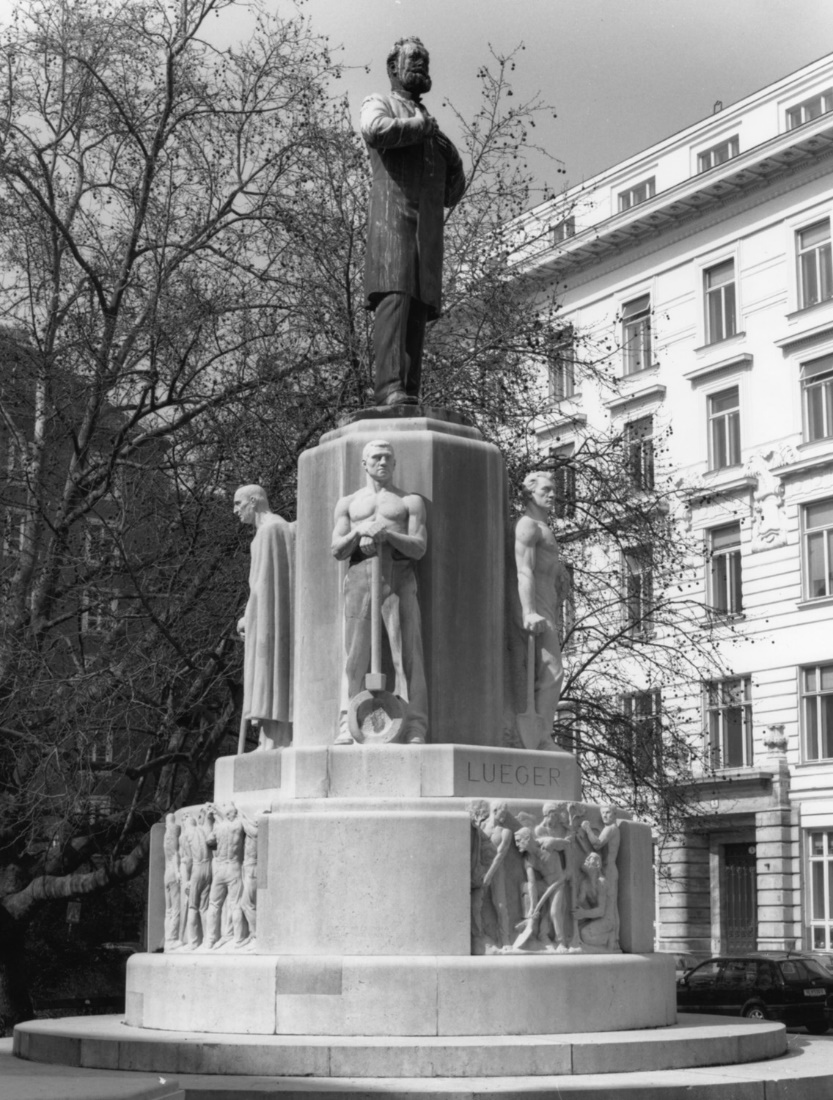

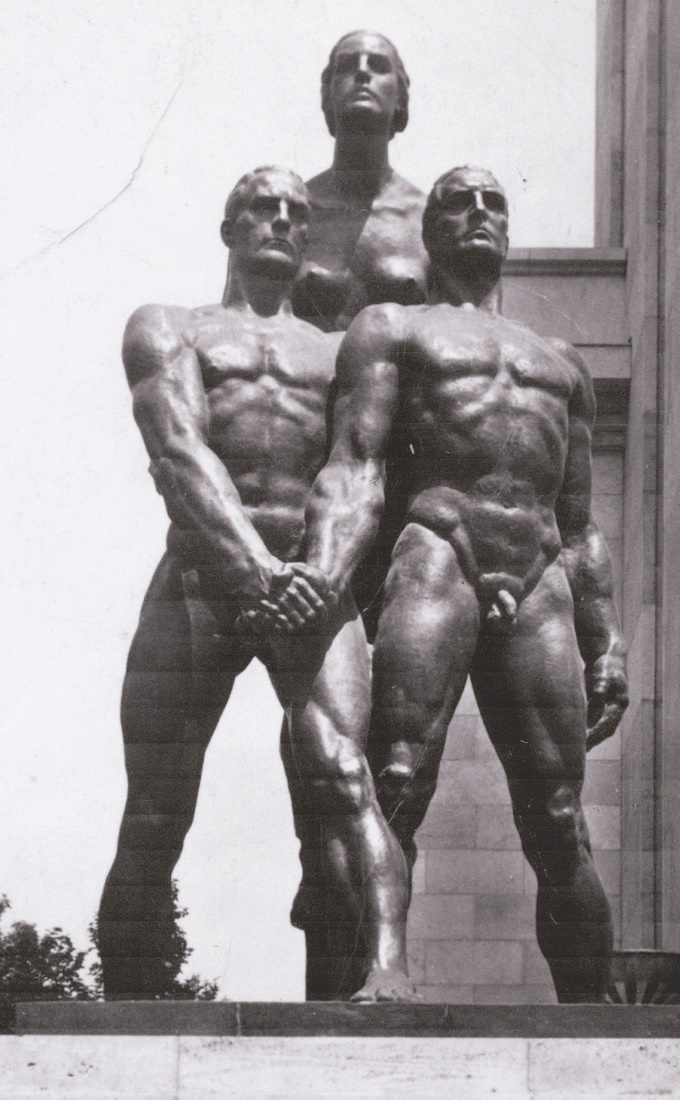

However, it was their student days in Vienna in the early 1920s which brought these three men together. They were probably all three exposed to the influence of other teachers. In the case of Charoux the names of Josef Heu, Hans Bitterlich and Anton Hanak are mentioned, and all three seem to have had contacts with the School of Applied Arts. But the head of sculpture at the Academy in these years was Josef Mullner, who had once exhibited with the Vienna Secession, but who remained wedded to a more traditional monumental style, strong, but definitely not in any sense stridently modern. Mullner most definitely did not belong to the bohemian world of Schiele and Klimt. His most visible work is the monument to the populist and ant-Semitic mayor of Vienna, Karl Lueger in the city's Luegerplatz. Adolf Hitler was an admirer of Karl Lueger, and although the Vienna Academy would famously turn Hitler down as an art student both in 1907 and 1908, the sculpture classes of Mullner had already, by the time our sculptors attended, produced a sculptor, Josef Thorak, whose muscle-bound and lugubrious heroics made him a favourite of both the Fuhrer and his architect Albert Speer.

|

|

|

Josef Mullner, Monument to Karl Lueger, 1926, Luegerplatz, Vienna.

|

|

|

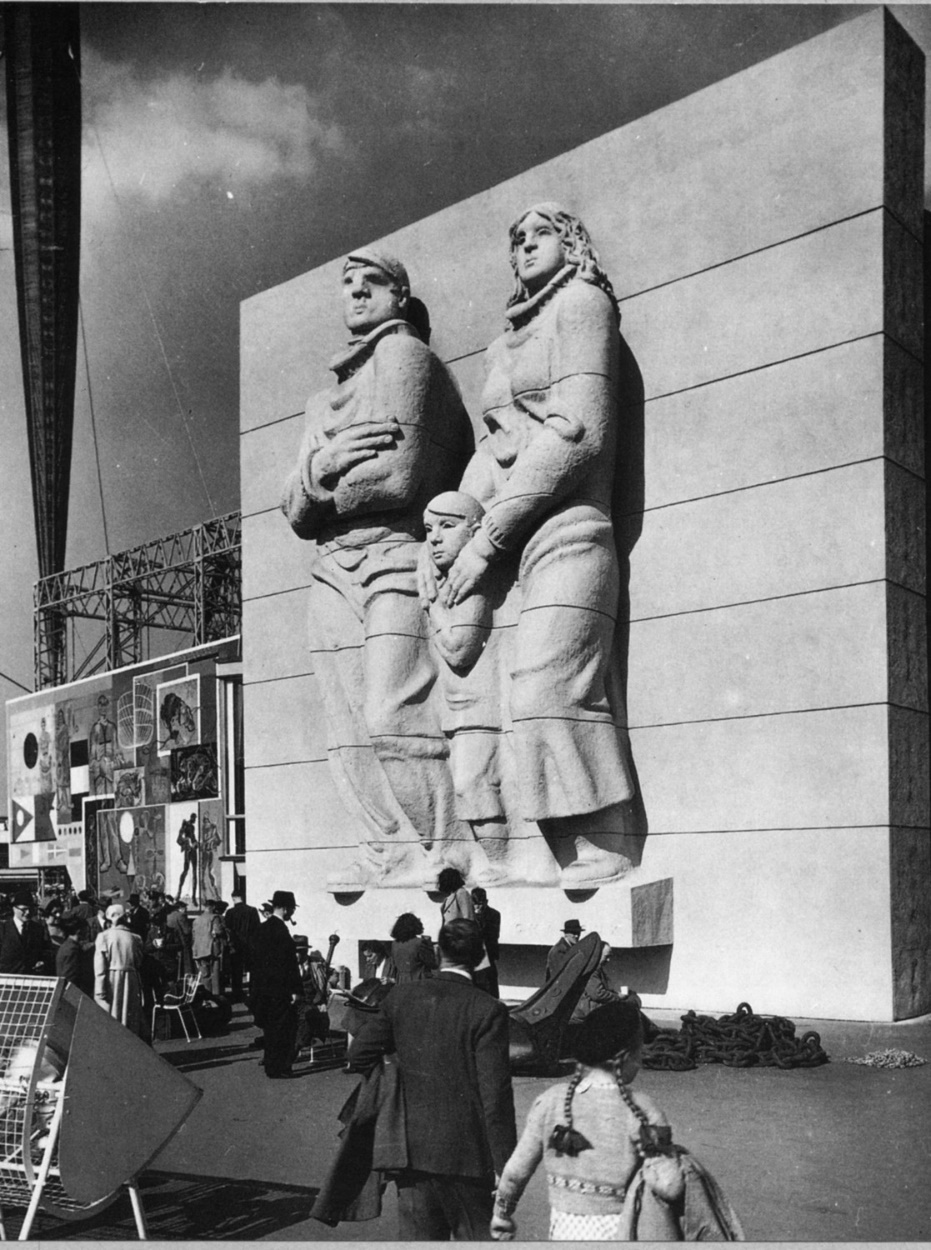

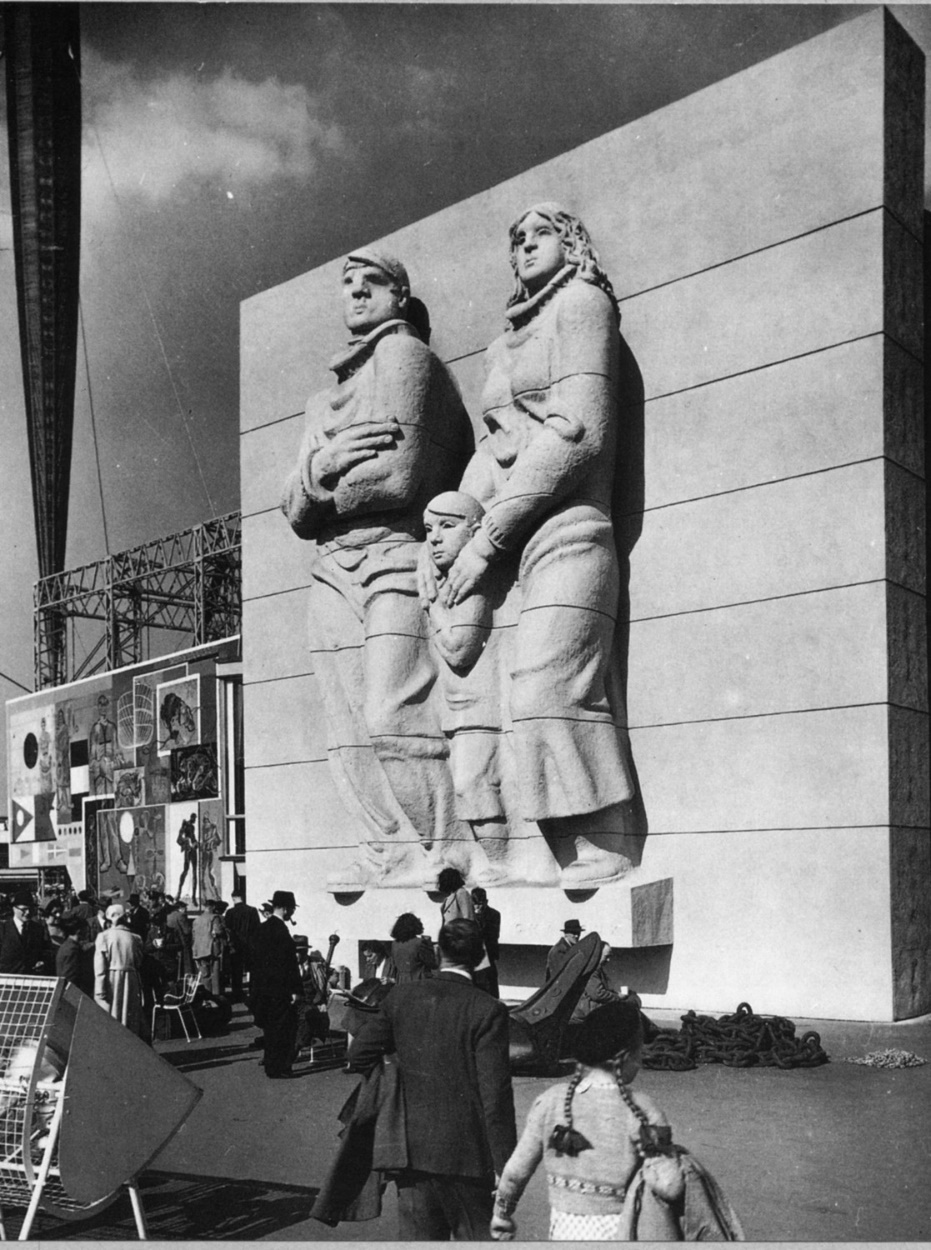

Josef Thorak, Kamaradschaft, German Pavilion, Paris World Fair, 1937.

|

|

|

Herkner, after spending some years in Vienna and winning the Academy's Rome Prize, retuned to Aussig, now called Usti nad Ladem, and set up a private art school there with courses in pottery, crafts, modelling and design. During this period he is supposed to have worked with a sculptor called Hermann Zettlitzer, another sculptor who contributed to Nazi projects.

Vienna was the main base for Charoux and Fleischmann during the 1920s and early 30s. The political background here was somewhat complicated, since Austria was, in these years, a country divided. The national government was dominated by the right wing, catholic Christian Social Party, whilst the local government of Vienna was in the hands of the left wing Social Democrats. This city was known as 'Das Rote Wien', or Red Vienna. There was certainly no ambiguity about the political affiliation of Charoux. There are good photographic records of what he achieved in these years, but at least three of his major monuments in Vienna were destroyed either by the Austrian fascist government of Engelbert Dollfuss and Kurt Schuschnig or by the Nazis after the Anschluss of 1939.

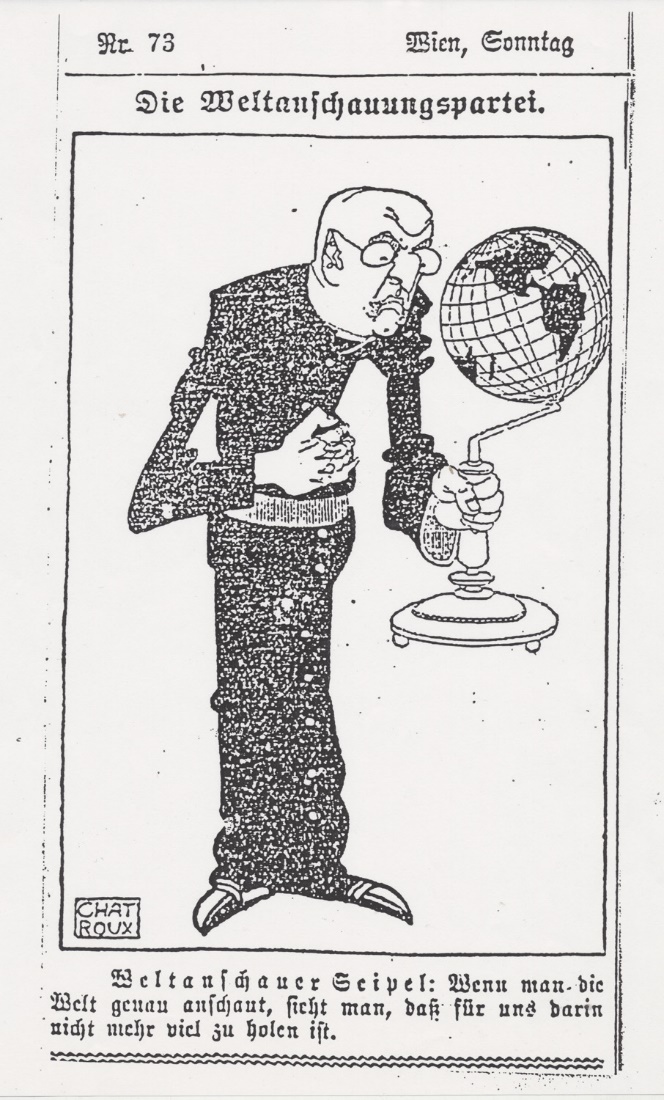

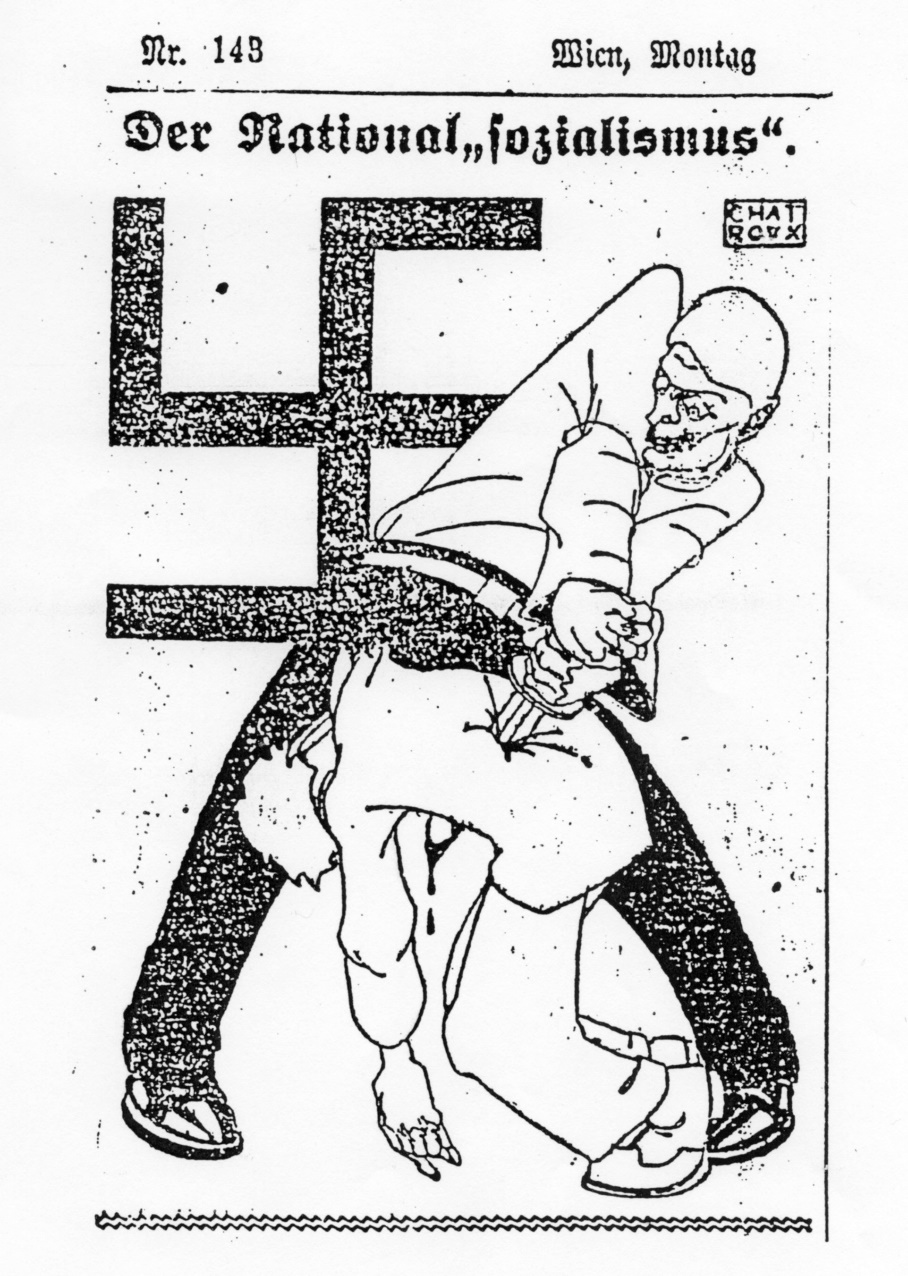

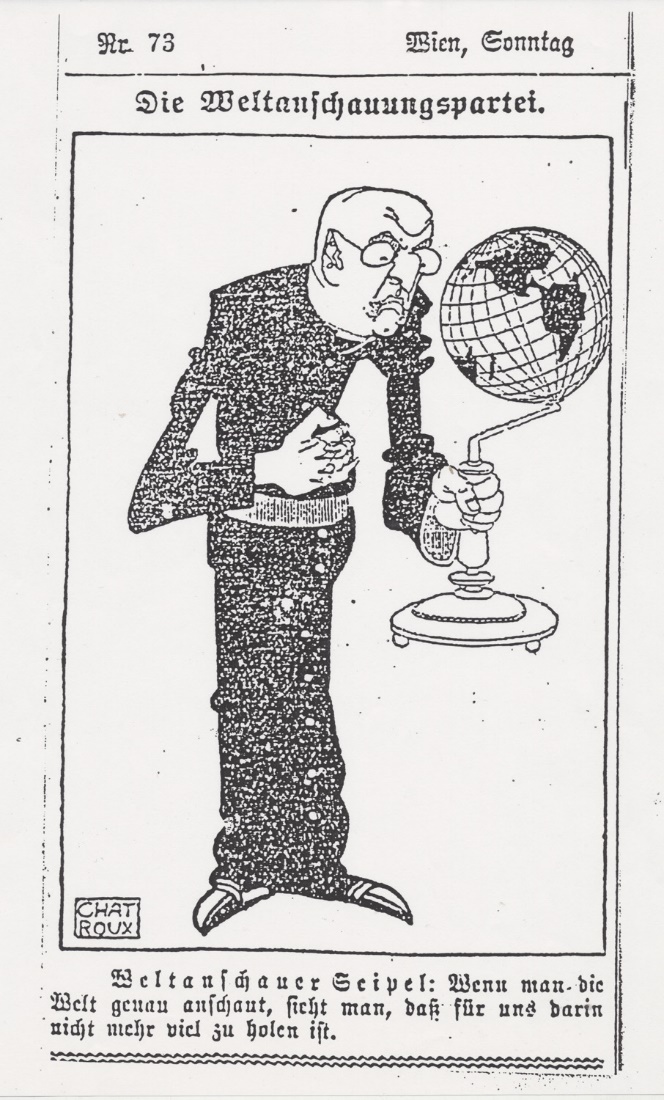

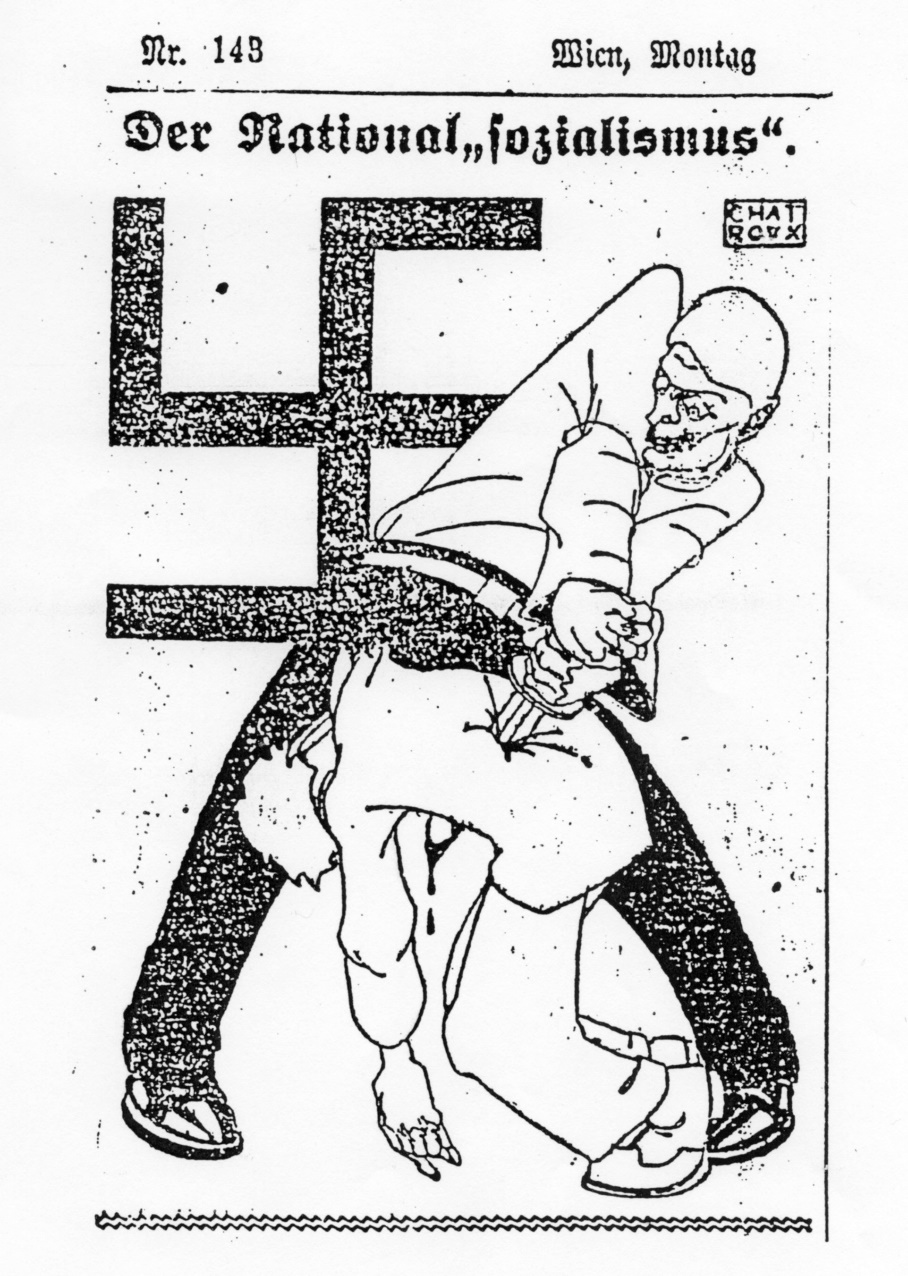

The most 'in your face' statement of these opinions are the political cartoons through which he supplemented his income in the early years. Charoux had already opted for a frenchified version of his mother's maiden name, in preference to her maiden name of Buchta, and for his caricatures he used a still further frenchified version of this, Chat Roux, or The Red Cat. A major target of these caricatures was the priest Ignaz Seipel who was, for most of the 1920s, the Christian Social Party's Chancellor in the national government, although some of the caricatures also target Germany's National Socialists, as in this example.

|

|

|

"Chat Roux" caricature from "Arbeiter Zeitung" (1925).

|

|

|

"Chat Roux" caricature from "Arbeiter Zeitung", 1926.

|

|

|

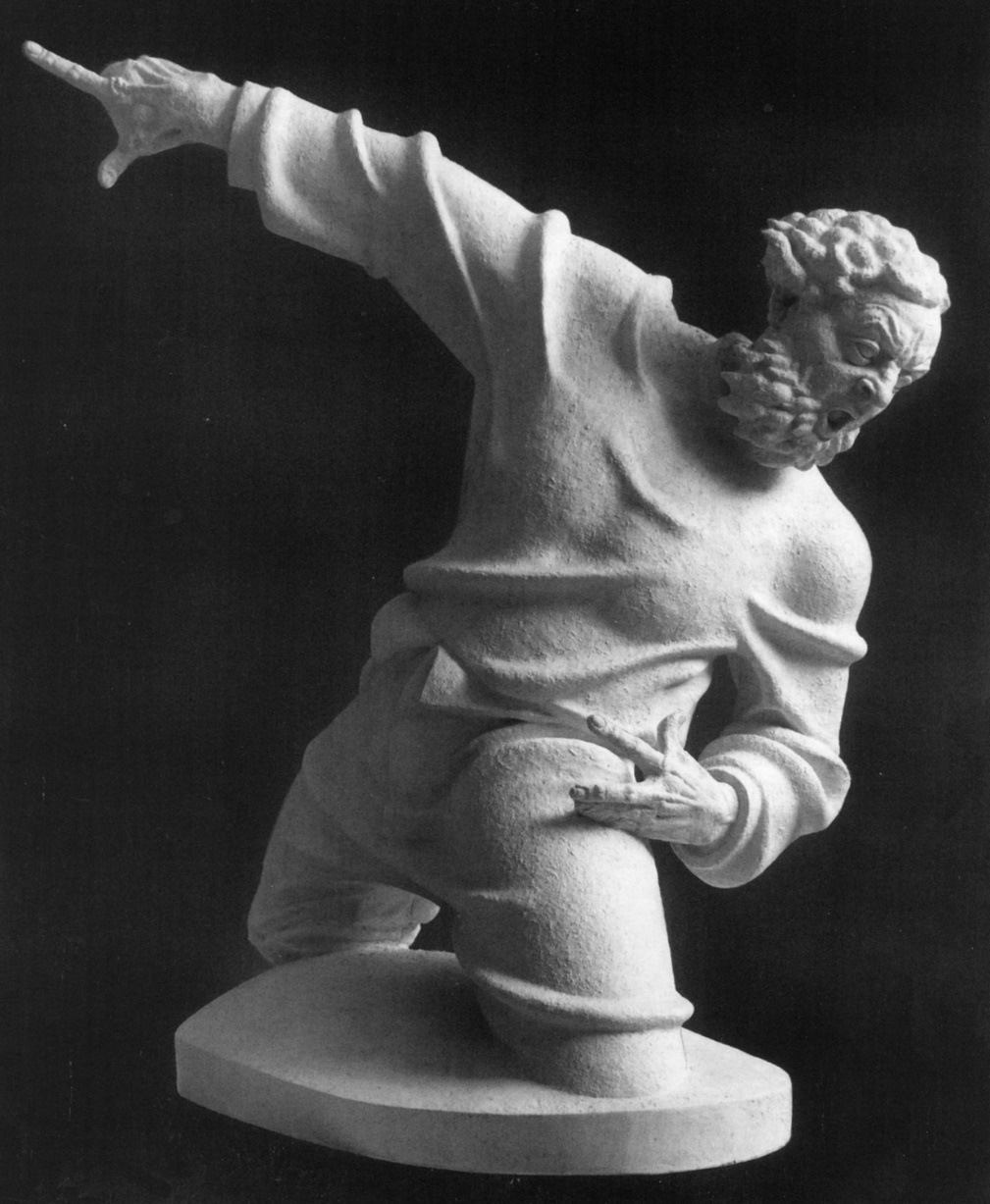

As a commemoration of the martyr of the 1848 revolution, Robert Blum, Charoux turns his subject into a sort of Energumen, almost kick-boxing his way into historical memory. A quieter commemoration, that of the playwright and philosopher Gotthold Ephram Lessing, is perhaps a more significant marker in Charoux's career. There seems to have been a long meditated project to raise a statue of Lessing in Vienna. Lessing was born and lived in Saxony. He was not a Viennese local hero, though he had visited and his works had been performed there. Since the time of its inception, this monument must have been seen as a challenge to racist, ethnocentric ideologies. Lessing was an apostle of interracial tolerance and of the relativism of ethical systems. This was all summed up in the parable of the rings in his play Nathan the Wise, a play which had been banned by the censor when it was first written towards the end of the eighteenth century, and banned once again by the Nazis. It had a Jewish hero, the Nathan of the title, though its author was the enlightened son of a Lutheran pastor.

|

|

|

Siegfried Charoux, Plaster model for statue of Robert Blum.

|

|

|

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, 1935, Judenplatz Vienna (destroyed).

|

|

|

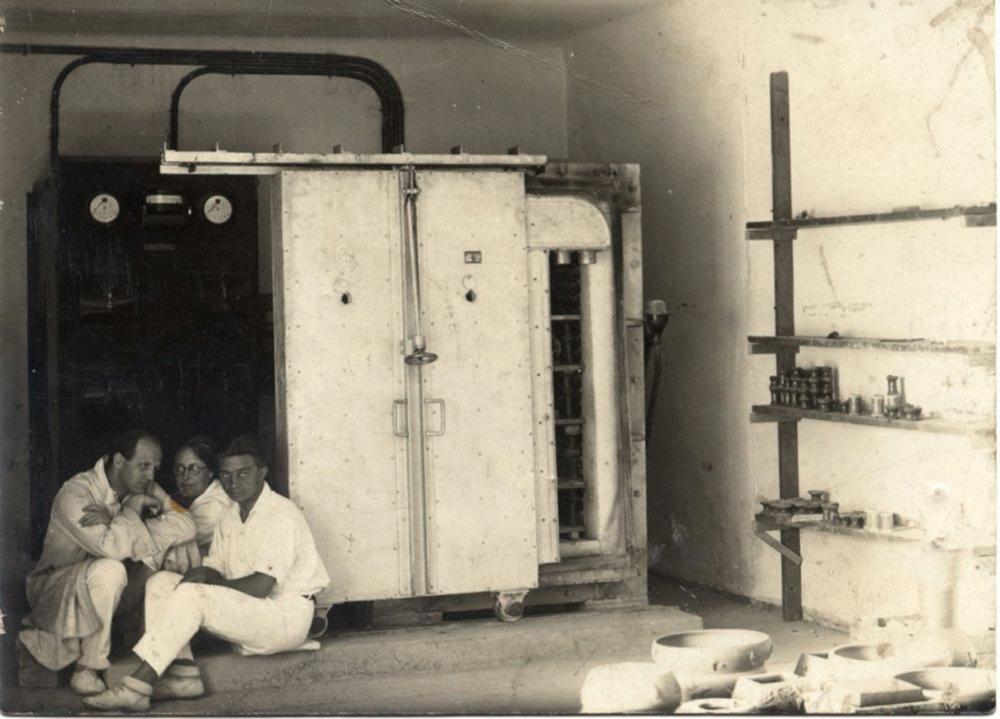

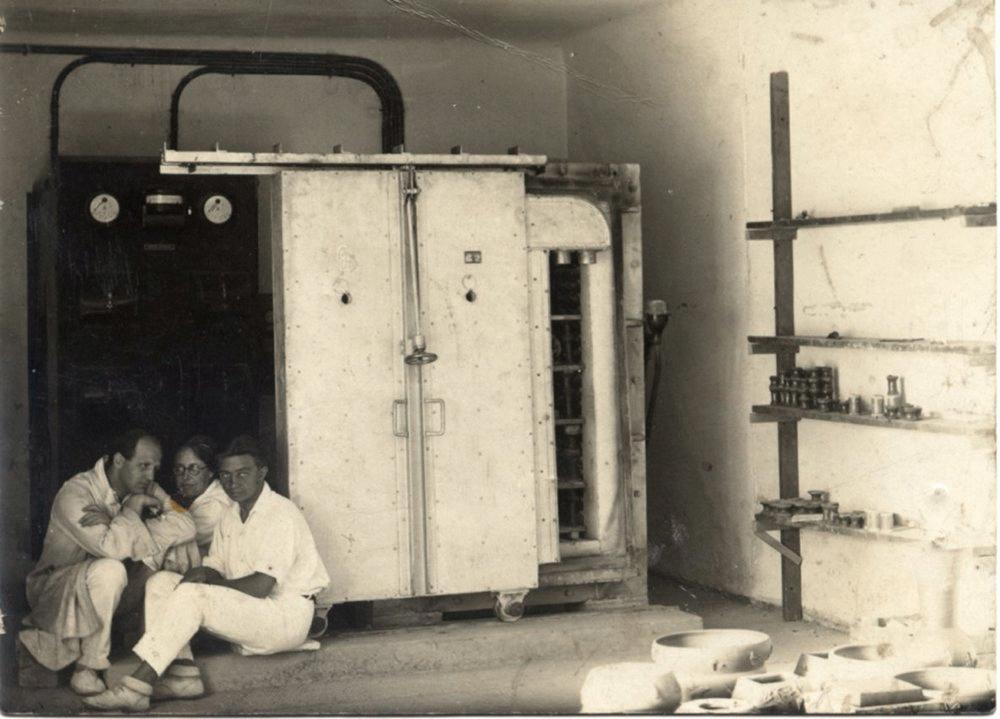

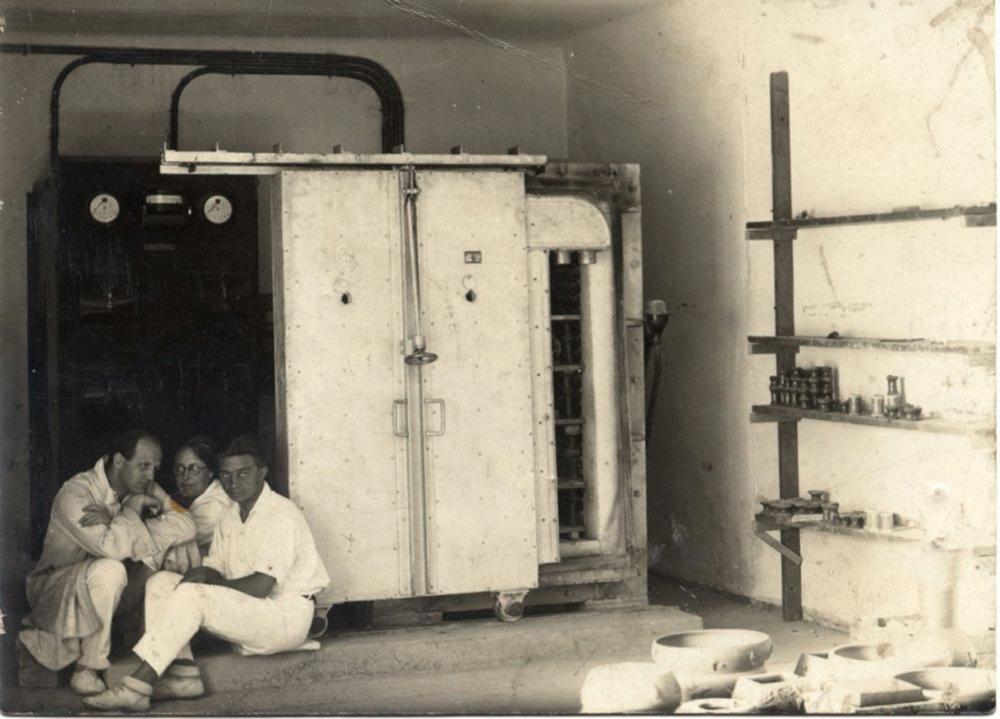

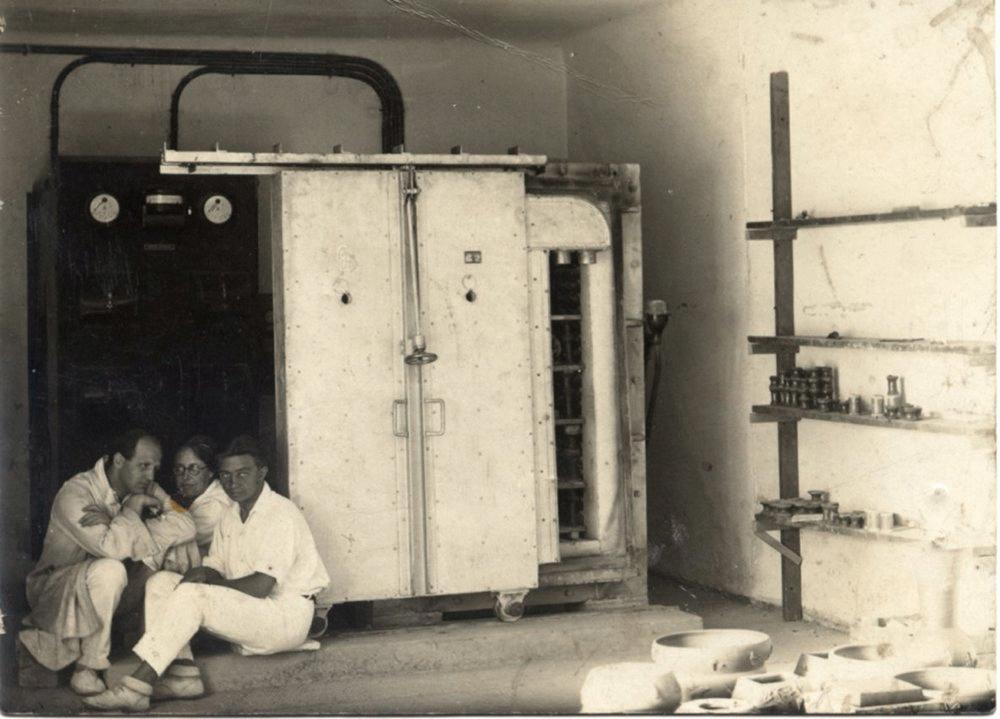

Arthur Fleischmann's art in these years was much less outspoken. It was indeed not political at all. One of the things which unites all three of our sculptors was an interest in terracotta and baked clay sculpture in general. In the case of both Herkner and Fleischmann this could include coloured glazed ceramic. Terracotta was something which Charoux only came to relatively late, shortly before he departed for England in 1935, and Fleischmann would tell how it was in his kiln that Charoux had made some of these early experiments. The uses to which Charoux put the medium were very different. His sculptures were never glazed as far as I know, and at all times, in their visual austerity, seem headed in the direction of the use he later made of cement mixed with iron powder.

|

|

|

Arthur Fleischmann with a kiln and assistants.

|

|

|

Lovers (terracotta) by Siegfried Charoux, 1935.

|

|

|

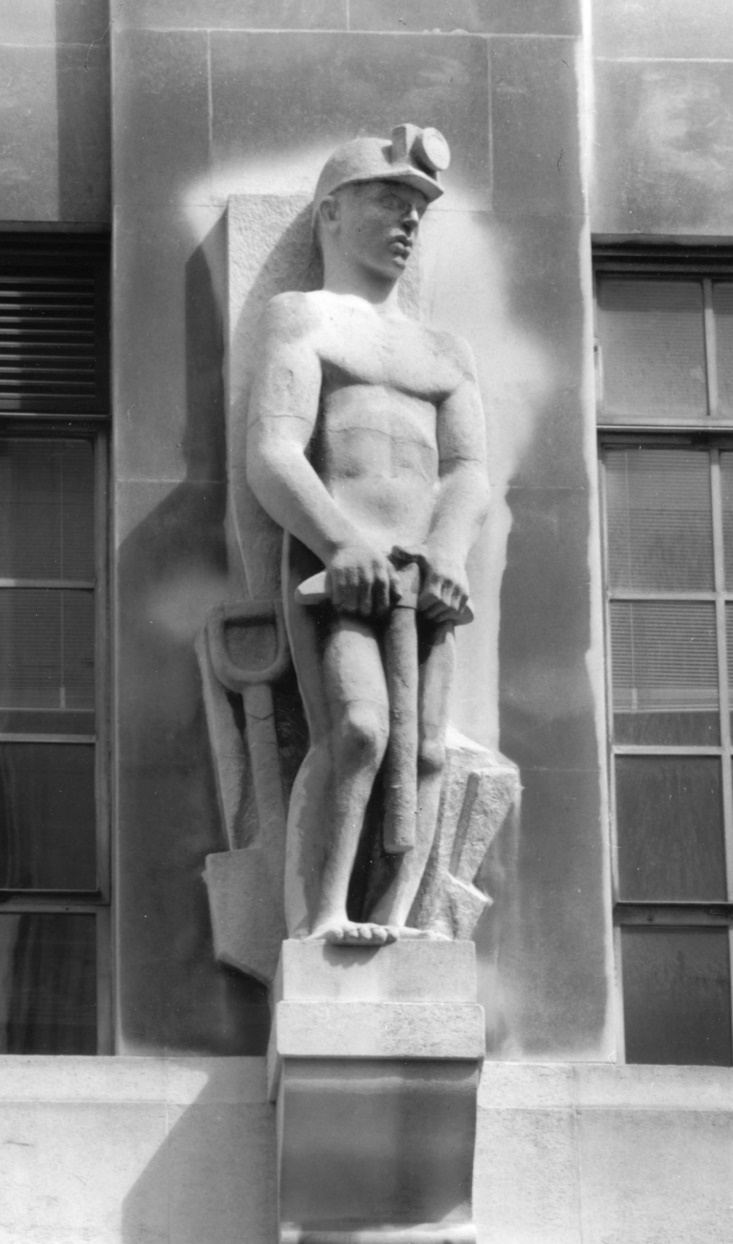

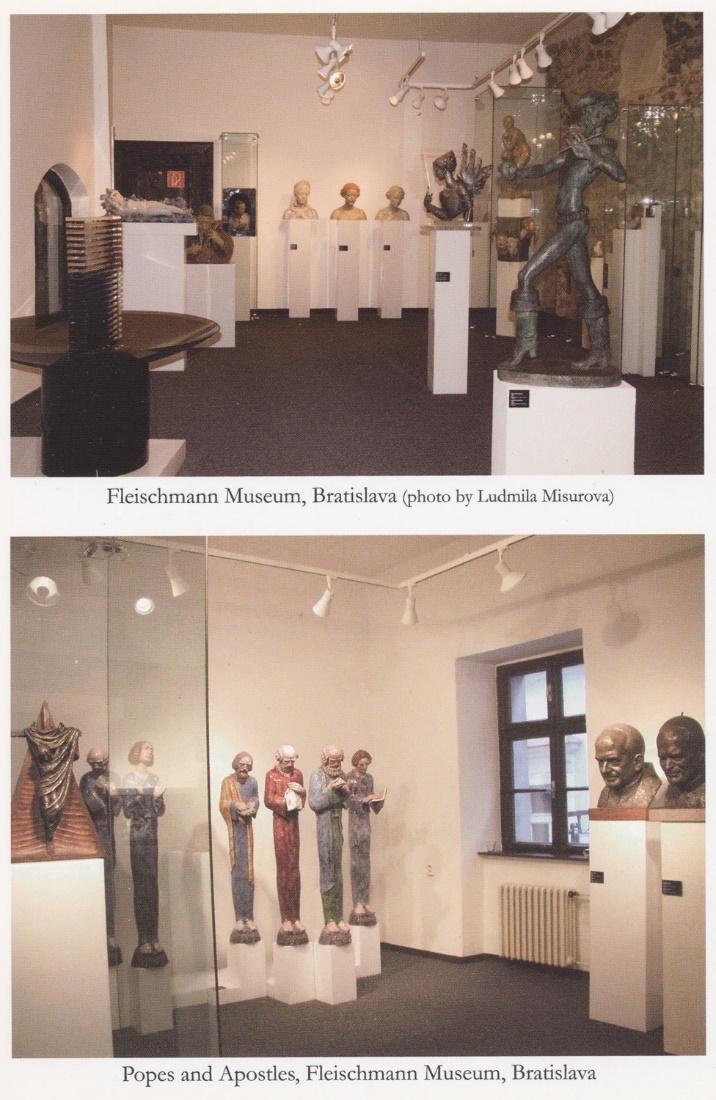

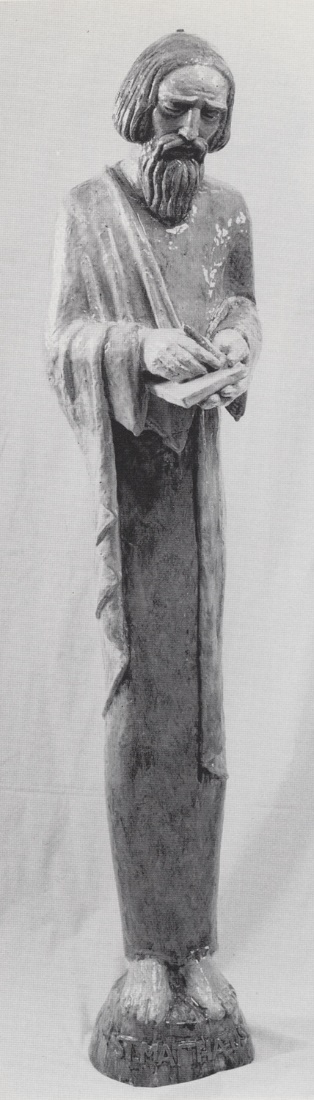

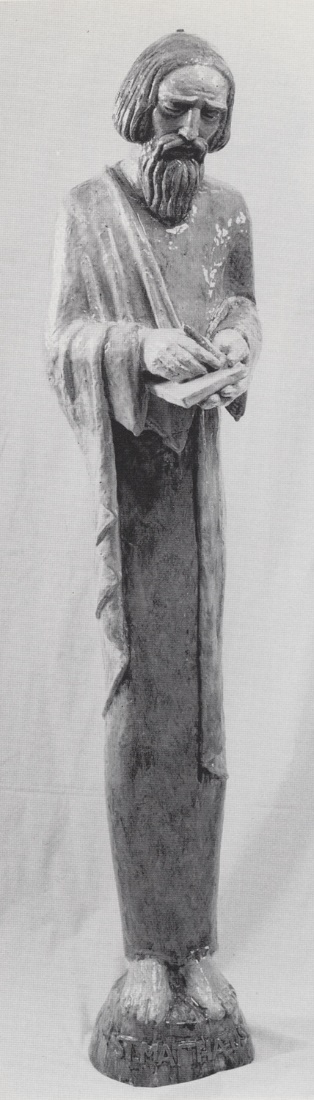

From the start Fleischmann's work was more rooted in decorative arts and handicrafts traditions. Even when later he took up plastics, his use of them brought back memories of the amber and rock crystal, which had been used earlier for altar furnishings and virtuoso tableware. Unlike Charoux, Fleischmann never eschewed prettiness or idyllic subject matter. Between 1934 and 1937, the period in which Charoux was falling spectacularly foul of the new authoritarian regime, Fleischmann taught ceramics in the Vienna Womens' Academy. At some point also he attended woodcarving classes in a traditional centre of this craft, Graz. Although only officially becoming a Catholic convert in Bali in 1939, in the early 1930s religious and biblical subjects constituted a large element in his output. It was an area in which Gothic, including elements of medieval grotesquery, as well as Baroque traditions were revived and given a new expressionistic or even at times a mechanistic slant. There is an element of mechanical serial production in the tall, coloured ceramic Apostle figures for the altar reredos in Dominikus Bohm's church in Hagen in Westphalia, where the legs and trunks of the figures appear to have been pressed out in the same mould, to create a mesmeric overall effect.

|

|

|

Church of Saint Elisabeth, Hagen (arch: Dominikus Bohm) 1929, A view of the choir and reredos with Apostles by Arthur Fleischmann, 1930.

|

|

|

Arthur Fleischmann, Apostles (glazed ceramic) 1930, for Hagen.

|

|

|

The one great achievement of the socialist local government in Vienna was its prodigious response to the city's housing shortage. The Gemeinde Wien apartment blocks and estates became the envy of the world, not least because of the imaginative integration of sculpture into them. The architect Michael Rosenauer, who had worked on these projects, came to England in 1928 and was consulted by the LCC. During World War II, he took his message to the States. After the war Charoux was an early favourite for the job of creating the frieze on Rosenauer's best known London building, the Time Life Offices in Bond Street, but of course it was Henry Moore who got that job in the end.

|

|

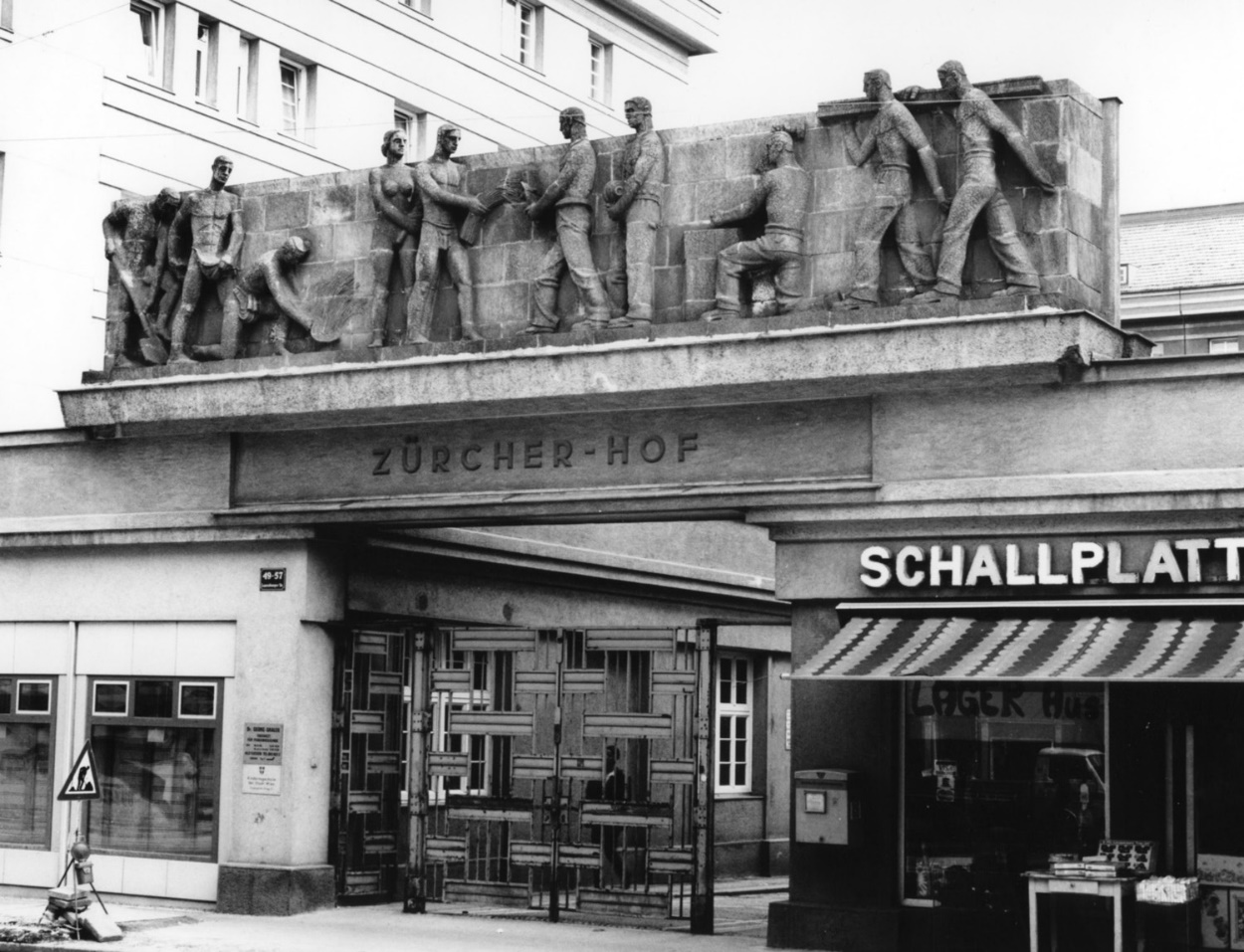

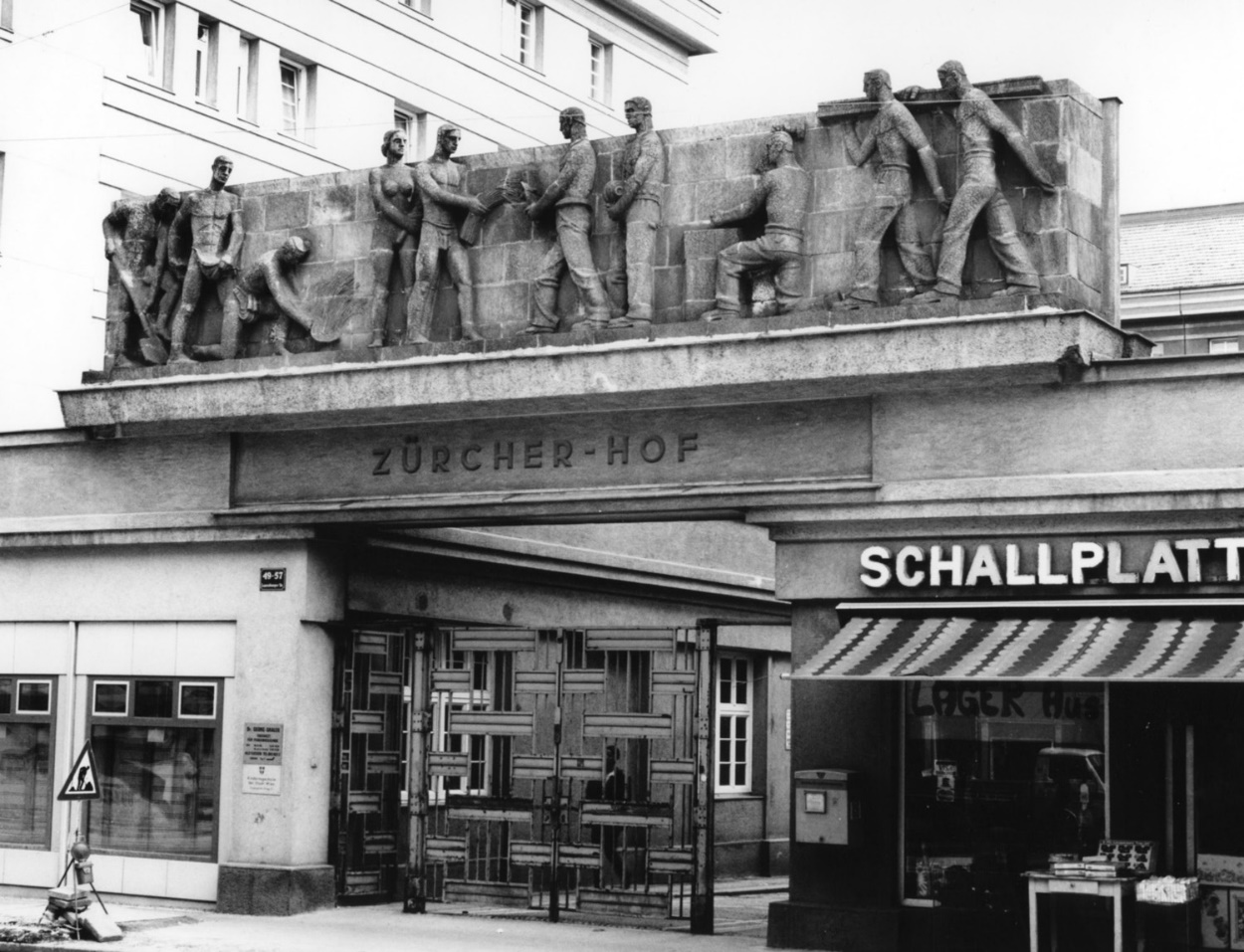

There could hardly be a greater contrast between the approaches to the decoration of the Vienna apartment blocks than those of Charoux and Fleischmann around 1930. Charoux's Workers Frieze on the Zarcherhof would have shamed any resident on the estate who was not pulling his weight in the labour market. Fleischmann's glazed terracotta frieze on the Hickelgasse residential block, on the other hand, is a timeless idyll of happy, young, all-but-nude families, going the full length of the block in celebration of leisure. Well, perhaps one doesn't come home to be reminded of work.

|

|

|

Siegfried Charoux , Frieze of Work, 1931, Zarcher-Hof, Vienna.

|

|

|

Arthur Fleischmann, Frieze with Families (terracotta) 1931, Hickelgasse Apartments.

|

|

|

So when and why did each of these three sculptors leave their homelands? Charoux was the first to go. Before the destruction of his Vienna monuments, he claimed that he had already been boycotted, after declining to accept a commission to sculpt a memorial to policemen killed by workers in riots protesting over the abuse of the constitution. The commemoration was to consist of a figure of St Michael overcoming the dragon of discord. St Michael was the patron Saint of the Austrian police and the commissioner at the time was someone called Michael Skudl. This all sounds like a provocation, a red rag to the red cat. In any event, Charoux left for England shortly afterwards, in Autumn 1935.

|

|

Arthur Fleischmann did not leave until 1937. He must have seen the writing on the wall. He had already visited Paris on a couple of occasions in previous years, and seems to have gone there again in early 1937 when the International Exhibition was underway. This featured the now famous, or infamous confrontation between the German and Russian Pavilions. Fleischmann, added to his other talents was an exceptional photographer, and on this occasion he took a picture recording the scene. He would not have forgotten that the author of the group in the foreground, Kamaradschaft, had come from the same stable as himself . Josek Thorak had been a pupil of Mullner between 1910 and 1914. Facing Thorak's group was Vera Mukhina's pair of heroically advancing workers, waving aloft he a hammer and she a sickle.

|

|

|

Arthur Fleischmann photograph of the German and Russian Pavilions at the 1937 Paris World Fair.

|

|

|

Fleischmann's escape, if that is what it really was appears to have been opportunistic and unplanned . In that same year he accompanied the Slovak football team to South Africa, in his capacity as a doctor. The following year, 1938, he accompanied some friends from South Africa to Bali, and was so taken with it that he stayed on until a threatened Japanese invasion persuaded him to leave for Australia. It cannot be said that at this point Bali was an undiscovered island paradise. It had had many artistic visitors, especially Dutch painters and people interested in the traditions of Legong dance. In the previous year the American anthropologist Margaret Mead was there with her English husband Gregory Bateson observing and filming Balinese mothers rearing their children. And yet, for Fleischmann it remained an island paradise, full of beautiful women and people who managed to get on with their lives impervious to the gaze of outsiders. What a release this must have seemed from the fraught atmosphere prevailing in Central Europe just then. He was also able to put to sculptural use the open-air kilns in which the Balinese baked their kitchen utensils, and of course, while he was there, he made a marvellous photographic record of local life, and even a couple of documentary films.

|

|

|

Arthur Fleischmann, open air kiln in Bali, 1938.

|

|

|

Rmpang Going to Market (terracotta) 1938, Left behind in Bali.

|

|

|

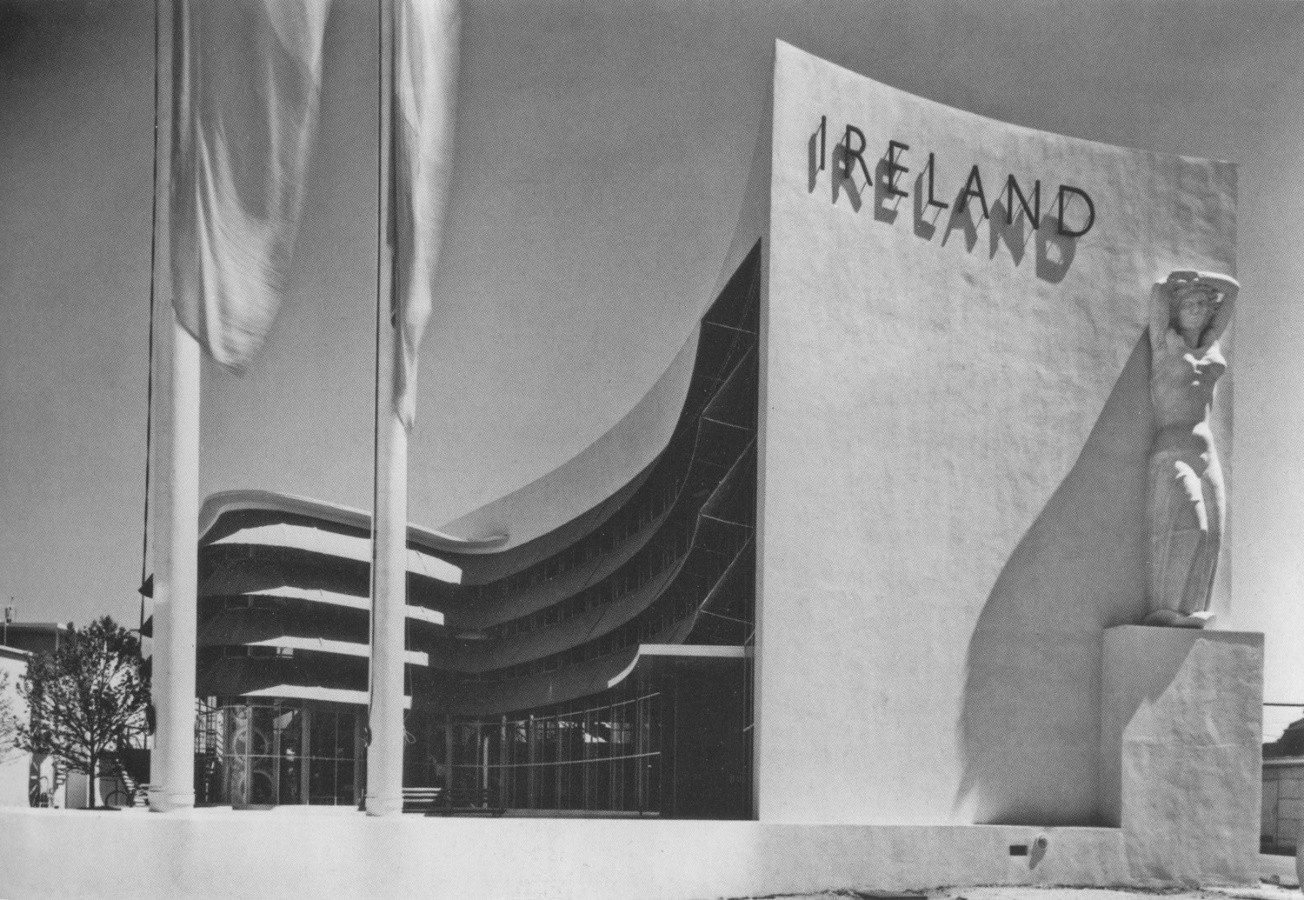

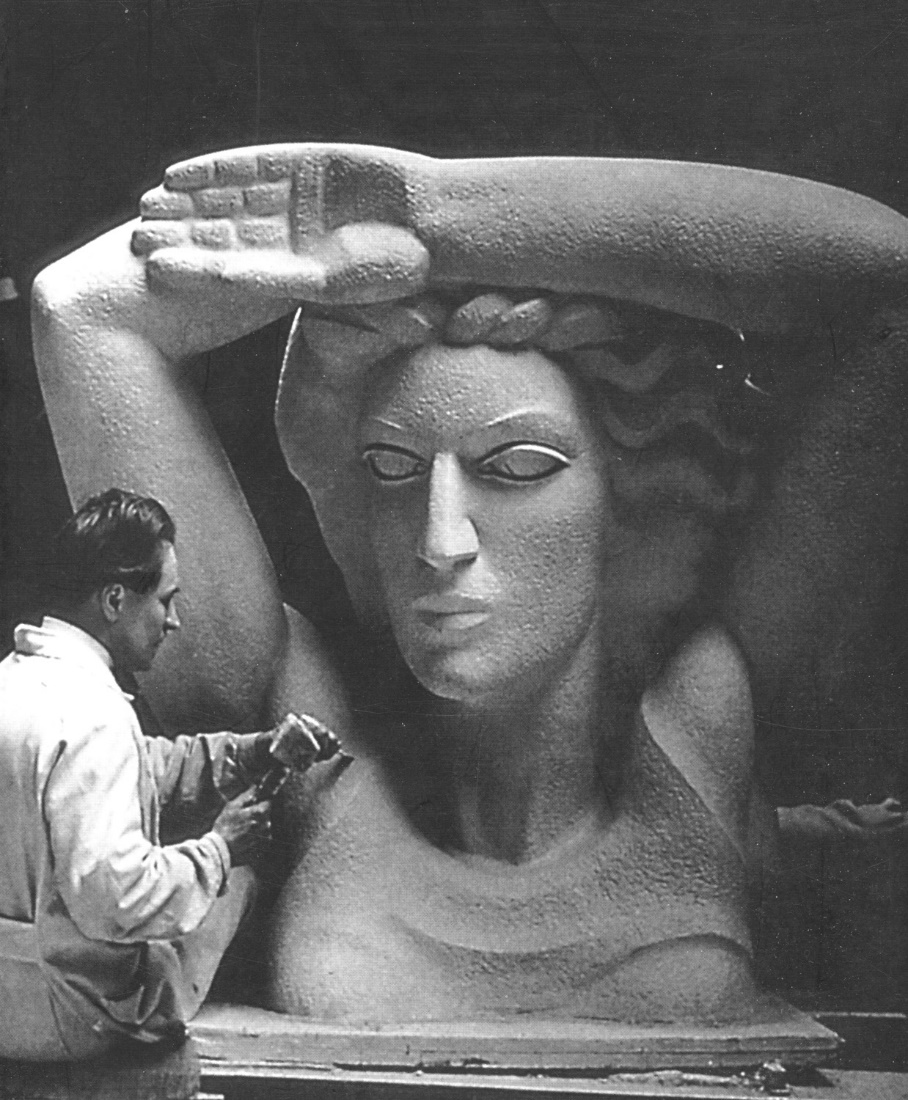

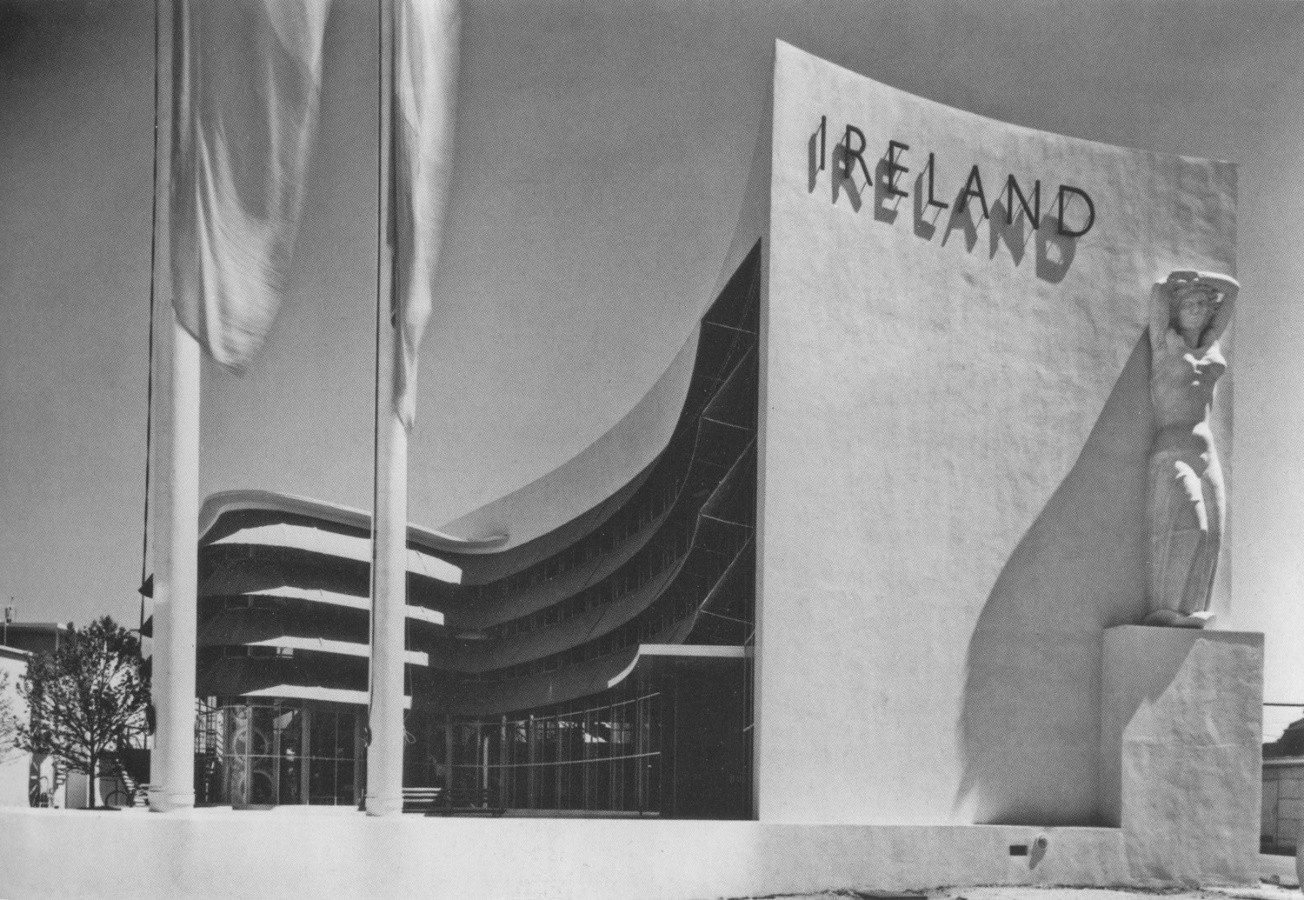

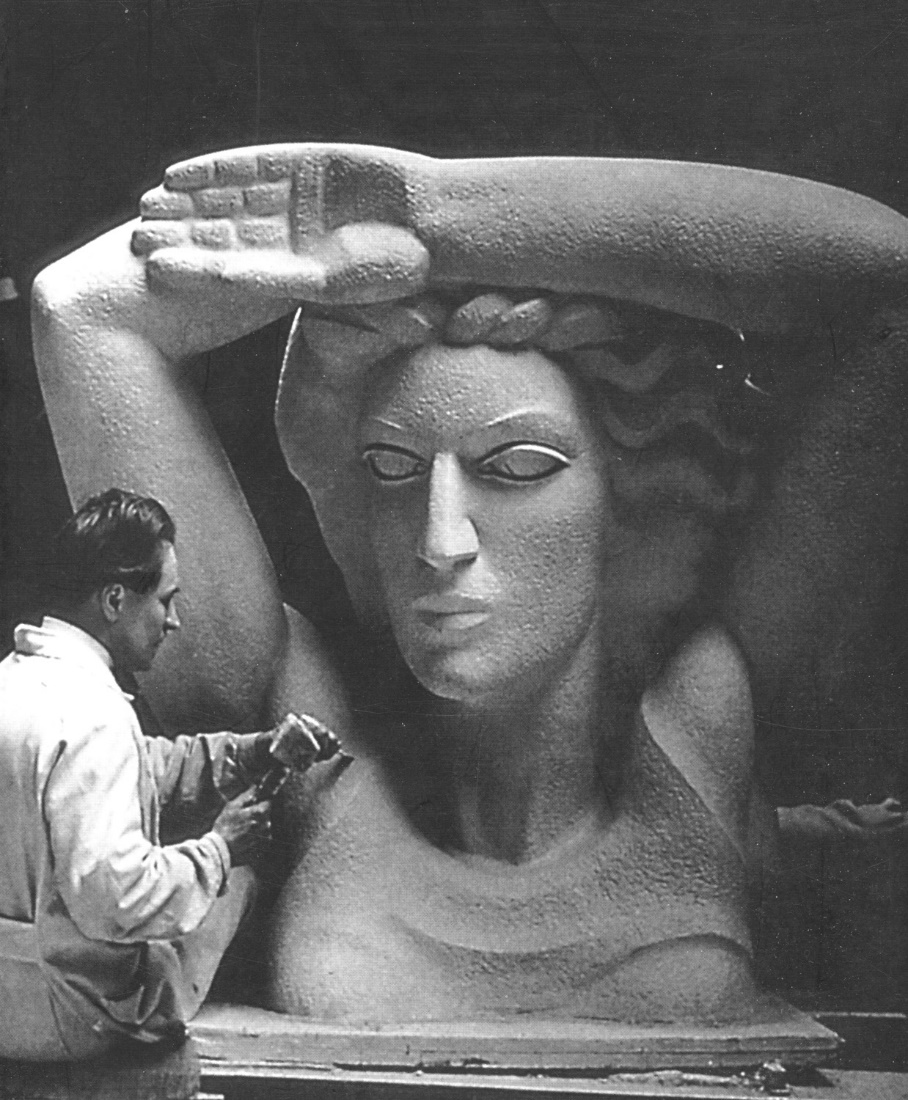

Friedrich Herkner was the last of the three to leave central Europe. In 1937 he applied for and got a post as head of sculpture in the Irish National College of Art and Design in Dublin. He began work in Dublin the following March. In the very short space of time that remained to him before the outbreak of war, he produced what remains his most renowned work, a massive figure of Eire for the Irish pavilion at the 1939 New York World's Fair. It was inspired by words from a W.B. Yeats poem entitled Into the Twilight, and in particular the words 'in a time outworn ... your mother Eire is always young'. There seems little enough of Celtic Twilight about either Herkner's sculpture or Michael Scott's very modern pavilion, though, unless seen from the air, it was not possible to make out that the ground-plan took the form of a shamrock. Herkner's figure was said to express 'the magnificence of a nation reborn'.

|

|

|

Irish Pavilion at the 1939 New York World's Fair (arch: Michael Scott), with Eire by Friedrich Herkner.

|

|

|

Irish Pavilion at the 1939 New York World's Fair (arch: Michael Scott), with Eire by Friedrich Herkner.

|

|

|

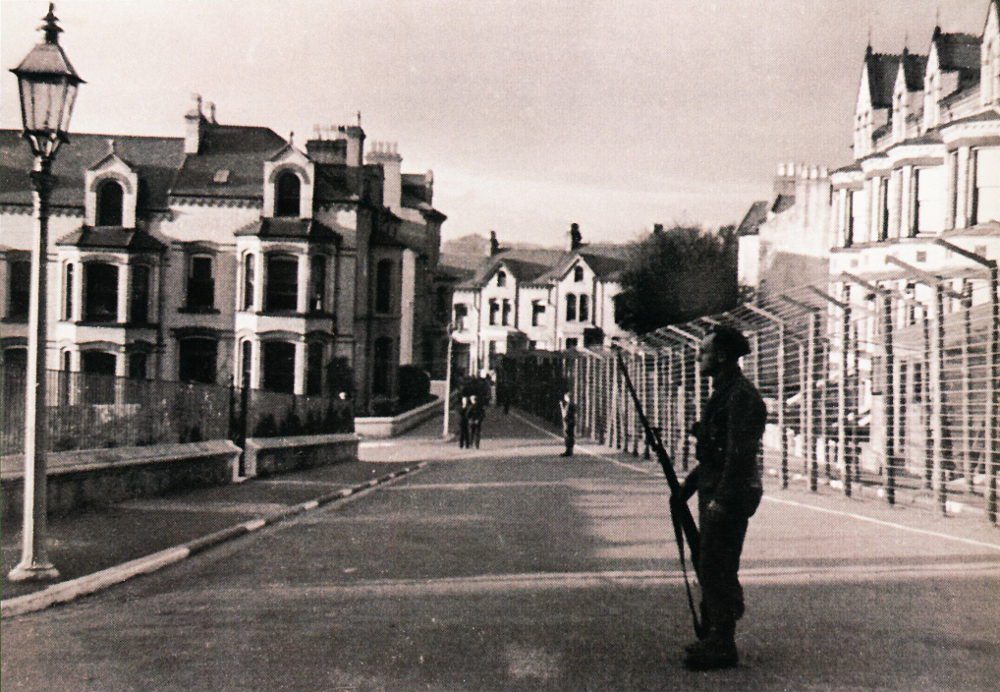

And then came the war. How did the three sculptors fare in this time, and what kind of a war did they have? Amongst them Herkner was the only active combatant. Slightly younger than the others, he had missed out on service in the first World War, but in this one he enlisted for the German army and served on the Russian front. Ireland famously retained its neutrality, and clearly there would not have been any pressure on Herkner to go. It was probably the fear that if his employment in Ireland did not hold up, he would be left high and dry if he were, in effect, to desert. He ended the war as a prisoner of the Russians in Berlin, and was unable to return to Ireland until 1947. In the interval he was employed restoring damaged sculpture in Heidelberg and Vienna.

|

|

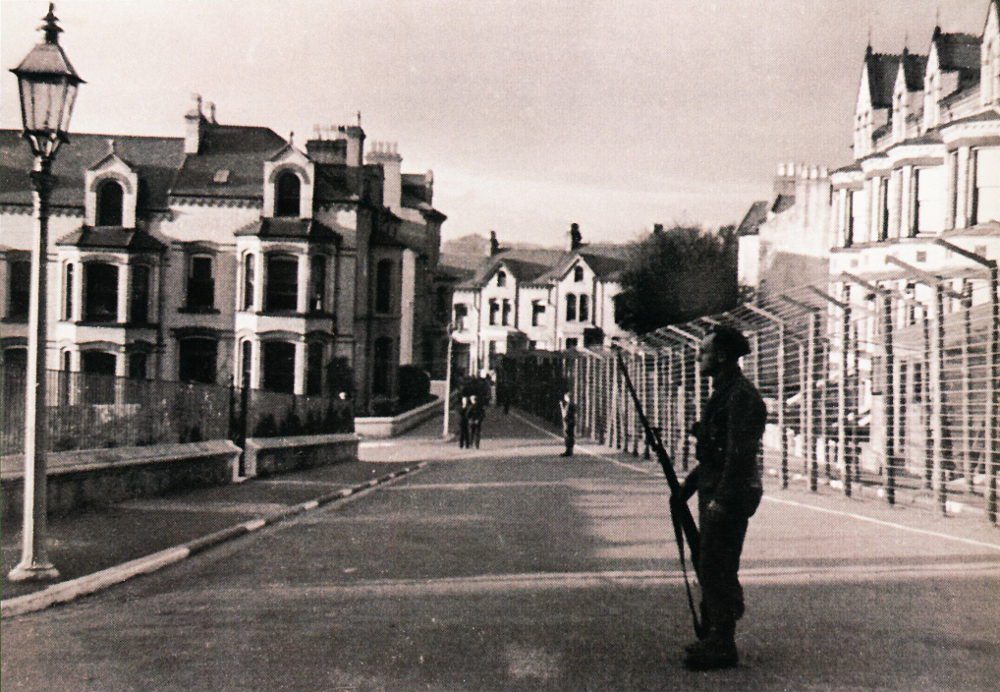

For Charoux, England had been slow to extend a welcome. From 1938 he was able to join the Free German League of Culture and the Austrian Centre. I'm also pleased to be able to say that my uncle by marriage, John Murray Easton of the architects Easton and Robertson gave Charoux work, though of a rather modest kind, on the Anatomy and Engineering Department buildings at Cambridge, starting as early as 1937. 1940 was a very mixed blessing for him. For the first time he had work accepted by the Royal Academy, but later in the same year he found himself interned as an enemy alien in the Hutchinson Square Camp in Douglas on the Isle of Man, alongside Kurt Schwitters and his brother and the sculptor Georg Ehrlich. There were a number of such camps on the Isle of Man, but most of the creative types seem to have ended up in this one, supervised by a British officer, whose previous job had been as housing manager at the Dolphin Square apartments in London. The incredible art activities of this camp, in reality a number of converted holiday boarding houses, have been recounted by Klaus Hinrichsen, a German art-historian who was another of the interns. I will keep back one of my wilder theories about the influence of these activities till later, since it hinges on the resumed friendship of Charoux and Fleischmann post-War. Charoux was one of the signatories of a letter addressed to Sir Kenneth Clark from the camp, asking him to use his influence with the Home Office to extend to artists the right to apply for release. It was hardly acknowledged in the original White Papers on this subject, that artists might make as useful a contribution to the war effort as scientists and engineers. Both of the works which Charoux exhibited at the R.A. in 1940 were in terracotta, and such works would soon excite critical interest because of the way he constructed them, using internal clay struts to support unusually large hollow forms.

|

|

|

Sentry duty, Hutchinson Camp.

|

|

|

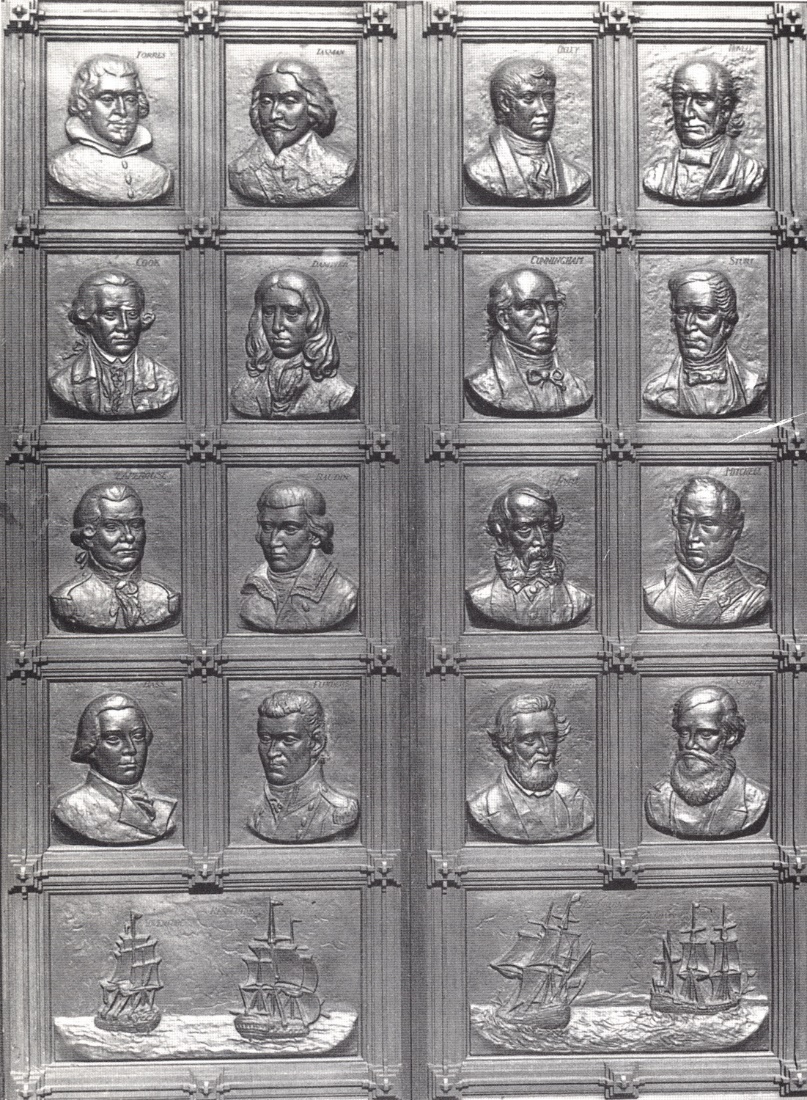

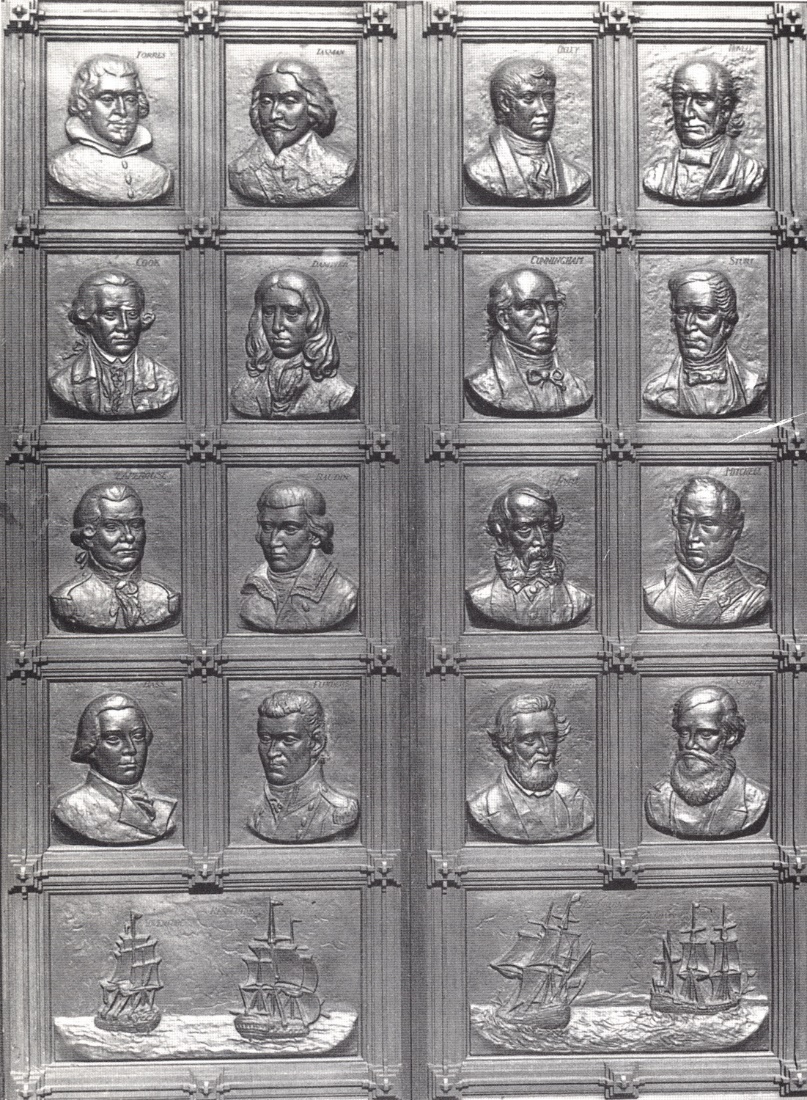

With the outbreak of war, but some time before the Japanese invaded the Dutch East Indies, Arthur Fleischmann left for Australia, settling in Sydney in 1939 and immediately becoming a naturalised Australian subject. He was also elected very swiftly to the Australian Society of Artists. He found many patrons in the country, and the Fleischmann family to this day continue to receive news of newly identified devotional sculptures commissioned for Australian Catholic churches of which they previously knew nothing. The 1941 inauguration of his Explorers Doors for the State Library of New South Wales confirmed his credentials as an Australian artist. Indeed this was what he remained, and even far into his English period he continued to be referred to as 'the Australian sculptor Arthur Fleischmann'. If a commission like the one for the doors looked as though it might be turning him into a pillar of the establishment, an attraction to the bohemian life manifested itself in his becoming a founder member of a group brought together by an art-loving landlady, Chica Lowe, in her villa in the Sydney suburb of Woolahra. In the photographic portraits taken by its photographer member, Alec Murray, the Merioola artists, who took the name of Chica's home as their monicker, look as if they've stepped out of a Rene Clair movie. Dancers and scholars even were included in their number. They were renowned for their attempt to remain light at heart, and to forge ahead with their activities regardless of the war. Most importantly perhaps for his future development, Fleischmann started using plastics for his sculpture, at this stage cast phenolic resin, which came out looking rather like amber.

|

|

|

Arthur Fleischmann, High Caste Brahmin Priest (terracotta) 1938. Left behind in Bali.

|

|

|

Rmpang and Runding returning hom from the rice-fields (bronze) after 1938.

|

|

|

Arthur Fleischmann, Explorers Door (bronze) 1941, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney.

|

|

|

The Merioola Group, photographed by Alec Murray.

|

|

|

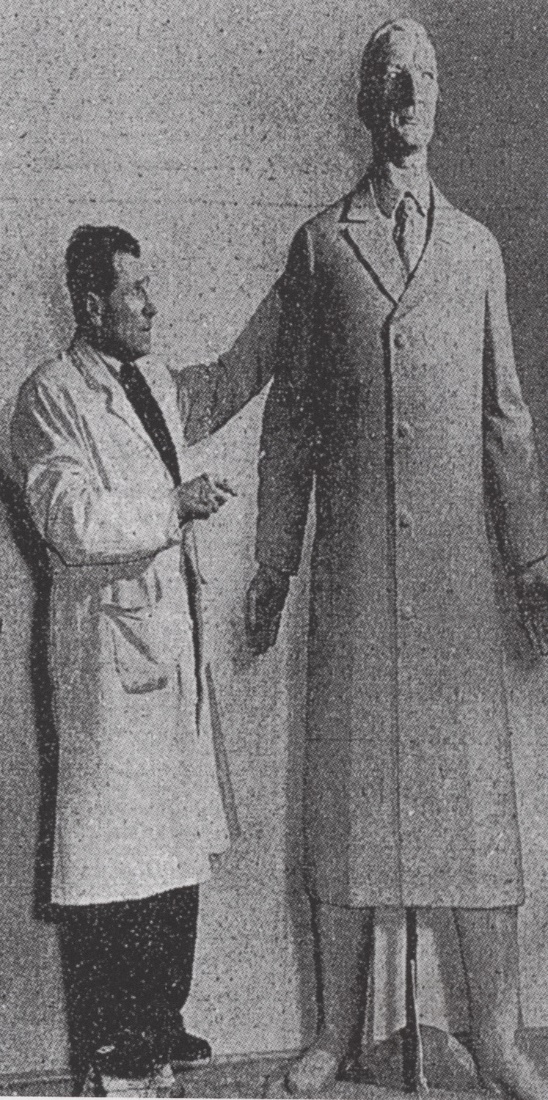

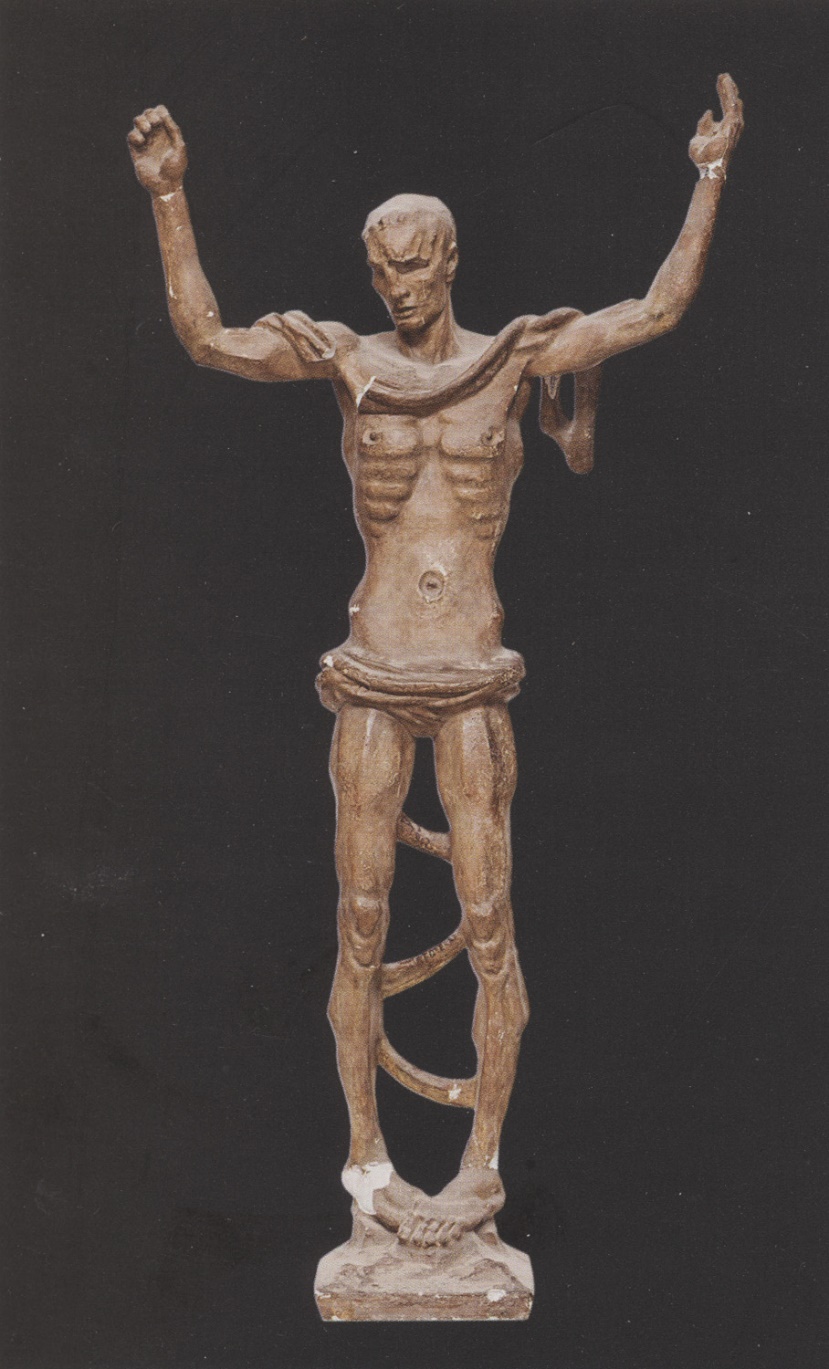

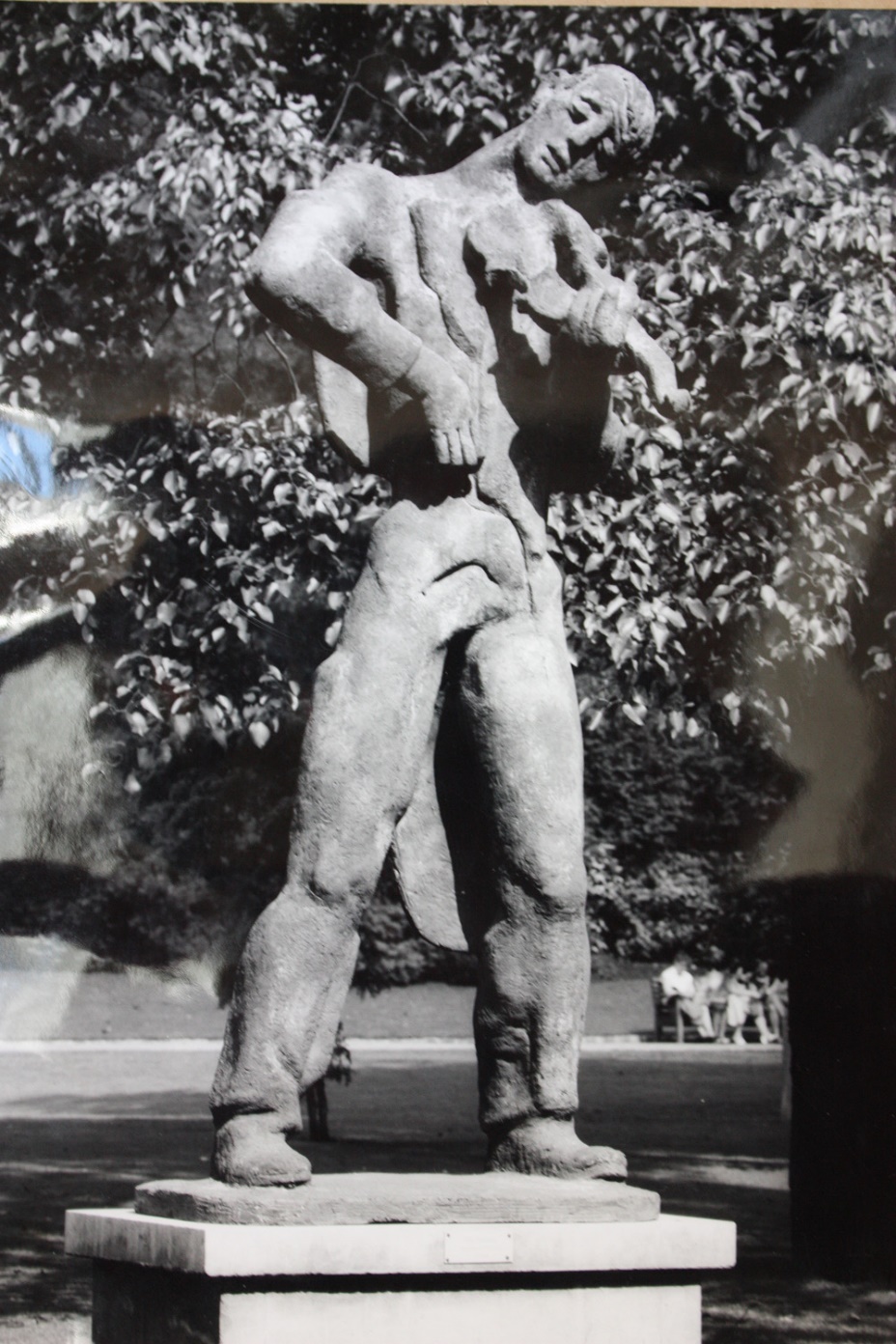

Siegfried Charoux, by virtue of having been here throughout the war was thoroughly embedded in the British art world, by the time the two others made it back to Europe. He was on friendly terms with a number of RAs. He was getting substantial notice in the press, and was welcomed as a visitor to the RA Schools, because of the experience he had gained with large scale terracotta sculpture. Herkner's return to Ireland was delayed by difficulties obtaining a passport, but he was finally asked back in 1947. He returned, in his own words, 'as poor as a beggar'. Though he was a beneficiary of Eamon De Valera's even handed policy towards the different participants in the recent conflict, some other members of staff at the college in Dublin took offence at having to work with him. One English sculptor instructor refused to return to the college, and there was a permanent stand-off with a very talented Dutch graphic designer, who was on the staff. Long term however, many of his Irish students had very affectionate memories of him. His 1952 entry for the ICA's Unknown Political Prisoner competition was one of only two Irish entries to get through to the second round. It expressed, he said, his feelings about the war, and is a kind of secular crucifixion, with the stylised anatomy found in some medieval German and Italian crucifixes. With similar stylisations, Herkner did a great deal of devotional sculpture for Irish Catholic churches. His being of the faith will have been an added qualification when he first applied for his job in 1937. Once back in his post, Herkner found himself having to implement a recommendation by Thomas Bodkin that the ceramic facilities at the college, which had fallen into disuse, should be revived, something he was especially well equipped to do, though his interest in ceramics is said to have remained exclusively sculptural.

|

|

|

Friedrich Herkner with his colossal figure of De Valera (ciment fondu) 1958.

|

|

|

This Tragic Age (glazed clay) 1952, Dublin, Royal Hibernian Academy.

|

|

|

It seems that when Arthur Fleischmann came to England in 1948 it was not with the intention of staying permanently. For ten years he lived and worked in a series of rented properties. However, in 1955 he married Cecile Joy Burtonshaw and three years later they moved into what had been the purpose-built studio of the sculptor Sir George Frampton at 92 Carlton Hill. Joys tells me that she thinks her husband saw more of Charoux in the years before they were married than he did later. In his first two years in England, he showed Balinese subjects at the Royal Academy. The Festival of Britain in 1951 was a big opportunity for both Charoux and Fleischmann, but as with their contributions to the Vienna housing projects, their response could hardly have been more different. Charoux's very prominent contribution was the gigantic stone relief called The Islanders on the front of Basil Spence's Sea and Ships Pavilion facing the Thames on the main South Bank site. This was Charoux's heart-warming tribute to the host nation. I can't help wondering whether he was thinking of Herkner's 1939 Eire when he produced this image, but have no certain knowledge that Herkner was ever in his thoughts. It seems a last, perhaps justifiable, flourish of a patriotic rhetorical mode soon to disappear in Western Europe. There were many other memorable sculptures on the main site as we all know, but there seems to have been general agreement that they were all, including the Charoux, rather upstaged in the popular imagination by an architectural monument, the Skylon, designed by Philip Powell and Hidalgo Moya. This was, as Margaret Garlake has said, 'an apt symbol of the unknowable; it was everyone's future and the vehicle of every space odyssey'. Bearing in mind that Arthur Fleischmann would later collaborate with Powell and Moya for Expo 70 in Osaka, I asked Joy whether there was any likelihood that the experience of the Skylon had set that particular ball in motion. She and he did go to the Festival together, but apart from it being the sort of celebration of technological progress that he admired, her answer suggested that my supposition was more fantasy than fact.

|

|

|

Siegfried Charoux, The Islanders (stone) 1951.

|

|

|

The Skylon, arch: Powell and Moya.

|

|

|

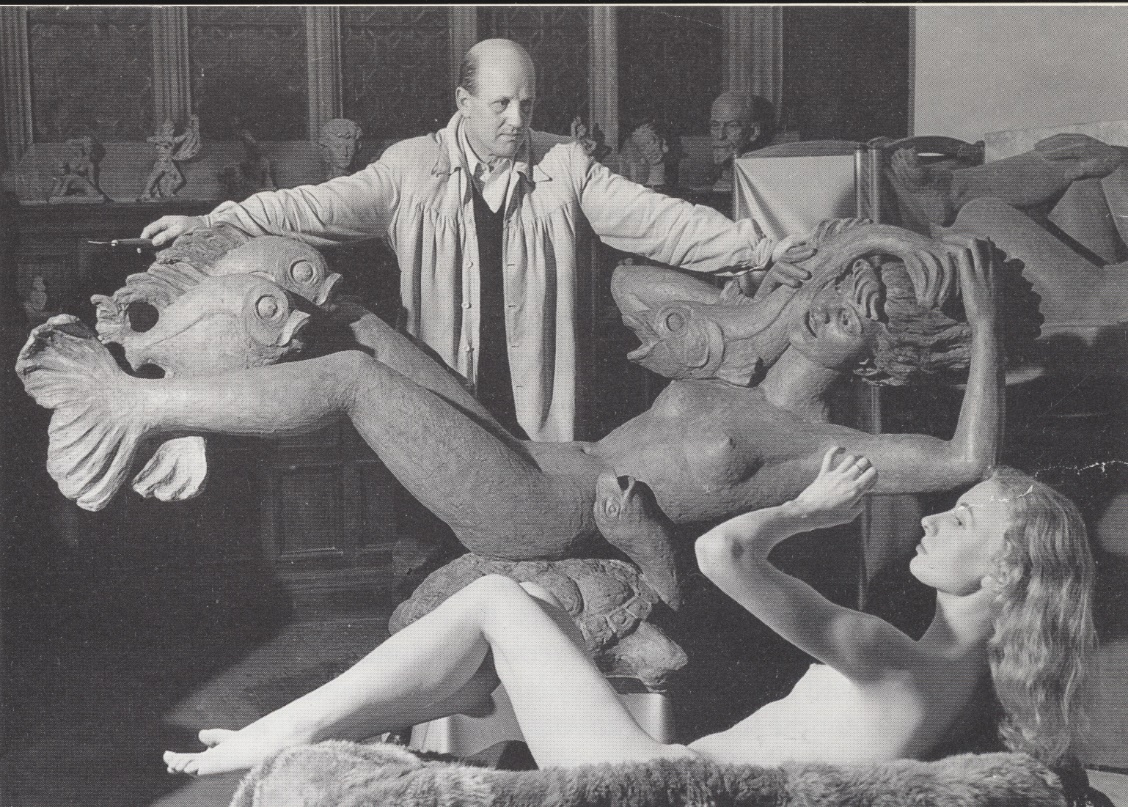

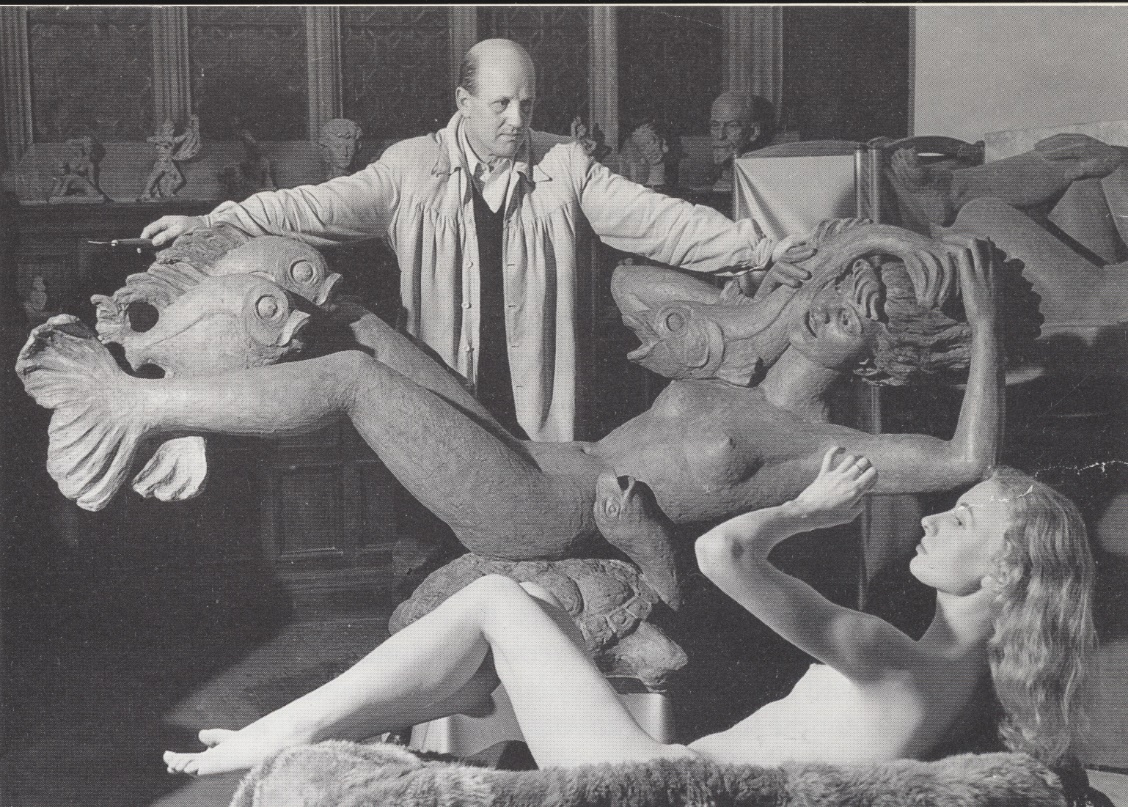

Fleischmann's more modest contribution to the Festival of Britain, was for the Battersea Park festival site, where fun and entertainment were the priority and where private sponsorship footed the bill. His bronze fountain figure sponsored by Lockheed Engineering was called Miranda the Mermaid. This Miranda was not Prospero's daughter from the Tempest, nothing so grand or literary. She was a mermaid from a recent popular film, its title role played by Glynnis Johns, in which a doctor on a fishing holiday inadvertently catches this flirtatious siren on his hook. Like any baroque sculptor from Central Europe, Fleischmann felt perfectly at liberty to reinvent her finny extremities as he thought fit, though the style is far more American deco than baroque. The mermaid in the film, when in London, has to be carried around with a blanket over her tail, as if she were concealing a disability.

|

|

|

Arthur Fleischmann with Miranda and model (press photograph) for the Festival's Battersea Park Site.

|

|

|

During the 1950s Fleischmann found himself an entirely new artistic seam to explore. It was one which was both new and untried, and yet reminiscent of older craft traditions of a kind which might be described as sumptuous, even showily magnificent. If one takes Charoux's progress from unglazed terracotta to ferrous cement as in some ways symptomatic of post-War austerity and denial of materialism, this might have been seen as flying in the face of a modern aesthetic. However it was very suitable for two of the destinations for which it would come to serve. One was sparkling sculptural fittings for cruise-ships and the other ecclesiastical sculpture, including both devotional images and church furniture. In 1958, for example, the Whitworth Gallery in Manchester put on an exhibition of church art, which included both modern and historical work. Amongst the modern things were maquettes by Henry Moore for his Northampton Madonna and Child . Some specimens of the stained glass destined for Coventry Cathedral were the centrepiece of the show, which put particular emphasis on the variety of media used. It is easy to see how in such a context a Calvary Group in Perspex by Arthur Fleischmann might have suggested to a reporter for the Times that there were 'great possibilities for this new material'.

|

|

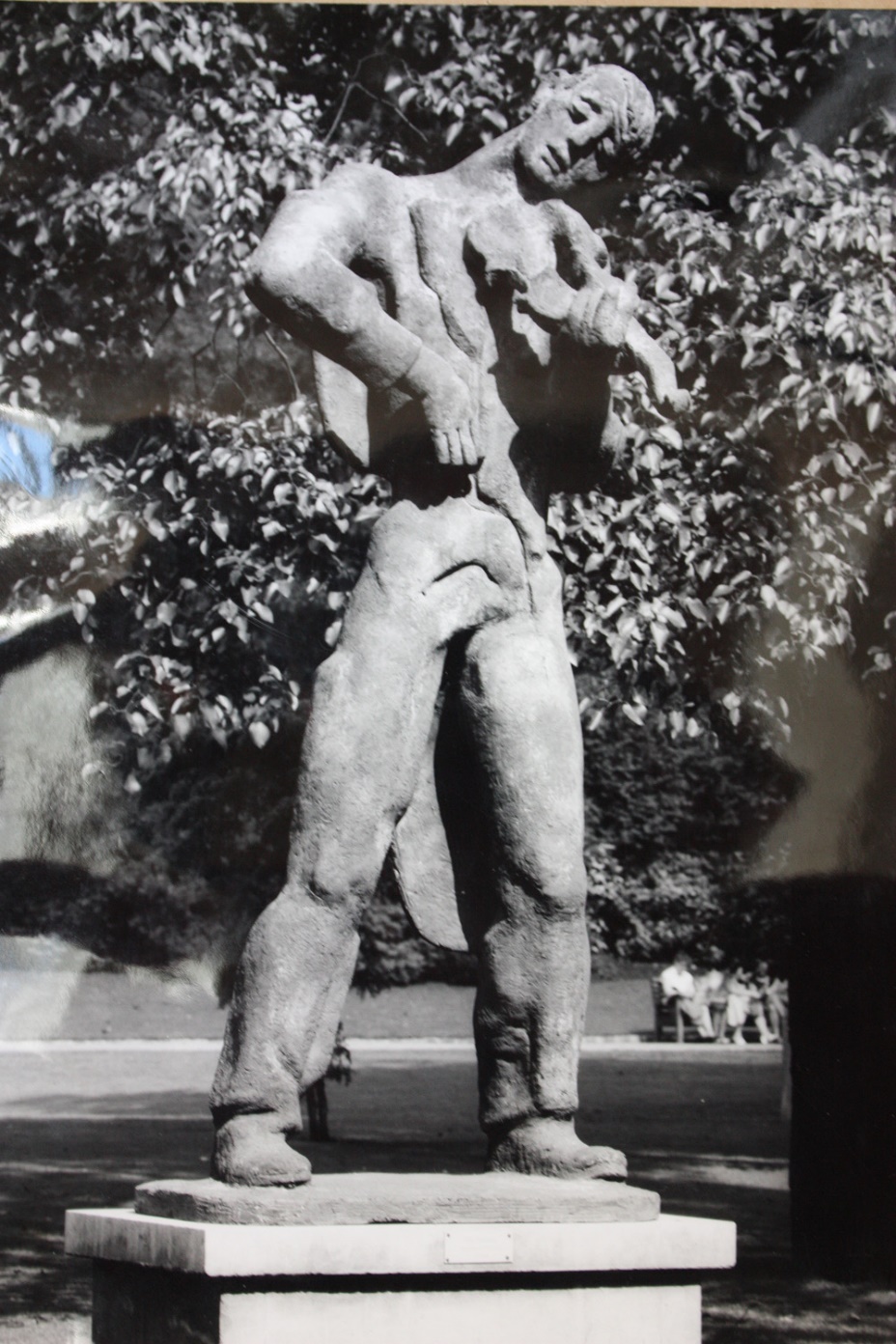

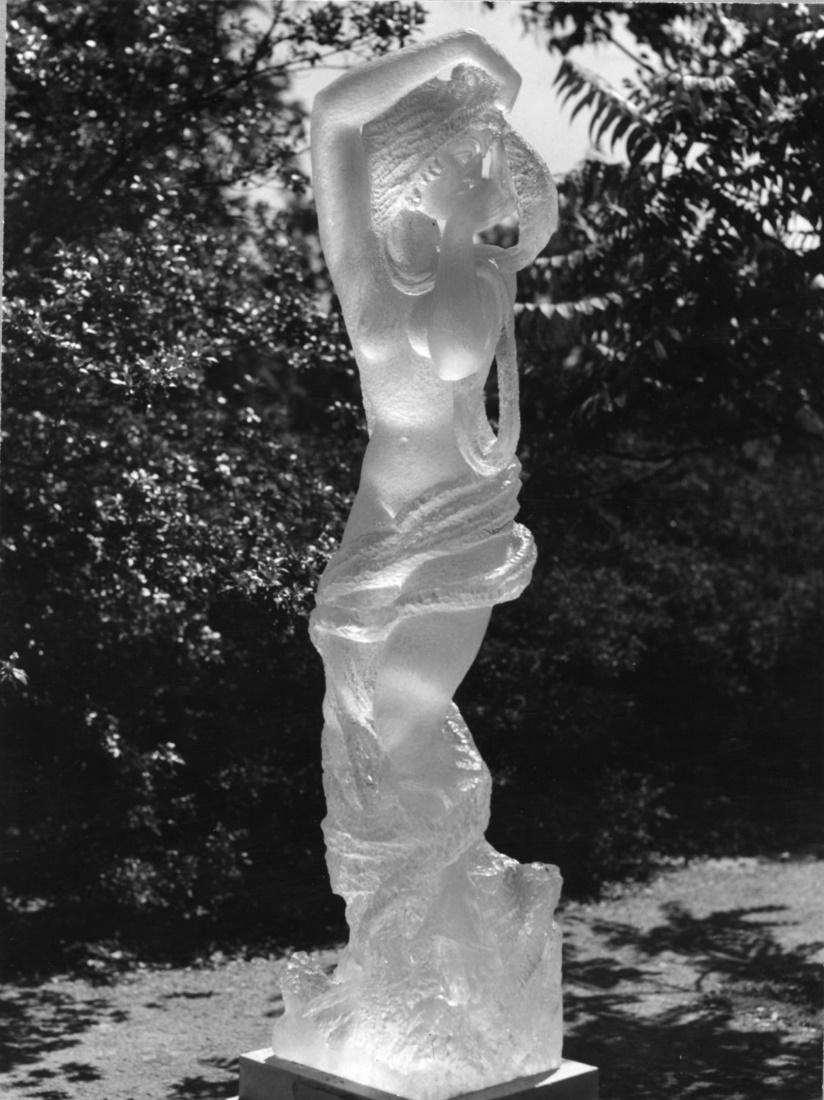

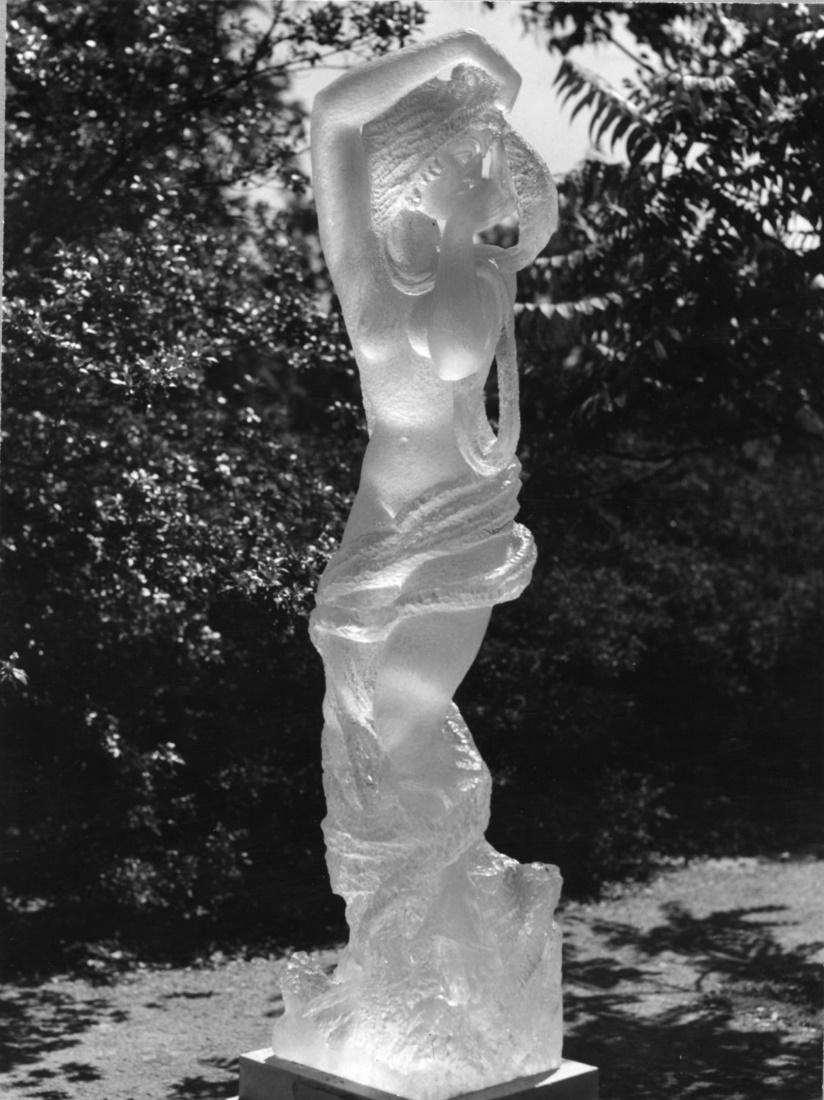

In the on-going, if at times virtual, conversation, which must have gone on between Fleischmann and Charoux I think that the perspex statue of Lot's Wife, which Fleischmann showed at the LCC's Holland Park open-air sculpture exhibition in 1957, must have carried a personal message. Probably on the strength of his British reputation, Charoux found himself being wooed by his home city, and responded by producing for Vienna new monuments to Richard Strauss and the turn of the century peace-campaigner Bertha von Suttner. In addition he produced a replacement for the destroyed Lessing statue, which was inaugurated after his death in the Judenplatz, close to where Rachel Whiteread's Holocaust Memorial now stands. Fleischmann, after becoming a permanent British resident was far from having renounced his natural wanderlust. Indeed, in his extreme old age he still proclaimed himself a roving artist, without any true homeland. The one place he does not seem to have felt any inclination to go was Central Europe. For him this became, like the Cities of the Plain, a place one should not look back at.

|

|

|

Siegfried Charoux, Violinist (cement), 1959-60, shown at LCC open air sculpture exhibition in Battersea Park 1960.

|

|

|

Arthur Fleischmann, Lot’s Wife (perspex) c.1957, shown at LCC open air sculpture exhibition, Holland Park 1957.

|

|

|

Siegfried Charoux, Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (bronze) replacement statue, 1962-65, erected Ruprechtskirche, Vienna in 1968, moved to the Judenplatz in 1981, Vienna.

|

|

|

Siegfried Charoux, Memorial to Bertha von Süttner(bronze) 1959, Favoritengasse, Vienna.

|

|

|

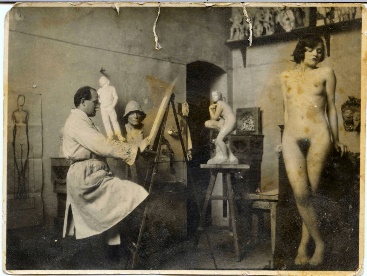

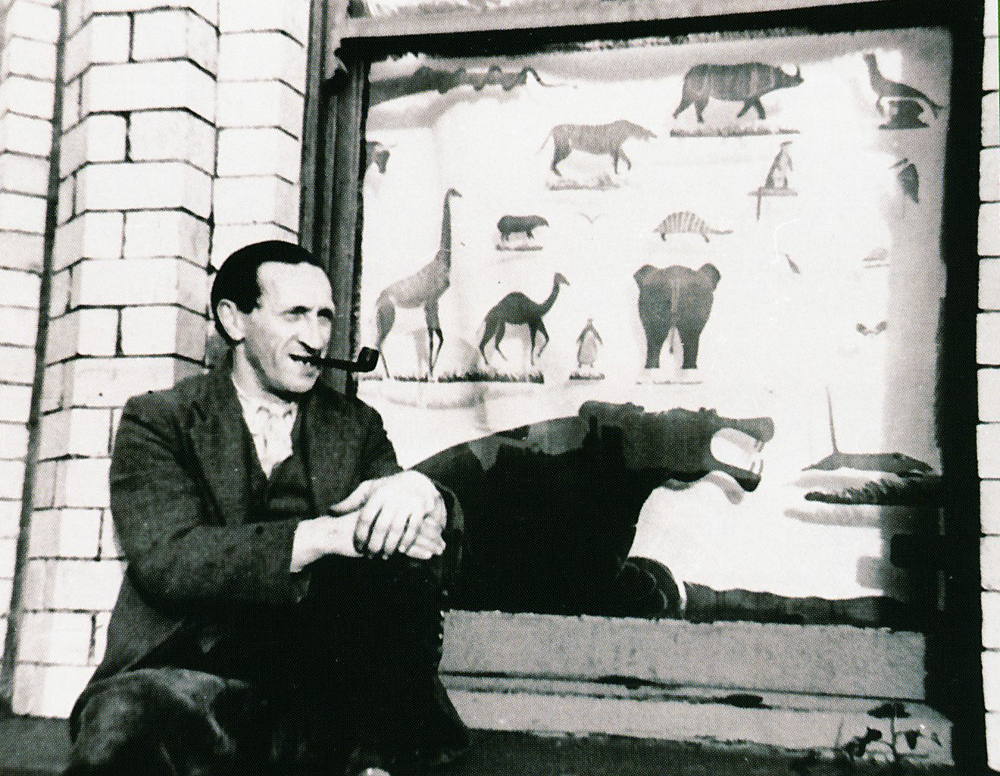

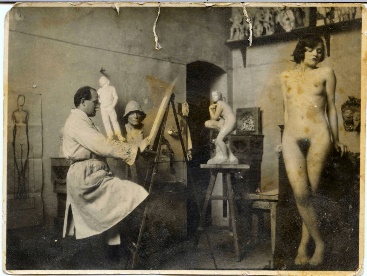

It was on the return from one of Arthur Fleischmann's travels, on a boat from South America in 1964, that he called in, with Joy and their son Dominique, on Friedrich Herkner in Dublin. They had been exchanging Christmas cards in the intervening years. Still apparently dirt poor, Herkner's answer to the suggestion that he should make them a cup of tea were the words 'cups we have'. The only other thing that Joy remembers, is that when Arthur showed Herkner two old pictures from earlier days, one showing him working in the studio with a rather pretty nude model, and the other the picture of his kiln, Herkner only said 'what a very big kiln'. Ho ho. A touching reunion nonetheless, given what had passed in the years between.

|

|

|

Arthur Fleischmann with kiln and assistants.

|

|

|

Arthur Fleischmann drawing from a nude model in his Vienna studio mid-1930s.

|

|

|

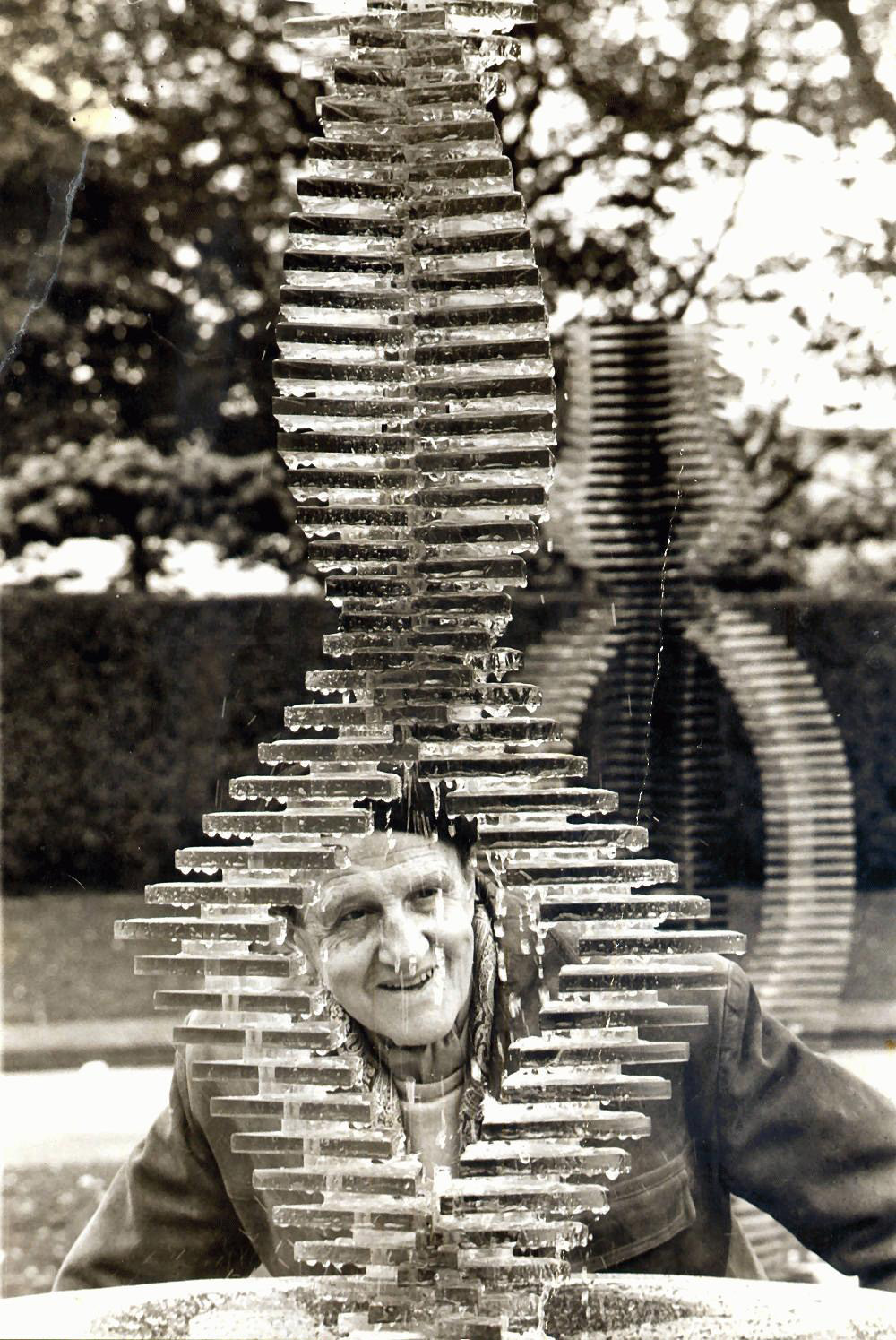

Charoux died in 1967. Herkner retired in 1969 and died in 1987. He had become an Irish citizen in 1953, when he was joined in Dublin by his German wife Lydia and their three children. Just after the death of Charoux, at the end of the 1960s, Arthur Fleischmann's art entered a new phase. He "went abstract" as we used to say about people in those days. The perspex blocks he had used for sculptures like Lot's Wife had needed to be built up from laminated slabs of the material. He decided, instead of carving it, to build up structures by layering the slabs, as they came from the manufacturer, often using coloured Perspex and incorporating water. The sculptures themselves rather resembled those being produced around this time by the 'Op' artist Michael Kidner, to illustrate chaos theory and other mathematical ideas. Shortly after moving into the field, Arthur Fleischmann got a tremendous opportunity to go public with it. This was when, through the Central Office of Information, he was commissioned to produce a water sculpture for the British Pavilion, designed by Powell and Moya of Skylon fame, for the Osaka 1970 Expo. The exhibition, which had been masterminded by the Japanese architect Kenzo Tange, had, as its general theme 'Harmony and Progress for Mankind'. So that was the idea which Fleischmann had to work with. He knew that the architects were averse to anything figurative. The spirit of the exhibition was conceived as creating patterns for the future, and figurative art had no part in that. The pavilion consisted of four white boxes, suspended on a frame and connected by walkways, and the water sculpture in front of it, if not figurative exactly, was reminiscent of a slightly twisting prow in layers of blue Perspex supported on a red column. Three years later another opportunity came to exhibit the water sculptures. Arthur Fleischmann in fact held a very substantial one man show of these in the Victoria Embankment Gardens near Charing Cross underground. It was sponsored by ICI who provided the Perspex and was part of the Westminster Festival of 1973.

|

|

|

Arthur Fleischmann, Harmony and Progresss (perspex) 1969, photographed at Expo '70 in Osaka, Japan.

|

|

|

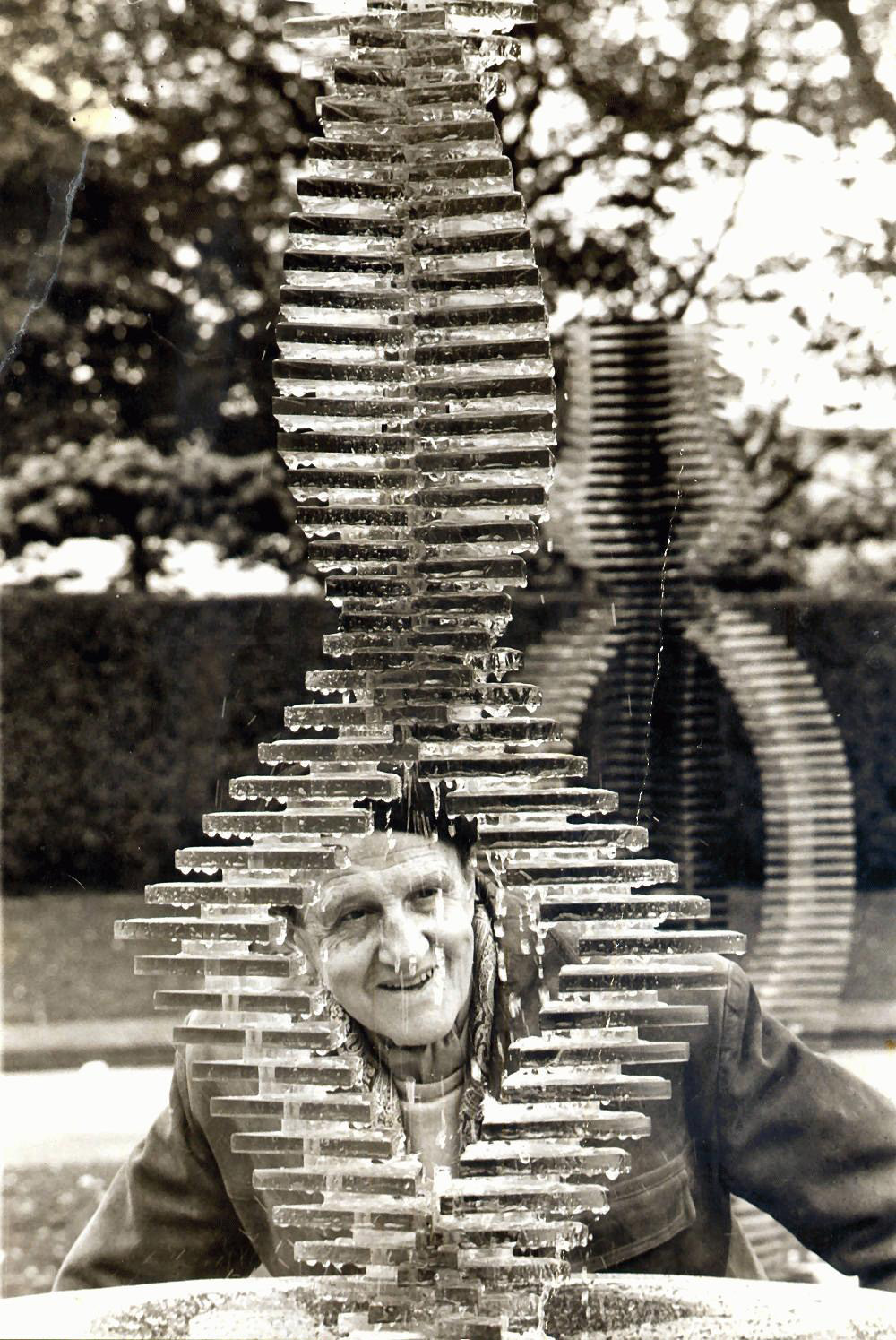

Exhibition of Arthur Fleischmann's Water Sculptures in the Victoria Embankment Gardens, Westminster Fetival 1973.

|

|

|

Exhibition of Arthur Fleischmann's Water Sculptures in the Victoria Embankment Gardens, Westminster Fetival 1973.

|

|

|

Professor Herkner, on his retirement from his Dublin post in 1969, made some of those expected remarks about the new experimentalism in art causing him to look back with regret to a time when the parameters of sculpture were a bit more clearly defined. His students nonetheless thought that he had managed to combine discipline and freedom in his courses at the college. Arthur Fleischmann in the meantime was making these practical demonstrations of his freedom, a quite remarkable example of self-reinvention in a man already in his mid-seventies

|

|

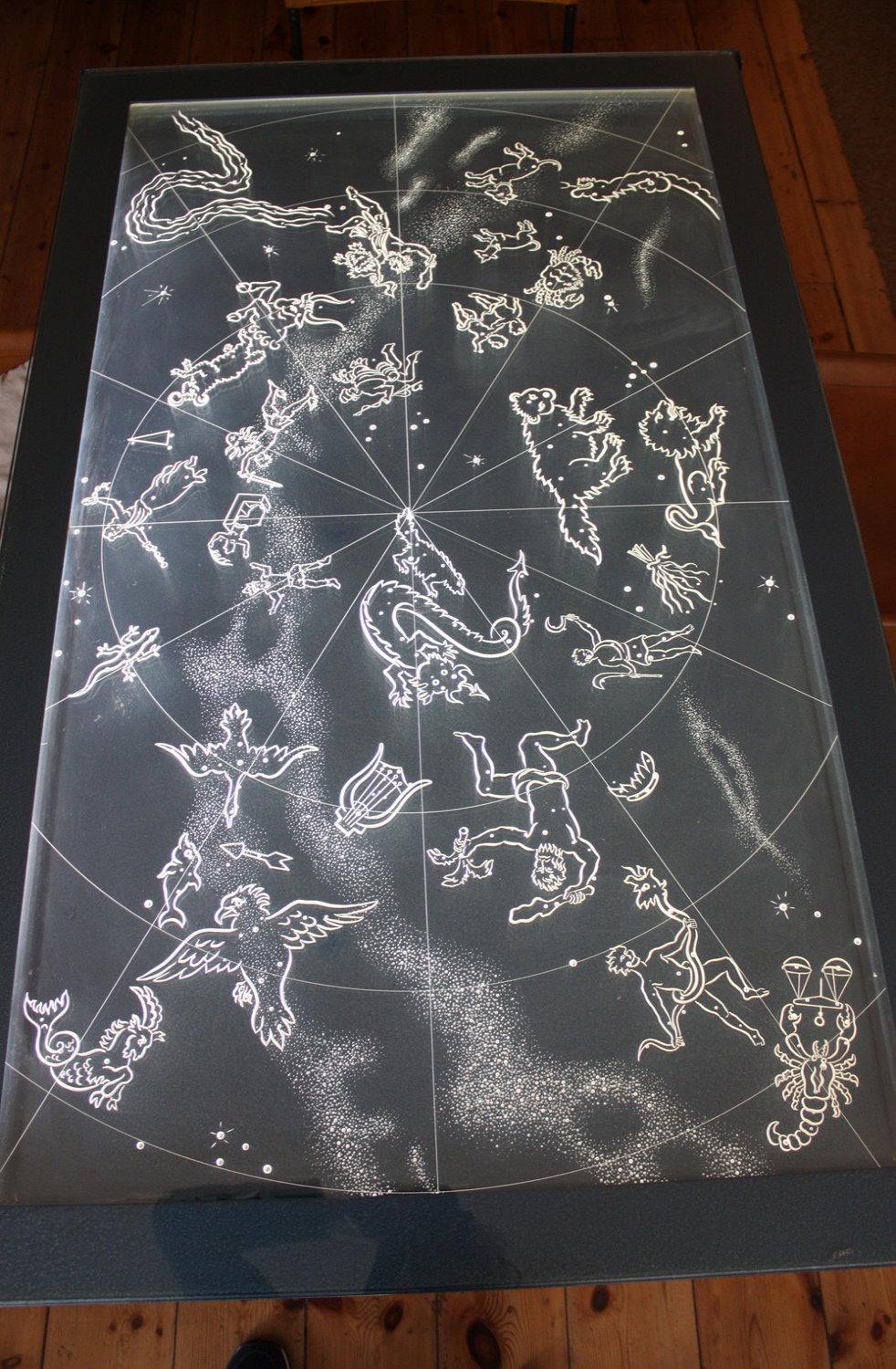

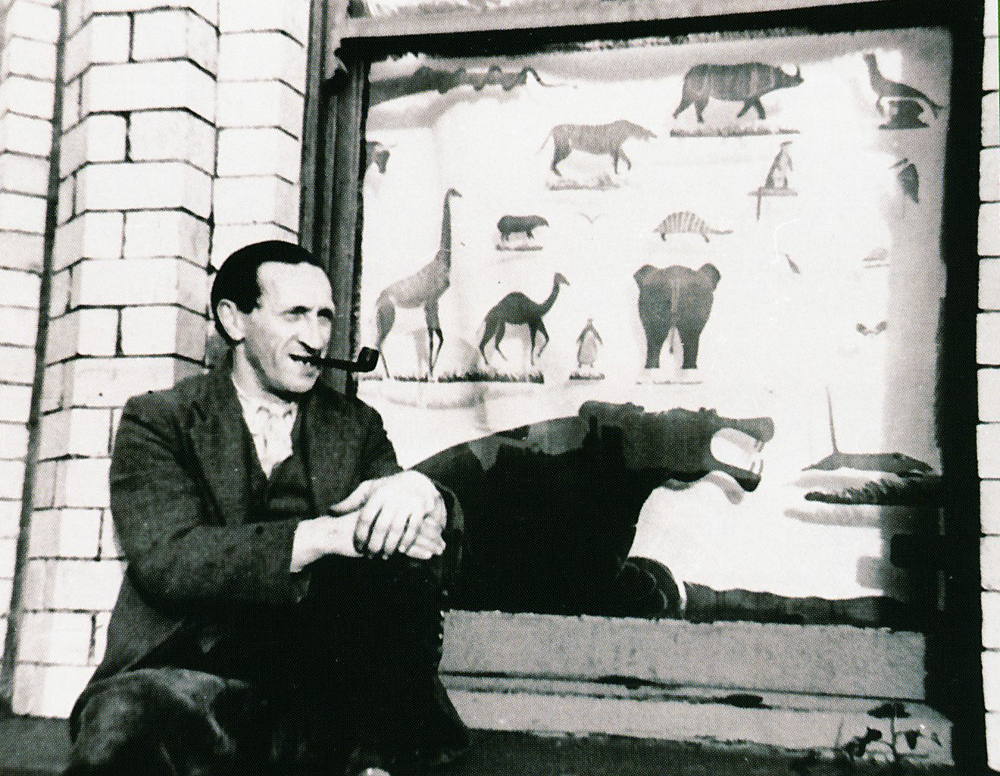

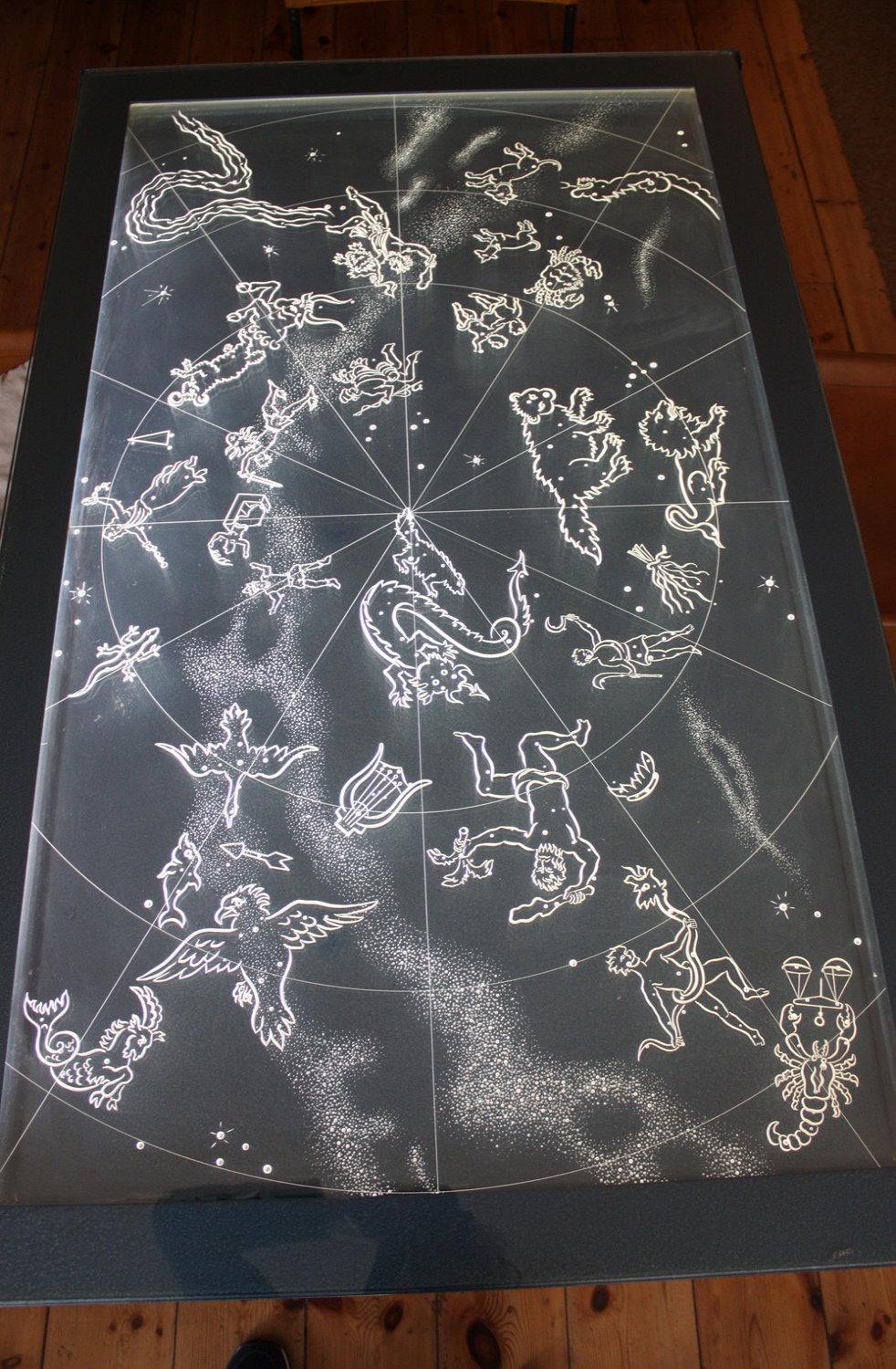

As an anecdotal epilogue, I would like to throw in a conjecture which some may consider far-fetched, but which highlights what I find to be one of Arthur Fleischmann's most attractive characteristics as an artist; his ability to tell tales, biblical or mythological, in a visual form which is explicit and decorative at the same time. One particular area in which he put this into practice, suggests to me also that he was not unaware of the hardships experienced by the Isle of Man internees, or of the ways they had found to keep their spirits up. The historian of the Hutchinson Square Camp, Klaus Hinrichsen, tells of the air-raid precautions taken at the camp, which required that the windows be painted blue and the light bulbs red. It was, people remembered, like living in an aquarium by day and in a brothel by night. The response of the internees was to get to work with various implements, and to scrape images on the windows, which might be mythological, biblical, or still-life. The various boarding-houses then came to be known by the subjects on their windows rather than by their street numbers. From the mid-fifties Arthur Fleischmann created a number of table tops in engraved Perspex, one of which became his own dining-room table. This is back-lit against a blue-grey ground, its subject the Signs of the Zodiac. To me it irresistibly recalls the Hutchinson Square windows as described by Hinrichsen. Unfortunately their actual appearance is recorded only in one surviving image. This is the window created by a man known to his fellow internees as 'Blick', an animal trainer by profession, rather than an artist, whose window looks to have been rather a naive affair. Could it be that Fleischmann, having heard from Charoux about the antics at the camp, was giving these windows a more durable form?

|

|

|

Mr Neunzer, known as 'Blick' with his Animal Window, In Hutchinson Square Camp, Douglas, Isle of Man, c.1940.

|

|

|

Arthur Fleischmann, perspex table top with Signs of the Zodiac, 1953.

|

|

|

Thank you very much.

|

|

|